The Rinpa (or Rimpa) school of Japanese painting was created in Kyoto at the beginning of the Edo period. Its patrons were old aristocratic families as well as wealthy merchants who commissioned large-scale works on fusuma folding doors or byobu folding screens for their homes. Rinpa’s numerous artists gave us masterpieces such as the Wind and Thunder Gods, Matsushima, or Red and White Plum Blossoms.

However, when Japan opened to Western influences, the public as well artists themselves lost interest in traditional Japanese arts and instead tried to soak up as much of the hitherto unknown modern world as possible.

The government tried to slow, if not reverse, the decline of Japan’s unique artistic style that had been developed over hundreds of years of isolation. Policies were created to upgrade the status (and thus, the appeal) of artists who infused their work with the newly discovered modernism. The government also sent established (but young) artists overseas to experience and learn new methods and styles first hand. One of them was Kamisaka Sekka.

Kamisaka Sekka was born in 1866, just before the Meiji Restoration, into a Kyoto samurai family. His talent for art was recognized early, and at age 16, he started his studies under Zuigen Sunki of the Shiga school. Sekka’s acquaintance, the diplomat Shinagawa Yajiro, introduced him to European art and urged him to turn towards design. So, in 1888, he became a student of Kokei Kishi, an Imperial Household artist and designer. Through these different influences, he developed his own style and in 1895, he was awarded second prize for a design on an incense container.

In 1901, Sekka was finally able to do his hands-on research on European art, when the government sent him to the Glasgow International Exhibition. There, he was introduced to the Art Nouveau movement, which would heavily influence his later works. He was equally fascinated by the Japonism that had captivated the West and sought to understand which facets of Japanese art were most attractive to a Western audience.

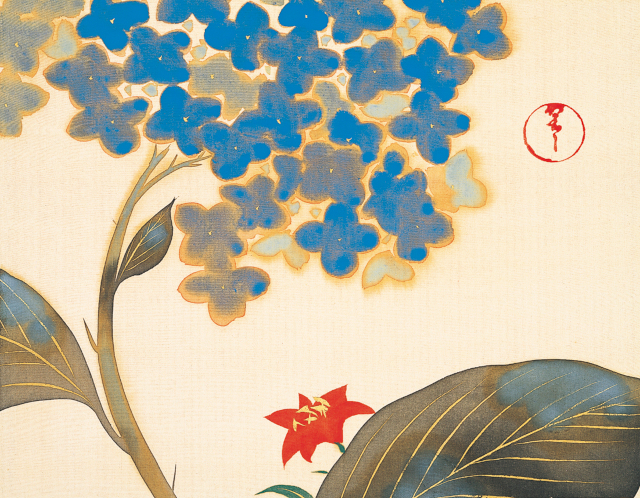

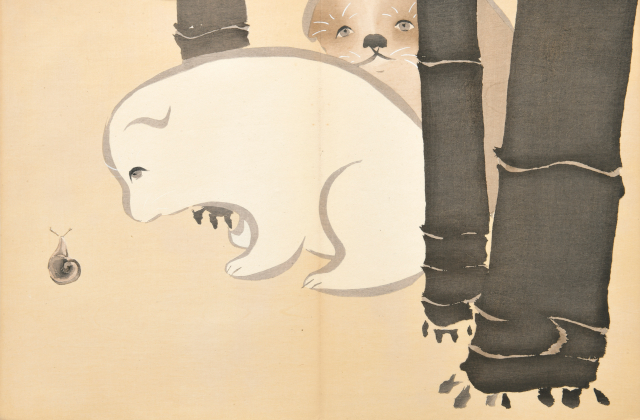

Upon his return to Japan, Sekka was determined to merge his new insights with his old teachings. He came to realize, however, that Japan already had an established decorative art —Rinpa. So, he took this as foundation for his experiments with Western methods and tastes, while the subject matter of many of his works remained rooted in Japanese tradition. Over time, he updated his style and became known for images that are reminiscent of rough designs rather than detailed paintings. They are often dominated by large areas of bright colors and show a unique sense of composition. Others described his style as “the return of Korin” (one of the Rinpa masters of the Edo period).

Like many artists in the Rinpa tradition, Sekka did not confine himself to large-scale paintings, even though he believed that painting skills should be the foundation of every designer. His designs can be found on tea bowls, fans, textiles, wrapping or writing paper, and pieces of lacquerware. Especially notable is his Momoyogusa (A World of Things), a set of 60 woodblock prints depicting landscapes, animals, flowers and both classical and modern themes, published 1909/1910.

Sekka’s influence reached beyond his designs and paintings, which he continued to exhibit regularly. He played a leading role in the Kyoto craft scene and from 1905, he taught at the Kyoto City School of Arts and Crafts. He also set up two of the forerunners of what would later become the Kyoto Arts and Crafts Institute. Sekka edited art magazines from the Meiji to the early Showa period, and in 1936 became a counselor at the Kyoto Museum (now called the Kyoto City Kyocera Museum of Art). In 1913, he was heavily involved in the Koetsu-kai, a tea ceremony created in honor of Hon’ami Koetsu, who is considered the founder of the Rinpa school of painting. Kamisaka Sekka died in 1942, aged 77.

Many of his paintings and other artworks have survived to this day. Kyoto’s Hosomi Museum has a large collection of his works, and currently, they are holding an exhibition focused on them. You can see “Kamisaka Sekka – Inheriting the Timeless Rimpa Spirit”at the Hosomi Museum until June 19, 2022.

**********************

All images (except the first: wikimedia commons) courtesy of the Hosomi Museum, Kyoto.