‘Hic svnt Dracons‘

by Alex Olivera

By way of introduction….

Louise Bourgeois once said that the artist who discusses the so-called ‘meaning of his work’ is usually describing a literary side issue, and that the core of their original impulse is to be discovered, if at all, in the work itself. It is under this light that I find myself introducing this novel, as if in a deep labyrinth of mirrors, hoping that the Minotaur will not get hold of me in the process.

I take this extraordinary opportunity to come out of my intimate ‘written realm’, and to look upon it. It feels at once familiar and strange… Familiar, for the core of this story has always been inside me, even if in different formats, such as music or art. Strange, for I am not quite sure about ‘who’ actually wrote it. In this sense, the writing process is perhaps not so much guided by a Muse, but by the characters themselves, quite frequently in a revolt which you need to make sense of in the aftermath.

This novel was born in the mountains of central Japan. I was taken by surprise, I had no idea where this was going. I wrote notes and more notes wherever I could; napkins, occasional booklets, supermarket tickets… Words and images kept pouring down and did not leave me for a full five months – fortunately by that time I had got hold of my computer.

By the end – and several kilos less – this story needed a name; it became Here be Dragons. It just could not be called any other way. Yes, I am aware it sounds ‘common place’, but as the story itself suggests, we tend to pass by things that seem too obvious. Is it not the case that the obvious is the most difficult to see? Dragons are masters of deception, after all. They represent the illusions of the ego, they are summoned to produce fear and keep us ‘at bay’.

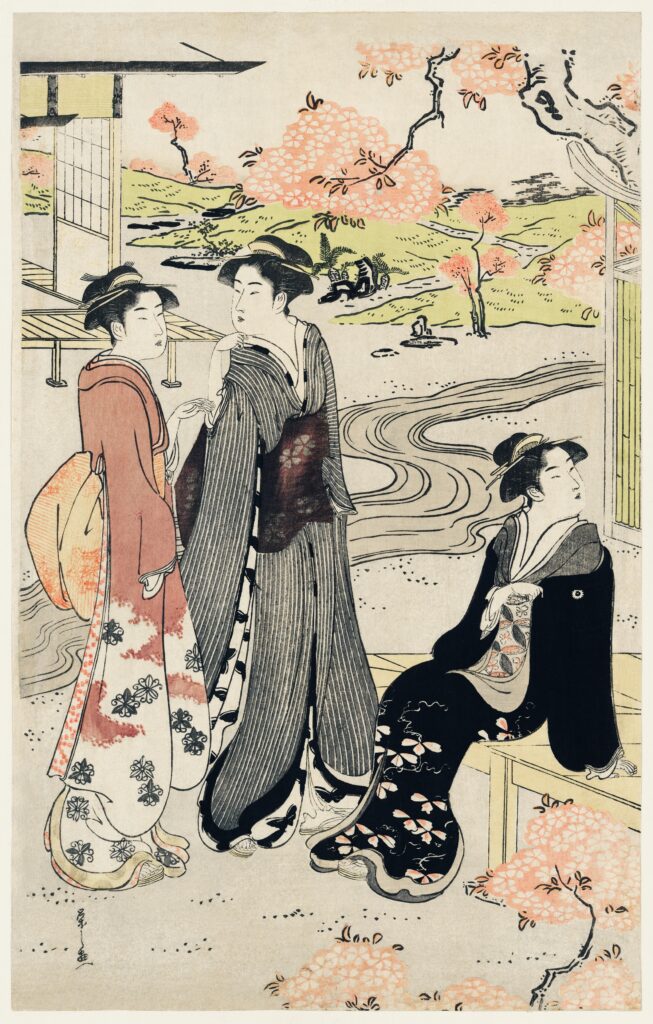

I would like to think of this novel as an intimate, historical fiction. It is set in Japan, touching different periods and social strata, where generations and personal saga flow slowly into a common sea. But as much as culture framed the stories, individually or collectively, the subject is still universal, for it is the drama of a search for love and a place in the world. So this story is also ours.

