This piece by Reggie Pawle first appeared on the Little Bangkok Sangha website, Bangkok, Thailand (11 July, 2020) and is representative of Reggie’s current interests.

******************

What do you say to university students who are depressed and don’t see much reason for continuing to live? For some time now students at the university that I work at have said to me that when they imagine themselves being my age (70), they see both society (due to pensions disappearing and governments being swallowed by debt) and the earth (due to environmental conditions) being unlivable. In their own experience they often have encountered social problems, like bullying and cyber-aggression. Now, with nature for now seemingly outsmarting modern medicine with the appearance of the corona virus, they feel their health future may also be affected. Many young people tell me their depression has become more pervasive.

From a Zen point of view, what can you say to these young people?

Many years ago I asked my Zen teacher, Sekkei Harada, what I should say to a group that invited me to introduce Zen to them. He said speak about the Three Marks. These are three aspects that all life has: impermanence (not fixed, transient), suffering or discontent, and no self. As these three are a part of all life, how you handle them is what is important. There are many other givens in life, but Zen focuses on these three. Why? Because how you handle these three will determine the quality of your life.

This corona virus has thrust human beings into unprecedented uncertainty, thereby bringing into focus the first of these three: the impermanence of life.

This means that life is a process that is forever changing and we have to be able to live in harmony with this condition.

Human bodies are built according to impermanence. One basic Buddhist teaching is the Four Kinds of Sufferings, which is that all of us are born and will age, get sick, and die. All of us are going through the human life cycle. The grossness with which this is depicted at some Buddhist temples in Asia shocks my Western sensibility. This photo was taken at Wat Damrey Sar Temple in Battambang, Cambodia:

Hopefully the reality of our death is not as gross as is depicted here, but nevertheless, the reality is that nobody can avoid these changes.

So I say to university students that each of us needs to accept our personal life cycle and the personal difficulties that come with it. We can make our lives better, but difficulties will occur in our lives.

Psychologically there are many examples of how we are built according to impermanence. One example is that we can’t see the future, no matter how hard we try. We don’t know who we’re going to meet tomorrow. Not knowing what is going to happen is a condition people don’t like, so they have tried all kinds of strategies to try to know their future. One common tendency is to focus on threats to their survival (google “negativity bias”) and then live adapting to this negative view of the future.

I advise young people, don’t get stuck on your depression. Remain open, to the bad and to the good. Don’t let your depression become your lens for your life.

Another way of being built according to impermanence is that our perceptual ability is limited. Even in this moment there are many things you can’t perceive. For example, the dogs at luggage carousels in airports can smell drugs in luggage, but

humans cannot. Therefore I recommend to my students that they recognize what they can and cannot understand, what they can and cannot do. It will help them understand their limits and have a healthy view of themselves.

The second mark is that all life is marked by suffering or discontent. No matter how hard you try, unpleasant things are going to happen. Our life cycle is not

only suffering or discontent, but it always includes these aspects. Suffering and discontent are two common ways that dukkha (the Pali word that according to the Buddhist tradition the Buddha used for this second mark of life) is translated.

There are very rare people who are born without the sense of pain. They usually die in their teens. This is because no matter how much others tell them behaviors like walking on a broken leg are unhealthy, they don’t understand as they don’t have the subjective experience of pain (see The Gift of Pain, by Brand and Yancey).

Pain appears because something is not right. What is important is how we handle pain. With pain comes an urge to avoid it. This is natural – you are not supposed to like pain! However, it is very easy to misunderstand this avoidance urge. If a person only avoids the pain, then they may never fix what causes the pain to appear. A person needs to develop the ability to stay with the pain, to accept it, and then to use the not liking the pain to motivate oneself to inquire into the source of it. Then, if a way to make things better is found, do that and the pain will lessen or maybe go away.

One example is people who have social anxiety. If they behave according to their anxiety urge, they will avoid social situations. However, they then will feel lonely, which will only aggravate their problem. What they need to do is tolerate their anxiety when in social situations and find ways to enter into relationships.

Buddhism asserts that we need to see reality as it is, including its suffering and discontent. Buddhism then articulates a way to end the suffering / discontent that human beings struggle with so greatly. This is elucidated in the Four Noble Truths. The essence of the Four Noble Truths is that if we deeply engage Buddhist practices, peace of mind is possible even in the midst of our suffering/discontent.

