July in Kyoto means the Gion Festival, the city’s premier event which stretches over the whole month and provides tourists with an array of glittering photo-ops. The piece below is an excerpt from “Kyoto Souvenir,” a book by Fernando Torres still in the preliminary stages which tells of buying a forsaken house in Higashiyama. (He describes it as “Under the Tuscan Sun,” if it had taken place in Japan and was written by a Mexican-American from Las Vegas.) (JD)

July in Kyoto means the Gion Festival, the city’s premier event which stretches over the whole month and provides tourists with an array of glittering photo-ops. The piece below is an excerpt from “Kyoto Souvenir,” a book by Fernando Torres still in the preliminary stages which tells of buying a forsaken house in Higashiyama. (He describes it as “Under the Tuscan Sun,” if it had taken place in Japan and was written by a Mexican-American from Las Vegas.) (JD)

Kyoto in July is where I learned the vocabulary for “what am I doing here instead of someplace cooler,” or “mushi-atsui,” as is said in the local vernacular. In Las Vegas, we don’t actually have humidity. Months go by with nary a cloud in the sky. Like a character from one of my fantasy novels, I find myself able to project small bolts of lighting from my fingers, much to the detriment of Winston, our British Shorthair. In Kyoto, there are no such problems with static electricity as the humidity is as thick as the purin I eat with my lunch. Were this not a country of “mildly air-conditioned” train cars, it might not feel like a chapter in Dante’s Inferno. People in Japan seem to enjoy complaining about the heat as much as folks in other countries enjoy talking about sports or politics. In an unexpected moment of wisdom, we decided to become the first owners in our house’s 120-year history to install air-conditioning. Since I never met any of the previous occupants, one can only assume that they melted and were absorbed into the soil beneath the foundation. As I luxuriate beneath the vents, like a Christmas ham, I don’t even care that Kansai Electric raised the rates after the earthquake. One of the advantages of being an adult is the ability to run your air-conditioner with only your pocketbook to object. It could scream for all I care, and I would just smother my wallet in the blanket of humidity that covers the city. Every year, I swear that I will avoid Japan during the sweltering months of summer, for someplace more comfortable like Las Vegas or Hell. Drawn by some home improvement project or festival, however, I continuously find myself in the ancient capital fanning myself like a character in a jidaigeki (時代劇). There is a heightened sense of community in communal suffering. I suppose seeing the sweat pouring down someone’s forehead has the effect of humanizing them.