***********************

Novel extract

His mother had told him that, during the Meiji Restoration, his obā-san had lived in China with her parents and fourteen siblings, including her twin brother. ‘Out to the west, farther even than where the sun goes down,’ she said, ‘in the land of silk and gunpowder.’ In those days her father worked for the Japanese government. She was still only little when war loomed over the horizon. In a matter of days her family dismantled the entire house and packed up everything from the dinner service to the folding screens. They let the birds out of their cages and left at full tilt, returning to Japan aboard a Navy warship. Amidst all these hasty preparations and with so many children to see to, they had scooped up the little girl’s twin brother but somehow contrived to leave her behind. They were in the curious habit of counting the twins as a pair; add them together and they made one. This must have been the source of the confusion, for no one noticed the little girl’s absence until dinnertime, when they were already far out at sea. The nanny had counted and recounted them. But every time she totted them up on her fingers, she couldn’t work out where it was that she had gone wrong. So she lined them up, took the abacus out of her bag and counted one last time: the little girl was missing. In light of their daughter’s inveterate penchant for hiding, the family held out the hope she might still be tucked away inside one of the travelling baskets. ‘Could we have locked her in a trunk?’ they asked themselves, racing to the cargo hold. They rifled through the luggage – other people’s as well as their own – well into the small hours… but all to no avail. The little girl was nowhere to be found.

Communications were down due to bad weather; there was no way of contacting the Consulate. Still they tried and tried, regardless, all journey long, beaming out a stream of telegraphs but receiving none in reply. All they could make out over the radio set, crackling strangely in sounds not of this world, were Russian voices, possibly officers aboard other ships. By the time they put in at Tokyo, they were worn ragged with desperation. The mere thought of having abandoned their child, of having left her in such dire straits, triggered in them such shame that they agreed they would, in future, never own to having fifteen children, but fourteen. People were bound to forget, what with everything else that was going on… But, despite having only a vague notion of the exact numbers involved, their relatives remembered perfectly well there had been twins. So they set about pairing off the smallest girl and the remaining twin, they being the most alike. As they grew older, however, people began to suspect there was something ‘wrong’ with this impromptu sister, still a pint-sized dot next to her ‘twin’ brother. To make matters worse, as some of the children had been born in China – nikkeijin kids as they were known, a mildly derogatory epithet that they never quite succeeded in living down – the conclusion they came to was that the twin brother must have been switched for a girl in hospital, the birth of a girl having always been regarded as a tremendous misfortune in China. In all that time not a day went by without her parents secretly visiting the Foreign Ministry, or the Department of War, or any temple they could find to pray in. They began by invoking the Celestial Goddesses of China, believing them to be the most helpful, given their superior knowledge of the local geography, and who knows… they be mothers themselves – in some distant and ephemeral dimension, of course. But on further consideration they spotted a flaw in this logic: the two nations were, after all, locked in a ferocious war and no assistance could be expected from Chinese gods. That put an end to all their hopes. Three years on, they had resigned themselves to never seeing their daughter again and had given her up as dead. But no sooner was her name engraved on the traditional wooden funeral tablets for the family altar, than the little girl reappeared – no one could say where from – carrying a canary in a cage. She was delivered to them by a Chinaman with a long wispy moustache, who introduced himself as ‘Chin Li Foo Jr., Magician’. The girl arrived speaking fluent Mandarin and not a word of Japanese. But, despite a protracted conversation, neither party could understand a word the other was saying, so they agreed to communicate in ideograms, which they wrote on the black slate her brothers used for their homework. From what they could decipher – or rather, infer – the girl had taken a book from the Shin Doji Orai no Jiten Daizen collection, which had been sitting in a half-packed box awaiting removal. She had then apparently hidden herself away in the little tea-house by the carp-pond and fallen asleep. No one knew for certain how much time had passed before the good man found her wandering the back streets of Peking barefoot and alone, clutching her book for she was worth. Nor did they ever manage to solve the mystery of how she came to be in such a place. Still, what mattered was that the magician had taken her with him, treating her like his own daughter. The girl must have had several years of excitement as they moved about the country in their small travelling circus, but she remained forever tight-lipped about that period of her life. The fact that she had picked the first volume from the fukuro toji collection was another stroke of luck. On the first page of that particular volume, on the ex-libris, was written the address of the house where the family had previously lived in Japan and where they would be bound to return one day. Her father’s name appeared clearly: ‘Chairman Ito Yoshimi’, written in kuro sumi, and in immaculate calligraphy. Indeed, it was the only page to have survived intact. The magician received a substantial sum for his generous actions before vanishing back into the world whence he came. The girl and her family found it equally difficult to readjust to each other after such prolonged, involuntary exile. It was especially hard for her siblings, as she had learned a few tricks in their time apart, such as making biscuits vanish without a trace. Little did it matter if they used seven keys to lock her away; she would always escape her punishments; no one could do a thing about it.

*******************

More about Alex on her website and social media: https://alexoliveraj.wixsite.com/mysite/about

Facebook: Alex Olivera de Bary & Hic_svnt_Dracons

IG: https://www.instagram.com/hic_svnt_dracons/

Recent Comments