We need to commit ourselves to realizing this. We need to both accept our suffering/discontent as well as be committed to alleviating suffering/discontent as much as we can, both within ourselves and in the world. This is not just a Buddhist challenge. This is a human challenge. Viktor Frankl, who survived 3 ½ years in Nazi concentration camps (Man’s Search for Meaning), is an example of this in the Western Jewish tradition.

This is another bit of advice to young people who see only darkness around themselves. While you need to accept your suffering and discontent as a part of life, it does not have to be a part that runs your life. Rather, listen to the message it is trying to tell you. Whenever is possible, do what can be done to alleviate pain. Whatever pain you cannot alleviate you need to accept. If you handle your suffering/discontent in a healthy way, then you will be able to work with the pain in yourself and others and make whatever the situation is better.

And then there is the third mark of life, no self. This is the most difficult mark of the Three Marks to talk about. So many masters have tried and failed, simply because words cannot describe it. No self is the realization of the indescribable, often referred to in Zen as emptiness. One way of describing the purpose of Zen practice is to realize “no self”. What follows is, with the assistance of several people, my own attempt to explicate no self.

The term “no self”, which is also referred to as not self and non self, is about self – your self, “I”. To really understand no self you need to focus on your self, on I. No self is about you and how you live.

One way to understand no self is in terms of what your self is and what your self isn’t. No self points to the absence of the usual self. What we commonly refer to as our self is, in fact, an on-going series of experiences, all of which fall into what the Buddha referred to as the five skandhas: form, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness. The self we experience ourselves as being is comprised of these elements and they condition how we think, feel, perceive, behave, etc. However, all of these are impermanent. Their true nature is that they are forever shifting and beyond our control. When we find this difficult to accept, Zen says that we respond to impermanence in three basic ways: we try to hold on to that which we find pleasant, we are indifferent to that which we don’t care about, and we reject and/or avoid that which we find unpleasant. These are all ways of trying to control the flux of nature, which only results in suffering. Life cannot be bent to our will.

It may seem strange, but when we experience without our usual responses of grasping, indifference, and avoiding, we can let experience be as it is in each moment. We may still not like it, but we can accept it as it is and then mysteriously, somehow, peace arises. Joshu Sasaki, a Zen monk, wrote in his book (Buddha is the Center of Gravity), “You have a very bad habit of only making your home inside of whatever you like. That’s why you feel you are not free.” When we can make our home in whatever circumstances arise in life, then we can be at peace. In Buddhist language, this is because form truly is formless, or, delusion is enlightenment.

Our reaction to impermanence is motivated by our egoistic grasping, attachment, and self-concern. This clinging to our ego-self can foster mind states referred to in Zen as defilements (pollutants). These are mental factors that disturb the natural peace of mind that everybody has. The basic mental defilements in Zen are said to be greed, anger, ignorance, pride, doubt, and false views. These six are subdivided into 102 more defilements, resulting in a total of 108 mental defilements. An integral part of a person’s usual self is some combination of some of these defilements. Letting go of one’s own defilements is basic to realizing no self.

What is the realization of “no self”? Sekkei Harada said that the realization of no self is not an experience. If it is not an experience, how can it be described? Saying what is “no self” can easily result in misunderstandings. Thus Zen usually speaks in terms of what it is not, with terms like emptiness. Emptiness refers to being empty of the created self, with all of its delusory ideas, feelings, and awareness. However, being empty of one’s created self is not a condition or a mental state of nihilism. Pointing to emptiness as indescribable, Sekkei Harada said to me once, “It is not that it is a literal void. It is just that it cannot be perceived.” As referred to earlier, our minds have perceptual limits. No self cannot be perceived with the perceptual abilities that mind has.

Keido Fukushima, a Zen monk, did describe in an interview a positive view of no self. He said, “It’s not just a negative meaning. It means that there is no ego. There is no self-nature. All is empty of self and yet you can say by cutting off the ego there’s a way in which you’re living without ego, it’s actually a very positive thing. It’s a way of living without ego.”

This way of living is one in which a person lets go of their sense of self as a fixed identity or an existent. Then their self becomes more like a function or an activity that is constantly in flux. To accept with grace the many changes we encounter and to not take them so personally. Rather than being a person who lives trying to make their self into something it isn’t by attempting (and failing) to control life according to their desires, fears, delusions, etc., living life as non-self would mean living in a way that is responsive to the ever-changing and interconnected nature of life.

