by Richard Holmes

The view from the roof was always dynamic and inviting. I could see clearly in all directions, something odd for a big city that was supposed to be in perpetual haze.

I spent three years of my early youth on top of an eight-storey office building on Chancery Lane. This was just one of many pit stops or temporary perches I stayed at. My parents were caretakers. This meant that we led a very nomadic urban life. Despite the short time I lived there, it was to leave an indelible impression on me that would come back and prepare me well for the latter years of my life.

Chancery Lane was originally the thoroughfare for the London legal profession. It stretches from High Holborn all the way down to Fleet Street, home to the UK’s major newspapers and the Royal Courts of Justice. It dates back to the mid 12th century when the Knights Templar created New Street between their old headquarters in Holborn and their ‘New Temple.’ It was to become known as Chancery Lane by the early 15th century, named after the Court of Chancery.

(photo courtesy Londonist)

Chancery Lane also forms the western edge of the City of London which is also referred to simply as the City or the Square Mile as it is, well, just over a square mile in area.

Across the way from the building where I lived were the Silver Vaults, a collection of antique and silver shops dating back to the mid 19th century. It is home to about 30 retailers and offers the largest selection of fine antiques and silver in the world.

Of course, being a curious lad I ventured inside one day only to be greeted by a gruff voice, “Ooo the ‘ell are you?” I pointed across the way, “I live over there,” I replied. “You must be Arfur’s lad, then. You’re alright. Come on in.” I visited the shops quite frequently and got to know the owners as well as Bill the doorman.

(photo courtesy Tripadvisor)

The entire area is full of old historical buildings and inns of court such as Lincoln’s Inn Fields where judges and barristers have their offices.

During the week, the City was always alive and bustling with lawyers, barristers, bankers, writers, journalists, people of all trades but mostly professionals – all in some kind of flurry and hurry. Come weekend, the City was dead as a doornail. But, that’s when it would come alive for me. It turned into my own personal adventure playground. What else does a curious young lad with a thirst for adventure do but go out and explore?

Every turn on cobble-stoned streets led me to new avenues and adventures, new discoveries. On weekends, the map I drew in my mind’s eye grew. Nooks and crannies, cobblestones, stone pavements, cast iron railings, tree grilles, metal bollards, worn stone gargoyles on the sides of buildings, Victorian hand-lit street lamps, blue-enamel plaques denoting that a famous personage “lived here” all those years back, artfully carved stone window frames, vaulted stone roofs, and neatly laid brick chimneys were ingrained in my memory and became a part of my life.

I remember one particular church just off Fleet Street which opened its stone crypt to the general public from time to time. Right down in the belly of the church, they had excavated buildings and graves dating back to Roman London from around AD 50. In my youthful innocence, I imagined that everything up from there got younger.

With each weekend adventure, I was breathing and living history in the moment however insignificant the footprints I might have been leaving behind.

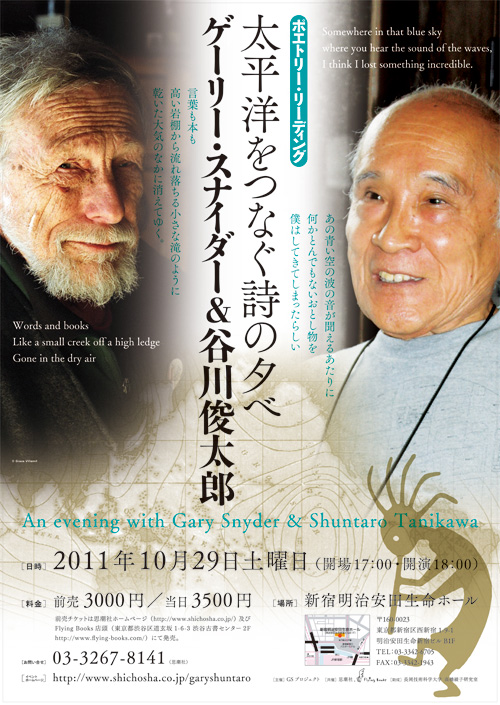

One favorite placed I loved to pass by was Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese. Noted for its literary associations, this pub is located in an unassuming alley just off Fleet Street and dates back to a similar establishment from 1538. As you can see from the sign outside [pic below], it was rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1666. This puts a lot of those “Since 1972” upstart logos you often see in shops and bars about town to shame. The only watering hole in Kyōto that comes close and has bragging rights is the Samboa Bar on Teramachi which was established in 1918 and is currently run by my mate Hiroshi.

