by Sara Ackerman Aoyama

Introduction

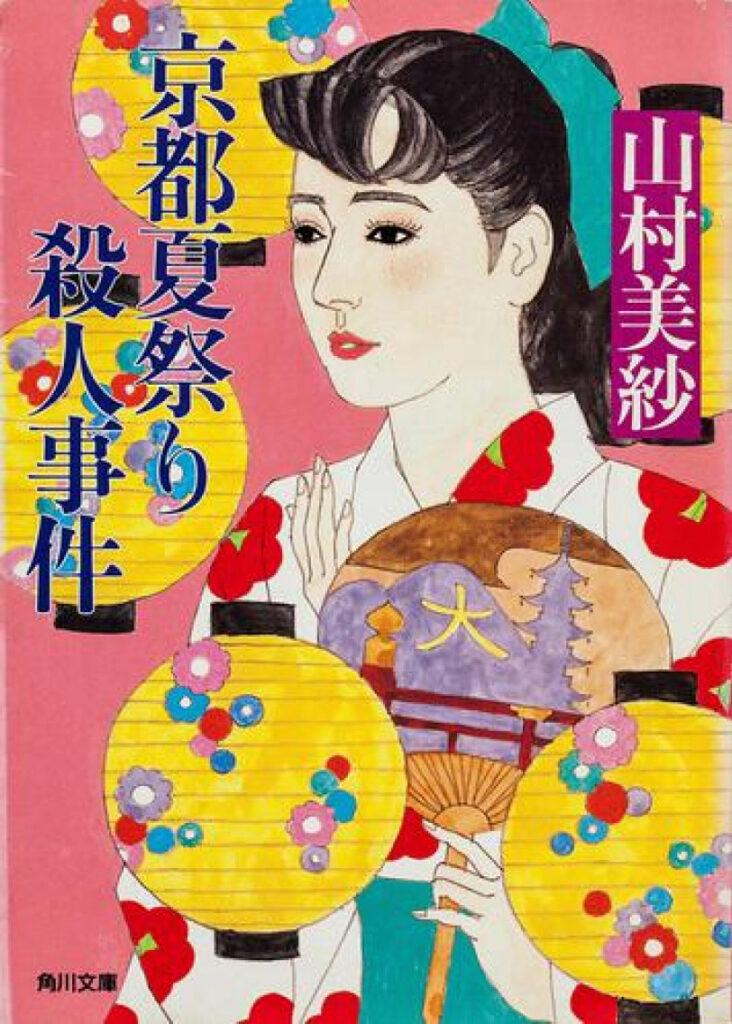

In this second entry in the series, I’m introducing a woman writer, Yamamura Misa. She is well known as a mystery writer and a very prolific one at that. Many of her books have been adapted for television mystery series and a few of them have also been made into video games. She has been translated into Chinese, Russian, French etc. but I was unable to find any of her books currently available in English. While many of her books are set in Kyoto, she has also set her mysteries in other parts of Japan, both near and far. Additionally, there are a few of her mysteries set overseas in such places as Paris and Guam.

Biography

Yamamura Misa (August 25, 1934 – September 5, 1996) was born in Kyoto City proper. During the war, her father served as a principal of a college in Korea, so she spent some time there as well. After graduating from college with a degree in Japanese Literature, she went on to become a junior high school teacher in

Fushimi. Upon marrying at the age of thirty, she retired from her teaching position. She took up writing a few years after that and quickly found success as both a novelist and a writer of screenplays and drama. But her mysteries were what she was most well known for and perhaps unique for the times, one of her favorite recurring characters was an American woman named Katherine who was the daughter of a fictional American vice president. The ‘Katherine’ novels were adapted for television quite frequently and the role has been played by both Japanese and Western actresses, the most recent being Charlotte Kate Fox, an American actress and singer from New Mexico, who also appeared in the NHK morning drama, Massan.

Yamamura was also well qualified in Japanese arts such as flower arranging, tea ceremony and traditional dance, and this enabled her to incorporate traditional arts into her Kyoto mysteries. She passed away of heart failure, leaving behind her daughter, Momiji, an actress. In her will she requested that Momiji be given a role in any future dramatizations of her work.

