Is it true that only a suicide stops a Japanese train from running on time?

Why did her father always ask questions about death? In his last letter he’d asked if she knew anyone who had visited Aokigahara, the so-called Suicide Forest. He said he’d read about it in National Geographic, that you could sense the spirits when you walked through the trees. And did her husband, Paul, know anyone in his office who had died of karoshi – death from overwork?

Sophia pushed the letter back inside her bag, at the same time re-counting the six blister strips of painkillers with her index finger. Reassured by the feel of them, the whisper and rustle of the foil, she snapped the clasp shut and picked up her coffee cup.

The café was usually busy, but that afternoon it was almost empty. For the first time she was aware of the low, slanting light pouring in through the windows, the shoals of yellow leaves in the gutter, and she realised the season had changed without her noticing. Most people were taking advantage of the weather, enjoying the warmth of the October sunshine on their skin.

She drained her cup, stood up to leave, and as she crossed to the door the staff called out their thanks in unison: four ringing voices rising above the hiss of the Synesso machine and the background jazz.

‘Arigato gozaimasu!’

Sophia still found it impossible to tune out the everyday clamour of Tokyo: the cuckoo signals at pedestrian crossings; the J-pop and chirpy adverts blaring out from every shop; the cacophonous din of the pachinko parlours; the over-cheerful TV shows with their sherbet-pastel sets. At night, the lights added an extra layer of silent noise; a busy, bright chatter of flashing neon that crowded her head.

She’d been told that even in the villages it was rarely quiet. Her Japanese teacher, Fumiko, explained about the announcements and jingles which were broadcast through tannoys in the streets, how the sound carried on the wind to the rice paddies. When she asked why they didn’t complain, Fumiko shrugged and said there was nothing to be done. Shikata ga nai. It was not to be questioned, it was just part of life.

Sophia had tried to quieten the commotion inside her own head with a daily routine of coffee shops and art galleries, with the hush of museums and books, with endless walks through unfamiliar streets. But inner silence eluded her. She often remembered something her father said when she asked him why he spent so much time in the woods. He told her that solitude was the best companion, that in the wild outdoors it took on a different character, became in itself a connection to the world, an invisible cord between you and your true self.

‘I’m alone in the woods,’ he said, ‘but I’m never lonely.’

Sophia called out her thanks and goodbyes as she left the coffee shop, and by the time she reached Yoyogi Park she knew what she must do.

When Paul first announced he’d been offered a transfer to Tokyo, part of Sophia had held back, wanting to say no. Yet it was clear Paul thought it was the right time to go and that the move would be good for them.

He could no longer face seeing her grief, visible and raw, like an open wound, but she knew he’d simply stored away his own, buried it so deep that there were no longer any surface ripples. The loss of a baby wasn’t something to ‘get over’, it wasn’t a hurdle to leap and leave behind. It was a defining line; a line from which everything would be measured from now on: the time before Calum’s death and the time after Calum’s death. Grief had already become a part of the warp and weft of her, and at random moments it would rear up unexpectedly with a clatter of hooves. When it did, it was deafening. And unlike the everyday clamour of city life, the noise of grief couldn’t be silenced by earplugs or soundproofing.

They flew to Tokyo two weeks before Paul started work, moving straight into the tiny house in Yanesen which had been found for them by Himari, his new assistant. They could have lived in the company apartment block in Roppongi, but Sophia didn’t want to be in that part of the city, renowned for its nightlife, its brash expat community. She’d emailed Himari and told her she would rather live somewhere quieter, more traditional.

Himari had picked Yanesen, the area where she herself had grown up, with narrow streets and traditional shops, old wooden houses and a hillside location. A chance to breathe in the city. They were lucky; she found them a house rather than an apartment – albeit tiny. Two traditional tatami-floored rooms, one up, one down, with a small kitchen area partitioned off at the back.

When they viewed the upstairs, Himari opened the sliding screens in the bedroom to show them the enclosed veranda. It overlooked a pocket square garden of moss and raked gravel, shaded by three neatly manicured trees. The largest was a mountain cherry. The blossom had already fallen, and yet Sophia could picture it in full bloom, its pale pink petals newly unfurled. She imagined lying beneath it, looking up at the laden branches and the oblong of perfect blue sky above. The garden was edged by high fencing faced with bamboo screening, and houses similar to their own pressed in around every side. However, the outside space, Himari confirmed, was theirs alone.

