by Lisa Twaronite Sone

Sweeping the dust, that used to be my job at Hounji.

I also worked as a maid at a nearby hotel, but I liked being outside. So when my shifts there were over, I would walk over to the temple, pick up a broom and sweep for hours.

It didn’t pay much, but it was an easy job compared to making beds and scrubbing toilets. Sweeping was almost like meditation to me: swoosh, swoosh, swoosh, day after day, month after month, watching the seasons change.

I swept up the litter that collected next to the stone pillars supporting the old wooden buildings, and I swept the fallen leaves beneath the cluster of tall trees in the garden. Whenever it rained, I used the free water from the sky to sweep the grime off the paving stones. In winter, I tried to sweep away the snow as it fell, so it wouldn’t accumulate. In summer, I would sweep up the dead earthworms baked onto the pathways, where they had stranded themselves in a vain attempt to escape the relentless heat. I rarely looked up, only down, so I eventually came to know every square meter of Hounji’s ground as well as I knew my own body.

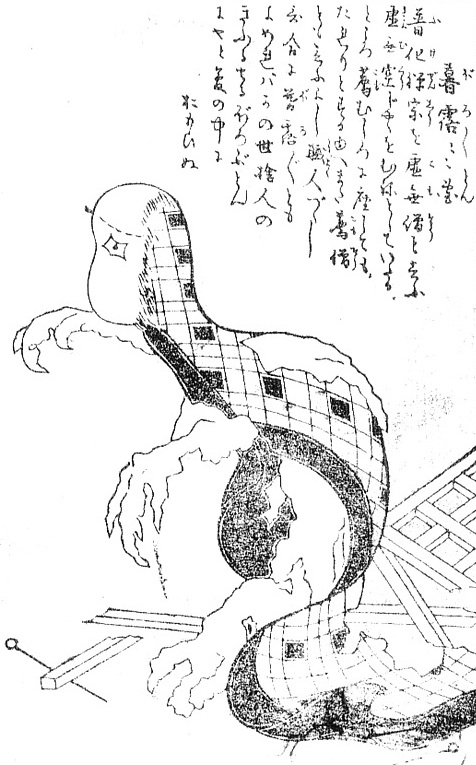

Hounji belongs to the Jodo sect but most visitors come to pray to its resident deity, a large stone known as Kikuno Daimyojin. The characters of the stone’s name mean “chrysanthemum field,” but some people think it was once written with kanji meaning “sharp,” which would make more sense. Kikuno-san’s sharp edges are said to have the power to cut away misfortune and bad relationships.

A few times a year, foreign tourists would wander off busy Kawaramachi Street into Hounji, and I had a chance to practice my English with them.

They always asked the same question, as they snapped photos of the straw dolls impaled with iron spikes that covered every inch of the temple’s lower walls.

“Is it….black magic? Voodoo?”

I would nod. That’s not exactly what it was, but it was close enough.

I had memorized some basic information about Hounji, which I recited for them.

“This place was a battlefield in the Onin War, so it had many demons. In 1567, the holy priest Genrenja Nenyo calmed the demons and built a hermitage here for people with disturbed minds. Kikuno-san is a spiritual stone deity that was believed to walk around the city of Kyoto before settling here.”

I then tried to explain what they clearly wanted to know most.

“People seek Kikuno-san’s help with separation. The straw dolls represent what they wish to separate from. Sometimes they want to separate from a person, so they wrap the person’s hair around the doll. They nail it to the building with their prayers.”

My description usually satisfied them. When it didn’t, my English was rarely good enough to understand their followup questions. And even when I understood what they were asking, I usually didn’t know the answers. I was only the sweeper.

I’m not sure, but I think the proper way to pray to Kikuno-san was to purchase the straw doll and the iron stake from Hounji. How else would the temple stay in business and pay its expenses, like my wages? I never had a reason to buy a doll myself, but I figured the information was probably posted in the temple office somewhere, or maybe people had to phone the priest.

Of course, people came with their own homemade dolls and nailed them to the building – often secretly after dark, but sometimes in broad daylight. And in addition to hair, they attached other objects to their dolls, even though they weren’t supposed to: documents, shreds of cloth, even food, like dried fish or plums, or partially consumed bread with jagged bite marks.

Someone at the temple – I never knew who – would remove the dolls adorned with anything besides hair, and they also periodically took down the old dolls to make room for the new ones.

I almost never spoke to any of the visitors leaving offerings, but some of them wanted to speak to me. Maybe they thought having a witness would increase the odds that their prayers would be answered?

“I’m putting a curse on my boss!” declared one young man in a business suit, brandishing his straw doll with a few white hairs wrapped around it. But then he stopped and blushed a deep red, and turned away from me – why? Was he lying, and ashamed? Were his prayers really aimed at separating from someone else in his life?