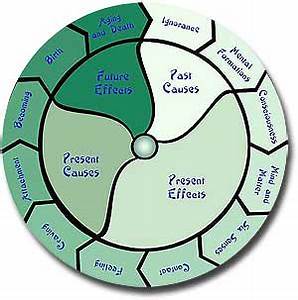

Living in this way includes exercising our will. The Buddha only realized his true nature because he was determined. He had great desire to be free of his suffering. The ever-changing and interconnected nature of life occurs, according to Buddhism, by causality, the interaction of cause and effect. Everything that happens is a result of one or a few main causes and many contributory causes. Each occurrence then becomes a cause for the next effect. Living no self means living as a very sophisticated, interconnected system with many integrated functions, without the common assumption of a controlling center like the ego-self. We need to include our will in this web of causation. We need to be active while at the same time accepting our condition as it is and having peace of mind. Sodo Yasunaga, a Zen monk, said to me in an interview that a person has to do their best, but the realization of no self occurs through conditions and circumstances outside a person. He said it is strange, but “your active effort is in vain. However, you have to do it.” Making effort is a natural function of being a human being. Finally, however, it one’s self, I, the source of one’s thoughts, emotions, and will, that is transformed.

People thought that modern medicine had eliminated plagues and pandemics and they didn’t have to pay attention to such things anymore. However, all life is still part of nature and subject to how nature works. If people live out of harmony with nature, then eventually there will be effects of this way of living.

Modern medicine has been used by society in a way that supports the illusion that living in disregard to nature is ok. When people go to see a modern doctor for some ailment, they have the choice to ignore any advice they may receive. All they must do is passively to receive the treatment and then, if it is successful, they can choose to continue to live as they did before. I knew a guy in the U.S. who had a serious heart condition. He also loved to eat steaks multiple times a week. His doctor told him that

if he wanted to live, he either had to stop eating steak or he had to have heart bypass surgery. He didn’t want to let go of his desire to often eat steaks, so rather than bringing his desires into harmony with his condition, he chose the surgery. Maybe a steak once every couple months or so would have been ok, but he couldn’t accept that. Sekkei Harada once said to me, “It is not your desires that are the problem. It is the one who is desiring that is the problem.”

Zen practice focuses on this one, which is your self, I. Who am I in truth? This is a question that every Zen student must resolve. To do so requires deep study of who am I. Dogen, the founder of the Soto sect of Zen in Japan, wrote, “The Way of the Buddha is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the ego-self.” A person must let go of living through their delusions. Rather than taking a pill or having surgery, this requires effort and changes of a person that are not so easy. To realize no self Zen practice is highly recommended.

So my advice to young people is first to take a good look at themselves, to deeply examine the ground of their self on which they stand. Make the effort, do whatever you can to realize a non-deluded self. And when you find ways that you are interfering with the interactive forces of nature, let go of your interfering, and be in the natural harmony.

Zen has these three complementary parts – making effort, letting go, and being. This is the basis of my advice to young people. I say to them, do whatever you can to help yourself and help the world, then let go, and be at peace.

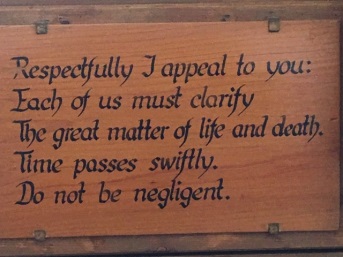

There is one more very important concern that needs to be addressed when faced with this corona virus – it threatens people with death in a way that human beings haven’t felt in a long time. Even if you live in harmony with nature, you still will get old, sick, and die. As my great aunt used to say to me in her British accent, “Getting old is a dreadful nuisance”. In the entrance area of the meditation hall of almost all Zen monasteries in Japan hangs a sign, written in Chinese characters. At the monastery I have practiced at for many years next to this sign hangs a sign with an English translation:

Death is the greatest impermanence, suffering / discontent, and lack of self in life. If you can resolve the great matter of life and death, then you also resolve impermanence, suffering / discontent, and self. Then you will be at peace.

One word about trying to resolve this great matter. Don’t approach this in a linear way, as in going from not knowing to knowing. Rather, it is in the trying to resolve this itself that the resolution will appear. Keiji Nishitani, a Japanese Zen philosopher, expressed this as, “Life is transformed through trying to resolve unresolvable questions”.

The corona virus brings this great matter into clear focus. It is up to all of us to make the effort to clarify life and death. This is the heart of Zen and is the biggest challenge that the corona virus presents to all of us.

****************

Postscript

I dedicate this article to my teacher, Sekkei Harada, who died recently on June 20, 2020, about sunset time. He was 93. When you find a true teacher, he (she) is irreplaceable. I miss him very much.

For more about Reggie Pawle, see here.

Recent Comments