‘I love it,’ Sophia said.

For the next two weeks they explored the area, bought new futons and bedding, vintage kokeshi dolls from a junk shop, slipware bowls and handmade wooden spoons from the hardware store. Himari suggested they have Western beds delivered, a dining table, but Sophia said no, she was happy with the house as it was: the low table and red floor cushions, the sliding cupboard doors decorated with mountain scenes.

The smallest things gave them joy each time they returned home: placing their shoes on the rack in the entranceway, seeing their indoor slippers side by side at the top of the step, inhaling the dusty scent of the tatami matting.

On their third weekend in Japan, they took a trip to Hakone, arranged by Himari and paid for by the company; a last chance to spend time together before Paul started work.

The bus from the station in Odawara was full of backpackers and sightseers, but as they wound through the main villages and resorts, the tourists steadily disembarked in ones and twos. The foreign tourists waved maps at the driver, checking and rechecking they were at the right stop, communicating in little more than sign language. As the bus climbed higher, Sophia suddenly noticed the tip of Mount Fuji through the trees. She grabbed Paul’s arm, her words tumbling out as she pointed, and the Japanese couple across the aisle beamed with pleasure at her excitement.

‘Fuji-san is very shy!’ the woman said. ‘You are lucky!’

The cloudless sky was cobalt, the snow-capped mountain a dazzle of white; a fleeting glimpse of something so beautiful that it snatched her breath away. At that moment, Sophia knew it was a sign of luck; she could feel it at her core. She sensed a calmness in these trees and mountains, knew she would never feel lonely in this landscape, that there was something essential waiting just beyond her reach. She had uncovered the edgelands of solitude.

After a kaiseki dinner served in their room, they made love on the tatami floor, a blue kimono spread out beneath them. It wasn’t urgent or hurried like the brief couplings they’d sought to try to block out death – those violent, bruising encounters that felt like bone on bone. It was slow and considered, and it confirmed, without words, that things could be good again.

Sophia’s fledgling happiness was short-lived. Paul was required to work long hours, and Sophia was expected to attend dinners with his British and American colleagues.

She found them unbearable. The men were self-important and rude to waiters. Their wives were brittle creatures with helmet hair and heavy jewellery. They spent their days shopping and lunching, and in the evenings they moved their expensive food around on bland restaurant plates and clawed at their husbands’ arms with scarlet nails. She was lonely and awkward in their company, out of step, just as she’d been uncomfortable in the London world she’d been pushed into before: champagne-fuelled celebrations in the boardroom accompanied by mutual backslapping; painful lunches with her boss; nights out at the latest West End bar with endless free drinks and unlimited bitching; Christmas parties at Quaglino’s. Her mother tried to tell her she would never fit in, that her Yorkshire accent and inability to conform would hold her back.

‘They’re not your people,’ she said, and Sophia knew she was right.

She had nevertheless tried in London, for the sake of her career. Here in Tokyo there was no need. Sophia didn’t want to fit in – didn’t need to fit in – to this sneering world of dismissive expats. She found reasons not to go out with them, until Paul eventually stopped passing on her excuses, and finally she was forgotten.

At first, Sophia enjoyed being alone: the peace of her tiny garden, shopping in the local markets for food, exploring the area. But as the summer wore on, she felt suffocated. Even the garden became too hot, the surrounding houses trapping the humid air. The only place to stay cool was in the air-conditioned room downstairs, and she felt hemmed in by its gloom. In Yanesen, the shopkeepers and locals were getting to know her, but they didn’t speak any English, and their reciprocal bows and smiles, their improvised sign language, could only take her so far.

She asked Paul if Himari could find her a suitable Japanese teacher, and she began to travel across the city to Shibuya three mornings a week to meet with Fumiko.

Fumiko dressed in linen shirts that were the colour of oyster shells and faded sky. She wore a thin gold chain around her neck which caught the light, and her hair was cut in a perfect bob. Sophia envied her quiet containment, her patience with mispronunciations and forgotten vocabulary. There was something about Fumiko which made Sophia want to try her hardest, and slowly she moved forward, adding new words day by day, words she was sure would reconnect her to the world.