One middle-aged couple came together, and greeted me pleasantly. “We’re not here to curse anyone – we’re just praying to the deity to separate us from our bad luck,” the man said with a smile, but I noticed their doll was wrapped in so much hair that it completely covered most of the straw. Their “bad luck” obviously had a human form.

The majority of supplicants were women. Even though I stared at the ground as usual, it was impossible not to notice them: rich ladies in expensive silk kimono or the latest designer dresses, students carrying backpacks full of books, and workers wearing plain uniforms and cotton aprons like mine; high heels, zori, leather boots, and cheap plastic sandals covered their feet, as they marched, trudged or crept forward, all of them begging Kikuno-san to separate them from their troubles.

One chilly day in early spring, a tiny, elderly woman scuttled past me. She was wearing a bright green coat with a reddish orange woolen hat and matching scarf, the color of nandina berries in winter. I thought those colors seemed much too showy for someone of her age.

Something made me look closer at the straw doll in her hands, and I was horrified to see a baby’s pacifier bound to it with strands of thick, black hair.

My first thought was that she was someone’s mother-in-law, trying to get rid of her son’s wife – this was a common scenario. But cursing a baby was going too far! I decided to do something I had never done before, and speak up.

“Excuse me!” I said. “You can’t leave such objects here! Only straw dolls and hair are allowed.”

She turned to face me, and I was startled to see she looked younger than I was – really no more than a child herself. I had mistaken her for an old woman from the side because of her stooped posture and the deep lines of the frown on her face, which I now saw was tracked with tears.

“It’s my own hair,” she whispered, squinting beneath her furrowed brow. “I want to separate from something inside my body. And I wanted to make sure the deity understands this, so it doesn’t think I’m putting the curse on myself.”

I understood immediately.

She lowered her eyes. “My doctor said there’s a law, so he can’t help me without my husband’s permission. And it’s not…it’s not my husband’s.”

I didn’t ask whose baby it was. Was she an unfaithful young bride? Or maybe she wasn’t married at all, and a man had forced himself on her? Or had she eagerly consented because no one had ever explained to her exactly what might happen? And now she knew, too late.

“Don’t worry! You’re hardly the first young woman in your situation. There are lots of people in this city who can help you.”

I took a pencil stub out of my apron pocket, and then fished around for paper. I found an old store receipt and scribbled an address on the back.

I pressed the paper into her hand. “There’s a midwife in Fushimi. Ring the bell and ask for old Mrs. Saito. She’s very kind and gentle, and she won’t ask you any questions. You can pay her bit by bit afterward. She’ll even do it far along, but that’s much more expensive.” I glanced down at her belly – was it slightly protruding? “Don’t wait. Go as soon as you can.”

Then I looked up at her face, and was astonished to see a completely different person before me.

The shadows under her eyes and around her mouth had completely disappeared, or maybe they were just less visible because of the way her smile tightened her cheeks. It seemed as if her skin had actually changed color somehow, from ashen gray to milky white, and her eyes were now wide open, fringed with long lashes. She was actually beautiful.

She stepped forward, and for a moment, I was afraid she was going to kneel in the dust at my feet. Instead she did something even more unexpected: she clasped my hand in both of hers, and vigorously shook it, like a Western businessman closing a deal in a movie.

“Sorry for being so dramatic, but you saved my life! If I didn’t miscarry soon, I was going to buy a train ticket for somewhere far away and walk into the sea. I thought every doctor everywhere would just say what mine said, about the law.”

“I’m glad to help. I guess you didn’t need to do that after all,” I said, gesturing at the doll she still grasped in her hands.

“Of course I needed to do it – I came here with my offering, and Kikuno-san sent you to me! You’re a tool of the deity, and it answered my prayers.”

She handed me her doll, its straw slightly damp with her tears and sweat, and I took it. I would put it in my pile of sweepings, to be burned later.

This happened a long time ago. I worked at the hotel until it was torn down, and the Ritz-Carlton now stands where it used to be. I still sweep at Hounji sometimes, and I suppose I’ll keep doing it as long as I’m able.

Visitors still ask Kikuno-san for help, but the temple ended its doll ritual sometime back in the ‘80’s. They can now buy a ceramic disc and write their separation wishes on it and then smash it with a stone, which I suppose must feel satisfying – but probably not as satisfying as pounding an iron spike through hair and straw.

I think about the young woman from time to time, and even though I never saw her again I can still picture her face. I remember feeling sad for the little life inside her, about to end before it drew its first breath. What I recall most, though, was her transformation – her shining face, and her insistence that her own life had just been saved.

And I’ll never forget the lightness of my own heart that day, as I swept away our footprints in Hounji’s dust.

**************************

To learn more about Lisa, check out this interview with her.

To learn more about Hounji, please see an English explanation here.

Recent Comments