I visited Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese about 30 years ago on a business trip back to London. I got chatting with the landlord and found out that if you crossed his palm with silver – “A pint will suffice, sir” – he would give you the keys to the wrought iron gate to the stairs next to the counter. Two flights down I found myself in the vaulted cellars of the basement which apparently dates back to a 13th-century Carmelite monastery. My boyhood curiosity had gotten the better of me and I was face to face with history yet again. The pints I had when I re-emerged from the cellar tasted that much better.

This picture of the pub’s frontage really does not do the establishment justice as when you venture inside and walk past the fireplace and an equally old oil painting hanging above to the main counter, you will immediately notice that you have stepped back in time. You will also see corridors going off in all directions like a maze into a set of other dimly lit rooms with their own bars. Yet, another gem of history to explore. It’s a huge pity that I didn’t have the chance (and the age) to savor the delights and have a few jars there as a young lad. Adult playgrounds, well, I suppose are for adults.

Talking of which, it is also rumored that one of the upper rooms was used as a brothel in the mid-18th century thanks to a stack of sexually explicit tiles that was found there. I have it on good authority that these tiles found a suitable home in the Museum of London.

(photo courtesy wikiwand.com)

When I started writing this piece, it struck me that I am quite comfortable and at home in Kyōto most probably because I am in some way subconsciously reliving those years of my early youth in the City. I’m a strong believer of fate and karma, the result of my actions whatever decisions I have consciously made. In this respect, one of my favorite Kanji characters is 縁 – connection, fate or destiny.

Was my eventual coming to Kyōto pre-ordained or completely accidental? Was Chancery Lane a training ground for my life here in the greater scheme of things? Was my learning Japanese at university a direct result of or a backlash against studying Latin and Greek – both dead languages – at grammar school?

I ought to add that the grammar school I attended dates back to 1594. Was history and the past always finding a welcoming recipient in me, or vice versa?

Whenever I go to a local shrine or temple, drop a few coins in the offertory box or light a candle for the health of my friends and family, or casually walk past a temple several hundred years old that just happens to be designated cultural history and catch the waft of some fragrant incense, I sense that I am re-enacting what I and others used to do out of habit every day of the week in Chancery Lane. Then, I see a Buddhist priest in his black livery and surplice over his shoulder riding off into the distance to visit his parishioners, locals sweeping up leaves in front of a Jizō (children’s guardian) statue and replacing old flower offerings with new ones, shopkeepers splashing water on the pavement in front of their premises, or priests in training down from Mt. Hiei walking around the neighborhood and chanting prayers, and I realize they’ve been doing this for centuries. Time-tested traditions handed down through the ages are alive and flourishing. To an outsider, they may seem arcane, but to those living here actions like these done day in and day out are taken-for-granted. They are an integral part of the Kyōto landscape, its DNA.

Any vestige of that gangly youth in his early teens has long vanished. That skinny wretch has filled out and now sports a slight paunch, well, maybe not so slightly.

When I turned 60, I had this realization that a new life was spreading out before me and that new opportunities were waiting for me. Older in body but still very young at heart, it was nice to re-discover that the youthful curiosity and spirit of adventure of my early days in Chancery Lane had not left me.

So, now that I have arrived and found the perfect perch here on Yoshida-yama Mountain – an ambitious misnomer for a bump on the landscape to the east of Kyōto University – I’ll be flying off from time to time to make the rounds of my new adventure playground. And, as all of my fellow WiK writers know, Kyōto is full of inviting alleyways like those of Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, nooks and crannies, and hidden treasures just waiting to be discovered.

********************

For Richard’s previous piece on ‘The Old Man’ and dementia, click here.

Recent Comments