She began by asking Fumiko questions about herself, but her responses were brief and reserved, and when Sophia suggested they went for a coffee, she politely declined.

‘I am sorry, Sophia-san, it would be very difficult for me,’ she said.

In the evenings, if Paul came home early, she tried to practise her Japanese on him over dinner. He was always tired and barely listened to her, switching on the portable TV as soon as the dishes were cleared, searching for English language news channels. He told her very little when she questioned him about work, and if she called him at the office, Himari would apologise politely and tell her he was too busy to talk.

Sophia was ignored, avoided, silenced, shut down. She was still disconnected, on the wrong side of an invisible barrier she couldn’t push through. Yet the noise of the city and the chatter within her head were both as loud as ever.

Emboldened by her new language skills, she began to explore every area of the city, to take day trips to surrounding towns, to spend time planning journeys to temples and mountains, often returning only at dusk to the house in Yanesen. Her anonymity made her invisible; a ghost moving through the crowds. No one gave her a passing glance on the streets, and in coffee shops and bars, although the staff smiled and nodded excitedly when she ordered in Japanese, they looked puzzled if she tried to engage them in any further conversation.

But after a few weeks, she no longer felt out of place in Tokyo on her own. She knew she could never make the city hers, that she was sliding along its surface and there was no way inside, yet it ceased to be important. She explored the streets and parks and galleries, the temples and the teahouses, and every other day, after her class with Fumiko, she drank coffee in her favourite café in Shibuya. As the world strode by the café window, Sophia looked on with calm detachment, and when she was tired of watching, she wrote in her journal.

She wrote about their neighbour, Mrs Kobayashi, who would knock on Sophia’s door and offer her a jar of homemade bean jam or a bag of anpan buns, and about their gardener, Kaito, who appeared every Wednesday morning.

He wore a twill waistcoat covered with pockets, from which he pulled clippers and twine and gloves. Standing on the wooden stepladder, he trimmed the small trees with the topiary shears from the storage box, then took the rake and the shuro broom from their nails on the wall and combed the gravel, tended the pot plants, swept away dead leaves. The first time Sophia saw him she went out to talk to him, but Kaito seemed uncomfortable in her presence, and even though she spoke in Japanese, he scarcely replied. So now she opened the screens before he arrived, then watched him from her chair on the veranda, soothed by his calm, measured movements, by the gentle, rhythmic snips of the cutters and the drag of the rake through the gravel. She sensed his contentment, the beauty and peace of his solitude, and she wished she could feel it too.

She recounted her walks through the city, wrote about the man she glimpsed changing his shirt in a doorway. He revealed a torso that was a riot of fish, flowers, geisha and warriors: the ink badges of a yakuza gangster. He was as colourful as the street fashionistas, but just like many Harajuku teenagers, his attempt at diversity only served to reinforce his conformity.

And she described the row of shoes – a man’s, a woman’s, a small girl’s – which she saw lined up inside an open doorway. Sophia imagined the family, laughing and talking over dinner, and the daughter, sleepy-eyed, as her mother kissed her goodnight. More than ever, she ached for the life she’d lost, yearned for a new life she barely understood.

She wrote often of her longing for silence, and of how only suicide prevented a Japanese train from running on time.

She never wrote about Calum: her panic as she’d reached into his cot, her clumsy attempts to revive him, about the guilt and the grief and the never-ending heaviness that pulled at her heart.

She didn’t write about the way Paul silenced her as soon as she tried to talk about their son, about how he drank every night after work in the hostess bars and entertained clients in the geisha districts. She didn’t mention that she sat on her own in their garden, waiting for him to come home while she listened to the neighbours’ chatter and laughter floating down from the open windows.

She didn’t write about how sad all of this made her.

Sophia met Akiro one evening when she was walking through the backstreets in Shinjuku. He was taking a cigarette break, standing in the doorway of the Night Owl bar, when he saw her peering up the steep steps. She had been wondering which of the tiny bars to venture into, reading the clusters of neon signs that flashed above the doors. He bowed and ushered her upstairs with a sweep of his arm. She ducked her head beneath a low beam as she went in through the hammered metal door, then sat down on the nearest bar stool. She was the only customer.