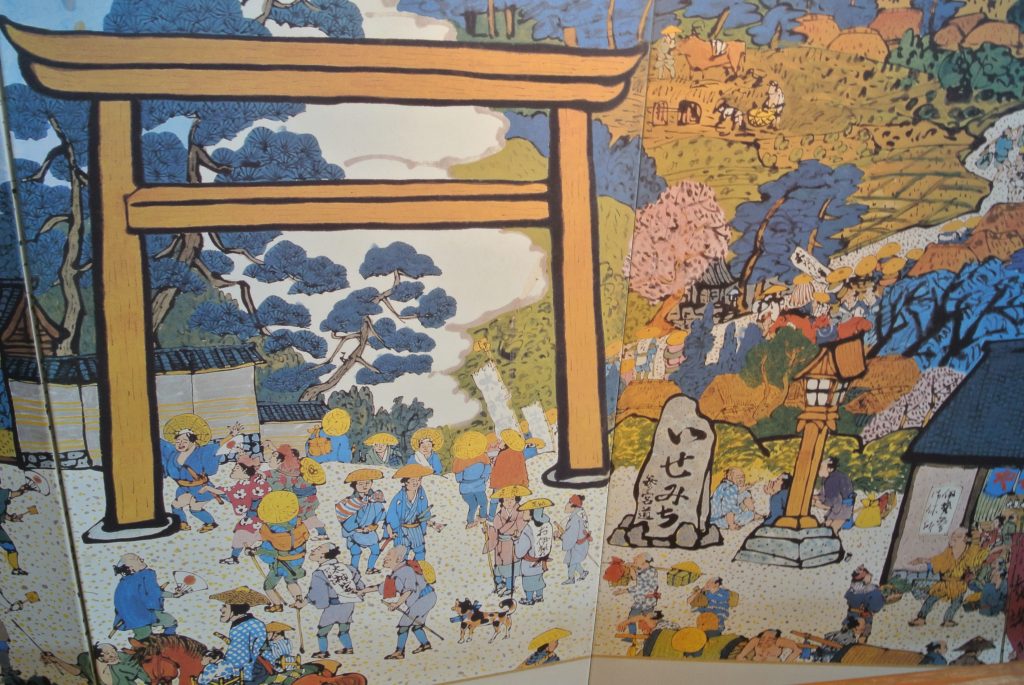

In a city of festivals, one towers above them all, quite literally. Gion Festival is held every July because apparently October was already booked. I believe the same meteorologists who create the cherry blossom forecast are the ones who determined the absolute hottest time of the year in which to hold a matsuri and the rest is history. While its origins are in a ritual to prevent disasters (御霊会), I am reasonably sure I will spontaneously combust from the heat. Thirty-two movable museums, some twenty-five meters tall, are pulled with great hemp ropes down the streets of the city as has been done for over a thousand years. The nine hoko floats are not able to be steered, but by dousing bamboo strips laid under the wheels with water, the fifty or so men can turn them in the appropriate direction. I have a chance to view these venerable skyscrapers at the Yoi-yama street party. Shijo-dori is completely closed to traffic. I experience a sense of thrill walking down the middle of the street, where I usually can only ride in green city buses or in the back of red and black taxi cabs. It seems as if all of Japan has descended upon Kyoto to view the parade floats and eat chimaki cakes wrapped in bamboo. Some of the neighborhood houses display their heirlooms which gives me a chance to look into machiya that would normally be closed to my prying eyes.

For those looking for additional culture, long lines are available in front of the food stalls. This is to uphold the Japanese pastime of standing for unreasonable periods of time with an ungodly number of your fellow citizens. I knew I had become a local when I got in a line at a food hall without any idea of what they were actually selling. The person in front of me didn’t know either. The lukewarm yakisoba I’m handed is brought up to the appropriate temperature by merely sharing the heat enjoyed by the thousands of us packed like unagi in a bento box. Still, there is something about festival food that is irresistible. Perhaps it is the idea of a reward at the end of the line.

The day of the parade, the Yamaboko Junko, my wife and I decide to wear our yukatas, but perhaps a more appropriate outfit would be an air-conditioned space suit. We find a place across from where several local maikos are giving gifts to the participants as they pass. The juxtaposition they create, with the conbini store behind them, is a fitting symbol for the age-old festival in the modern era. One of the gentlemen drops the gift they have handed him, which elicits polite laughter from the maikos eager to maintain the harmony (和). Paid seating is available, but I’d rather use the 3000 yen towards keeping my house as cold as an icebox. Especially, when the reward at the end of this line is a thousand years of history with friends and neighbors in the city that I love.

For a self-introduction by Fernando Torres, please click here. There is also a professionally produced 4k video shot by him last July, which is just seven minutes long and has rare close-up shots of festival scenes and Kyoto highlights, all set to atmospheric music and visually appealing.

Oftentimes otherworldly happenings can more precisely explain everyday events in our world. In Lafcadio Hearn’s “The Screen Maiden” an exquisite painting of a beautiful young girl becomes the betrothed of a young man. A most intriguing read indeed, the story seems to hint at three critical aspects of love: patience, humility, and reciprocity.

Oftentimes otherworldly happenings can more precisely explain everyday events in our world. In Lafcadio Hearn’s “The Screen Maiden” an exquisite painting of a beautiful young girl becomes the betrothed of a young man. A most intriguing read indeed, the story seems to hint at three critical aspects of love: patience, humility, and reciprocity.

The summer that Japan hosted the World Cup was one of the highlights of my many years there. By day I was hitchhiking the 33 temples of the Kansai Kannon pilgrimage, while at night I’d return to a city somewhere to watch a match. I’d choose bars or pubs that had a connection to one of the teams on the pitch, and the energy of the fans could barely be contained within the four thin walls of the place.

The summer that Japan hosted the World Cup was one of the highlights of my many years there. By day I was hitchhiking the 33 temples of the Kansai Kannon pilgrimage, while at night I’d return to a city somewhere to watch a match. I’d choose bars or pubs that had a connection to one of the teams on the pitch, and the energy of the fans could barely be contained within the four thin walls of the place.

Kirsty Kawano: Interview

Kirsty Kawano: Interview

Leading Shinto scholar

Leading Shinto scholar

Mike Freiling

Mike Freiling

Recent Comments