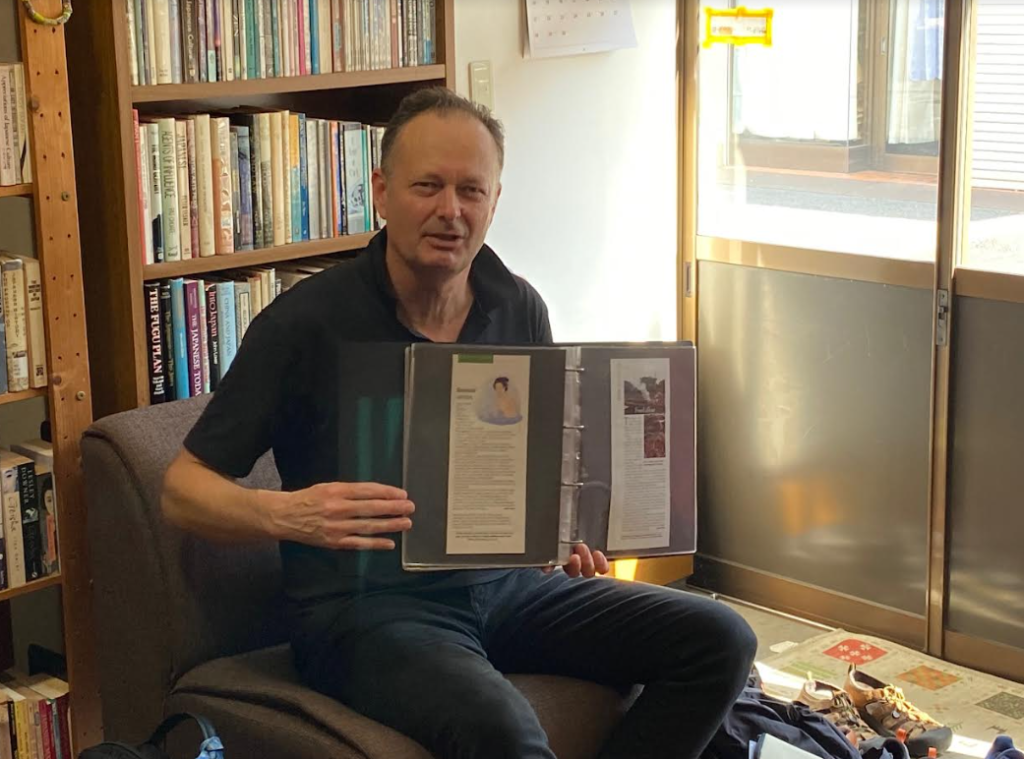

by Sara Ackerman Aoyama

Sara Ackerman Aoyama first went to Japan in August, 1976 as a member of the Associated Kyoto Program (AKP). It gave her just a bare taste of Kyoto and after she graduated from college, she returned to Kyoto in the summer of 1978 with no plans other than conquering the Japanese language.

In the late 1970s you could often find me at a counterculture hangout called Kyoto Demachi Kokusai Kōryū Center. In English it was grandly translated as the Demachi International Exchange Center.

Much of my time at the center was spent doing small tasks for Professor Nakao Hajime and the antinuclear power movement. The 1979 accident at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania had alarmed him and other activists. I wasn’t calling myself an activist, but there was plenty of opportunity for me to get involved, be it translation or transcriptions of English interviews. I kept myself busy and gained an impressive new vocabulary in Japanese. I’d draw diagrams of nuclear power plants trying to understand terminology in both English and Japanese. In some ways, the Japanese was easier because the kanji themselves would give a clue to the meaning.

But it wasn’t always activism and there were times for conversation, meals, and relationships. A steady stream of visitors would come in from Tokyo or even further away. The core group was almost always there for dinner. I’d sit there trying to keep up with the conversation but it was so rapid that much of it would get by me. I had to be content to catch what I could.

Akira Matsumoto was a married man with children that I’d met previously at Honyarado. He was a carpenter and had built the small darkroom down the hall from the kitchen. He was a regular at the center like I was and he’d drop by just to hang out at the end of his work day or between jobs. He did not seem to have a regular schedule and it didn’t seem like he ever ate dinner at his own home. He took an interest in me and was often amused at my bumbling attempts to fit in. He never hesitated to give me language corrections. I lived for those moments, desperately wanting to fit in and understand more of the conversation happening around me.

You see, at that time, most Japanese would hear me speak Japanese and politely or gushingly comment on how well I spoke. That was practically de rigueur:

“Nihongo wa jōzu desu ne!”

(How many thousands of times have I been told this, I wonder, even today.) But my very first Japanese teacher at the University of Kansas, Professor Richard Spear, had covered this scenario. He was the kind of teacher who taught language hand in hand with culture. He instructed all of us that there was only one conceivable response to this:

“Iie, mada heta desu.”

That meant, “Oh, no. I still speak very poorly.”

I wasn’t entirely convinced and put forth a number of challenges.

“What if your Japanese has gotten really good, though?”

“Same answer,” he replied. Hmmmm. I went a little further.

“What if you’ve lived in Japan for ten years and can even read a newspaper?”

“Yes. Same answer.”

And my last push was, “What if you end up living in Japan for over thirty years and you’re really really really fluent?”

He thought about it and gave me this:

“Mada sukoshi shika hanasemasen.”