Akiro told her his name, asked Sophia hers as he placed a clean beer mat and a hot towel on the bar. Then he poured her a pale ale and lined up two small dishes of rice crackers. She drank the beer too fast, watched a black and white Kurosawa film on the screen behind Akiro’s head, listened to the thrum and pulse of music playing through two large speakers as tall as the bar, a tangle of electronic noise and hypnotic whispers which coiled around inside her head. He nodded towards her empty glass and smiled, opened two more beers, then reached beneath the counter for a bottle of whisky. And around ten o’clock, when no one else had come in, he told her she was beautiful and quietly locked the door.

He stood behind her, reaching around to slide his hand inside her shirt, but as she turned towards him he pulled away, pointing to the back of the bar. She walked in front of him, then stopped, unsure where they were heading. Akiro pointed to the table in the corner and nodded. He asked her a question, and although she didn’t understand the words, she knew straight away what he wanted, knew what he needed, knew that he had intuited she needed it too – a basic human connection, flesh against flesh. No eye contact, no words, no false promises.

Sophia turned away from him, undressed quickly, aware of him behind her as he unfastened his jeans. She gripped the edge of the table without turning to look at him and arched her back towards him. His breath was warm on her neck as he pressed her forward onto the cool metal surface, and when it was over she realised she was crying.

As she walked to the station through the neon-bright streets, the laughter and chatter of drunken salarymen spilling out from every bar, she understood that all the city could offer her was a different sadness, a constant feeling of jet lag, of disconnection, of things being not quite as they seemed. She was blinded by Tokyo’s density. There were no panoramic views, only a set of close-ups at point blank range, the disorientation of an unfamiliar landscape, the knowledge that she was slowly dissolving.

When she arrived home, she tiptoed up the stairs, holding her breath, then stared at her face in the bathroom mirror as though examining a stranger. She slipped her shirt over her head and noticed how grey her skin appeared in the fluorescent light, how dark her eyes were. She opened the cupboard door and took out the first aid box, reassured herself by counting the boxes of paracetamol and co-codamol. When they first moved to Japan, Sophia had been sure Paul would prove himself to be stronger than her, that he’d be her saviour. But although she thought about the pills less and less frequently, they’d always been there: a reassurance, a promise of a way out, a talisman perhaps – their presence a lucky charm in itself, their very availability warding off the possibility that she would ever need them.

For the first time since they’d arrived in Tokyo, she took out three of the boxes, dropped six blister strips into her bag and pushed the empty packs back into the cupboard with the rest.

She went through to the bedroom and saw straight away that the room was empty. As was so often the case, she was alone.

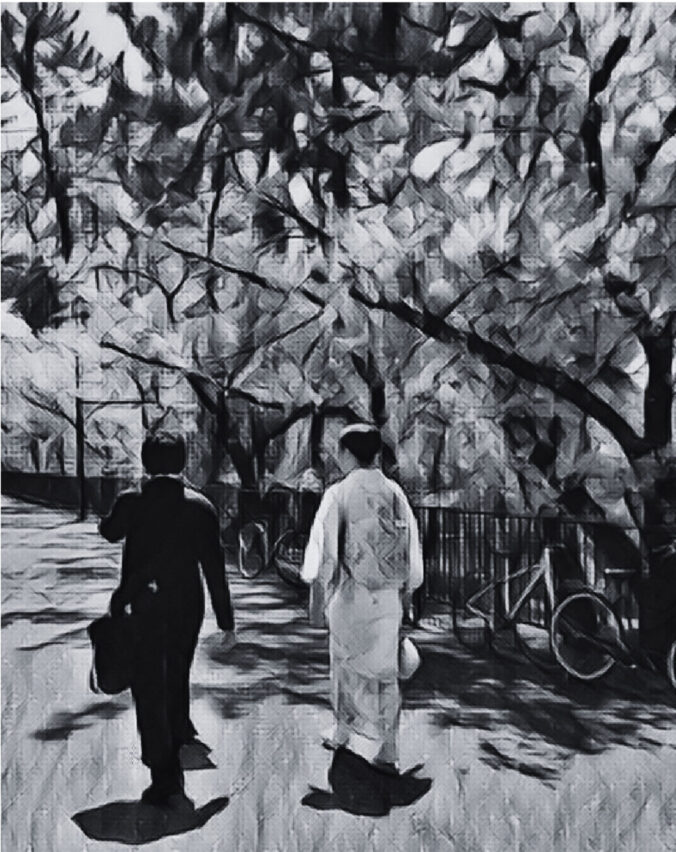

And the following afternoon, as she left the café in Shibuya, she made up her mind to find her own peace, her own solitude. She looked up at the trees in Yoyogi Park, the light shining through the red and gold leaves, the long shadows dappling the grass. She knew what she wanted and what she needed to do.

