Poems and photos from Lake Biwa by James Woodham

spider walks the air

unspooling from his being

lifelines of silver

where the wind takes it

how light a life that’s floating

shadow on the sand

Santoka* walking –

nothing between him and death

haiku and sake

gift of his whole life

Santoka into the wind

ragged spirit free

reeds flailed by the wind

cry of the crow through torn cloud

sun smashed on the waves

crows hang the branches

with cacophony of sound

raggedly flapping

now and then a bird

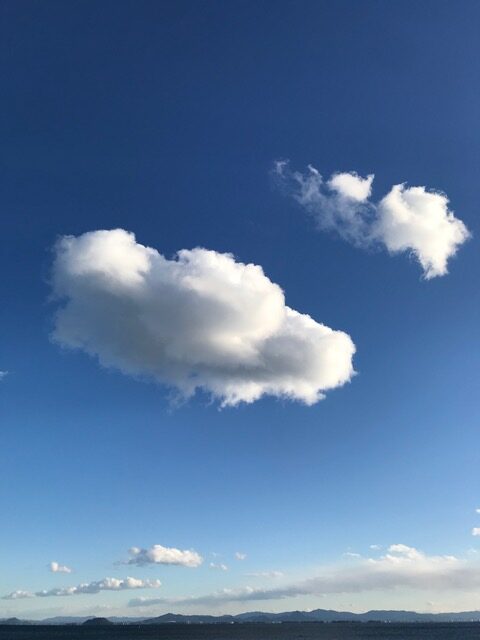

sends out its notes across the sky

carol to no one

bird song floats into

the mists of meditation

perches in the mind

blessing of the lake –

ducks given all this mirror

to float nothing on

ripples at the shore

pebbles underwater

clarity surreal

autumn still as glass

all the silence of the sky

all the lakelong blue

it’s all so clear now!

dust of a thousand days

wiped from the I-phone

lake instrumental –

sun sparkles random notes

jazzing the surface

yellow butterfly

leaves off writing its sky dance

to settle, a leaf

trail of ivy leaves

scarlet in the autumn sun

necklace for the rocks

the wind passing through

nowhere no one no body only

where it goes

the cat stops mid-scratch

leg still raised eyes caught

by the air’s movement

the cat unmoving

eyes slowly closing feeling all

that there is there

at the end of day

slowly flapping from the reeds

herohero** heron

hardly a ripple

the lake gunmetal grey

duck glides the silence

rain gentles the mind

giving it a space of grey

letting the thoughts drop

the rain relentless

a liquid blind of sound

drowning vision

wings soaked in sunlight

dragonflies under silver cloud

zipping the day up

the waves loquacious

liquid song unending

search for melody

Notes

*Santoka Taneda (1882 -1940). Free-form haiku poet, inveterate drinker, and lover of the open road, he walked the length and breadth of Honshu, Kyushu and Shikoku, an estimated distance of about 45,000 kilometres.

**herohero (Jap.): ‘completely exhausted’, ‘thoroughly worn out’.

********************

For previous contributions by James Woodham, please see the striking poems and stunning photography here. Or here. Or here. Or here. For his most recent postings, see A Single Thread here, or The Wind’s Word here, and for Vagabond Song click here.

Recent Comments