I was drawn to Yamamura Misa’s works purely for her Kyoto settings, but I wondered if I could really read a mystery in Japanese and be able to follow the plot lines and pick up on the clues. Yamamura is a clever writer and her success is due to her so-called tricks that she employs when she writes. But with an American character, I found it easy to relate to her adventures and though it may be impossible for a budding Japanese language student to pick up on every clue, they are quite readable; it should be quite easy to find a copy of many of her books in a used bookstore. Should you happen to catch an airing of one of her dramas or find one on the internet, that will aid you in understanding her storytelling style. And finally, a few of her works have also been published as manga.

It is very difficult to find photos of this author. And she seems to have been somewhat of a mystery herself. Despite being a very popular author of her time, there is little written about her and it seems that this is how she wanted it to be. Although the Wikipedia articles are written decisively, it is possible that even her real age at death is unknown. Seeking to remedy this, a more contemporary Kyoto author, Hanabusa Kannon published a book in 2020 entitled ‘The Famous Mystery Writer of Kyoto that Nobody Really Knew.’ At one time there was an official website for Yamamura Misa, but it has (mysteriously) disappeared.

Books set in Kyoto

The number of books set in Kyoto is so extensive that rather than list them here, I will list the Kyoto locations or events that are featured in a sampling of her Kyoto works. My suggestion is that you pick a locale that you are familiar with and dive in. There are also a number of works that at least partially take place in Kyoto but don’t refer to a location in the title. Examples would be Kyoto Gourmet Journey, Kyoto Engagement Journey, Kyoto Honeymoon Journey and Kyoto Divorce Journey etc.

| Place | Title |

|---|---|

| Ohara | 京都大原殺人事件 (1984) |

| Sanjusangendo | 三十三間堂の矢殺人事件 (1984) |

| Sagano | 京都嵯峨野殺人事件 (1985) |

| Kurama | 京都鞍馬殺人事件 (1985) |

| Kitano | 京都化野殺人事件 (1986) |

| Aoi Festival | 京都葵祭殺人事件 (1986) |

| Kita Shirakawa | 京都北白川殺人事件 (1987) |

| Higashiyama | 京都東山殺人事件 (1987) |

| Nishijin | 京都西陣殺人事件 (1987) |

| Kōmyōji (Nagaoka) | 京都紅葉寺殺人事件 (1987) |

| Daimonji | 京都夏祭り殺人事件 (1987) |

| Maiko (Gion) | 京舞妓殺人事件 (1987) |

| Miyako Odori (Gion) | 都おどり殺人事件 (1988) |

| Murasakino | 京都紫野殺人事件 (1988) |

| Hanamikoji Street | 京都花見小路殺人事件 (1988) |

| Ninenzaka | 京都二年坂殺人事件 (1989) |

| Kibunegawa | 京都貴船川殺人事件 (1989) |

| Mifune Festival (Kurumazaki Shrine) | 京都三船祭り殺人事件 (1990) |

| Kiyomizu-zaka | 京都清水坂殺人事件 (1990) |

| Shisendō Temple | 京都詩仙堂殺人事件 (1991) |

| Nishioji Street | 京都西大路通り殺人事件 (1995) |

The books that feature the fictional Katherine Turner may also be of interest as they reflect some of the gaijin experience in Kyoto. The Japanese wikipedia entry for Misa Yamamura has a list of the books in that series.

General Resources Consulted

- Yamamura Misa — Wikipedia entry (English). A rather brief entry.

- 山村美紗 — Wikipedia entry (Japanese) Includes a list of her complete works.

- 山村美紗のおすすめ作品5選!ドラマ化も多くされたミステリー作家 (2021) — An introduction to five of her novels.

- 山村美紗おすすめ8選をご紹介~衝撃のトリックに酔いしれる~ — An introduction to eight of her novels.

- 山村美紗の作品一覧 — An annotated list of her books. Very useful.

Recent Comments