Without telling Paul or leaving a note, Sophia packed a bag and took the train to Matsumoto, then a bus to a village at the foot of the mountains. She walked up the steep hill to the temple lodgings, and they agreed she could take a room for as long as she needed.

She woke early the next morning, collected a map of the walking trails from the temple office and set out before the sun had risen over the higher ridges. She started her ascent through dense forests of larch and beech, following a trail marked by fluttering red ribbons tied haphazardly to branches and rocks. Her footsteps were muffled by fresh leaf fall, and she breathed in the scent of damp, mossy earth. There was a sharp screech from above, a rustle of leaves and cracking twigs as a family of macaques swung overhead.

As she climbed higher, she heard distant birdsong and the tap-tap-tap of a pygmy woodpecker. Her heart missed a beat as she crossed a narrow log bridge, gasping at the unexpected drop and the rush and tumble of white water cascading down the rock face. Eventually, she cleared the tree line and heard a bear bell tinkle faintly in the distance as a lone climber descended from the highest ridge: a yellow splash against the grey of the rock. Dropped into the silence, every noise had a clear meaning, each sound demanded her attention. She was finally connected.

Later that evening, Yua, the cook, asked Sophia to walk down to the pond with her to feed the carp. She told her how beautiful it was when the fireflies came, and of the Japanese belief that the tiny lights were the souls of soldiers who had died in battle.

Sophia thought about the fireflies as she lay on her futon, pictured one of the lights glowing brighter than the rest, imagined it was the departing soul of her own child. As she drifted between waking and sleeping, she watched it disappear above the temple and knew something within her had shifted.

She slept well that night, yet she was awake again at dawn, because as she’d already discovered, the mountains were as full of sound as the city. Outside her room she could hear the dry scrabble of birds’ feet in the guttering, the papery whir and flutter of their tiny brown wings. When she walked in the fields she was enveloped in the buzz and rasp and thrum of insects, the rustle of dry grass. At dusk there were the temple bells, the soft lull of the monks’ chants, and the gentle clink of pots and pans from the kitchen below her window.

And within this new noise, Sophia finally found her silence.

Amanda Huggins’ short story, “An Unfamiliar Landscape,” was first published in the anthology Same, Same but Different (Publisher: Everything With Words, 2021) and appears in the collection, Each of Us a Petal, published May 31st by Victorina Press.

Each of Us a Petal

The stories in Each of Us a Petal are all set in Japan or heavily reference Japanese locations in flashbacks within the pieces. The collection is unique in that the stories are told from many different perspectives: Japanese nationals, short-term residents, tourists, and those looking back on their time in Japan and its continuing influence on their lives.

This collection of short fiction takes the reader on a journey through Japan, from the hustle of city bars to the silence of snow country. Whether they are Japanese nationals or foreign tourists, temporary residents or those recalling their time in Japan from a distance, the men and women in these stories are often adrift and searching for connections. Many of the characters are estranged from their normal lives, navigating the unfamiliar while trying to make sense of the human condition, or finding themselves restrained by the formalities of traditional culture as they struggle to forge new relationships outside those boundaries. Others are forced to question their perceptions when they find themselves drawn into an unsettling world of shapeshifting deities and the ghosts of the past.

I set my stories in many different locations, but it is the people, landscapes and culture of Japan which continue to influence and inspire the aesthetic and sensibility of my writing more than any other destination. That said, I claim to understand nothing more than what it feels like to be human, whoever and wherever we are, and I hope that you will forgive me for sometimes writing about a Japan which exists only in my imagination. As Oscar Wilde wrote in 1889, “The whole of Japan is a pure invention. There is no such country, there are no such people.”

Amanda Huggins

To see Amanda’s prize-winning entry for the Writers in Kyoto Competition, please click here.

Recent Comments