(“Oh, I still only speak just a little bit of the language.”)

And as the years passed, I realized what an important lesson this was. If someone tells you your Japanese is very good and you respond saying “thank you” then you’ve just proved that you don’t really get Japan at all.

Back to Akira.

Akira really wanted to get me naked. Since the center was originally a residential home, it had a Japanese bath that got heated each night. Akira regularly issued an invitation to me to take a bath, preferably with him. I ignored those invitations. The public bath was just fine for me and I was living nearby in Hyakumanben and had my choice of a few of them. From Akira’s point of view, he’d invested considerable time in schooling me in Japanese language and relationships. To my chagrin, he’d even once introduced me to his daughters as “your future mother” right in front of his smiling wife. This was after he’d had surgery and I’d self-consciously made a visit to the hospital with a colorful bouquet of flowers for him. He was much amused and pointedly remarked to his wife (also amused) that he’d never ever gotten flowers before.

Fruit, dammit, I thought to myself, as I looked around the room. Apparently that’s what I should have brought, but it was too late. His daughters were eyeing me with interest and I wanted to melt into the ground.

Inviting me to bathe with him was more of a challenge to himself and a way to tease me. He’d pegged me as an uptight wanna-be cool girl. I got used to his teasing and mostly brushed him off. I valued our friendship, though, since he’d patiently correct my Japanese and throw in a few examples of how to use words I was struggling with. So when he started bugging me to take a bath with him, I’d just roll my eyes and put up with it. Until one night a year or so later when I was visiting after I’d moved to Tokyo.

After I moved to Tokyo, I’d often go “home” to Kyoto and stay for a few days or longer. When I did, I would stay at the center. There was always room for overnight guests and I’d just pull out a weathered futon and make myself at home. For the first time, I began using the bath at the Center. It was right off the roomy kitchen.

So one spring day, I was visiting as usual and after dinner I went in to take my bath. Akira was in the kitchen washing up the dinner dishes. Everyone else had wandered off.

Suddenly there was a frantic knocking at the door of the bath, and Akira called out to me to check something with the gas. I rolled my eyes. I knew what he was up to and told him to go away. He became even more frantic and started talking about the gas valve again. Something about the setting that he wanted me to check.

Back then the gas valves were every American’s nightmare. We hadn’t grown up with gas valves near our water outlets. We knew that the very first tremor of an earthquake meant that you had to immediately turn off the gas valve. My homestay mother wouldn’t even let me use hot water because she feared I’d make a mistake with the valve. Gas was scary and dangerous. You could start a fire, blow up a kitchen, or even sicken a whole household.

Meanwhile, Akira was adamant. I needed to check the gas valve in the bath and turn it a certain direction or make sure something was working properly. I started to get a little nervous. I was already submerged in the bath. Could I handle this situation? Did I really want to cause an explosion? Or was Akira kidding me? The house was a very old wooden structure. I got more nervous. Akira was demanding that I unlock the door and let him in if I didn’t understand his instructions.

I capitulated. It seemed too risky to doubt him any further. I rose from the bath, quickly unlocked the door and scrambled back into the bathtub. And Akira burst into the room.

By that time I was shrieking at him to fix the gas situation, but Akira himself was quickly ripping his clothes off and climbing into the tub with me, sending the hot water splashing. Laughing of course. I’d been had.

It was like bathing with a sister. Nothing untoward at all and he was just happy to be in the bath with me and happy to have completely fooled me. I rolled my eyes again and admitted he’d pulled one over on me successfully.

**************

Postscript: In 2016, when I visited Kyoto for the first time in many years, I asked Nakao-san about Akira. Sadly, he told me that Akira had passed away a few years before that. So, I told the professor the story of how Akira got into the bath with me at the Center. He laughed uproariously and thought it was a great tale. And it remains now as a warm memory. Oh, those gas valves and the havoc they wrought

***************

For Sara’s previous posting about photographer, Kai Fusayoshi, click here.

***************

About the Center1

In the early 1970s, Friends World College established the East Asia Center in Kyoto under the direction of Nicola Geiger, who had traveled to Japan with her husband and spent time previously in Hiroshima. The East Asia Center was housed in the old home of a Kyoto University professor who had since moved to Nara and had made it available to rent. Somewhere around 1974, Jack Hasegawa took over the leadership of the center and around 1978, he moved the East Asia Center to a location close to Tōji in Minami-ku. Nicola, who was still living in Kyoto, moved into the first floor of the rambling old home, but as she was unable to afford the rent on her own, she reached out to Nakao Hajime to see what could be done. By that time, America had withdrawn from Viet Nam and the counterculture movement shifted directions towards democracy movements in South Korea, the antinuclear power movement etc. To support these movements and publish flyers and newsletters an office was set up at this center, which was located in Tadekura-cho near Shimogamo Shrine and not at all far from Honyarado. The home was newly christened as the Demachi Kokusai Kōryū Center and though it never lived up to the rather ambitious name, it became a drop-in center for activists and any number of residents as needed.

The Demachi Kokusai Kōryū Center was not destined to last very long and the lease ran out during the summer of 1983 effectively bringing the center to a close.

1 Nakao, H. (2024) Based on a personal email to Sara Aoyama January 6, 2024, and translated from the original Japanese

Recent Comments