(Read Part 1)

Secretary of State Stimson

When Herbert Hoover won the 1928 presidential election and offered Stimson the post of secretary of state, he accepted and resigned as Governor-General of the Philippines. The inauguration of the Republican Hoover as the 31st president of the United States was held on Monday, March 4, 1929. (In 1932, an amendment to the Constitution changed the inaugural date to the one we now know: January 20.) Stimson was, on March 4, leaving Kyoto for Tokyo by train, on his way back to Washington. Stimson’s diary, typewritten by this time, shows that he arrived in Kobe on Sunday March 3rd. Again there was a delay, this time on account of a storm in the Yellow Sea, and he and his wife arrived between three and four in the afternoon instead of the scheduled 11 a.m. They were met by the U.S. consul, the governor of Hyogo, the mayor of Kobe, and other dignitaries. The Stimsons left at 4:54 p.m. for Kyoto by train in a special compartment furnished by the government. They reached Kyoto at six o’clock and, as before, enjoyed a “very comfortable night in the Miyako Hotel.”

By this time the Japanese and world press were reporting Stimson’s every move. Photographs appeared of the couple in Kobe, and the local Kyoto Nichinichi newspaper even had a photo of them in Kyoto in the next day’s edition. The following morning they caught an 8:15 train and arrived in Tokyo at 6:35 p.m. One is tempted to say they obviously had no time for sightseeing in Kyoto and yet the Japan Times reported that they took the train “after a brief sight-seeing in the ancient city.” At 8 p.m. they attended a dinner given by the Prime Minister, Tanaka Giichi, in Stimson’s honor at the Foreign Minister’s residence (Tanaka also held the position of Foreign Minister). Members of the Japanese Cabinet, and all manner of dignitaries, attended.

It might seem that the night spent in Kyoto betokens a man with an obsession for the city but the facts support no such assumption. Originally the plan had been to go by ship from Kobe to Yokohama, but, as Stimson confided to his diary, “The delay at the piers made it impossible and we were obliged to make the hard journey across by land.” The Osaka Mainichi newspaper reported that “The banquet in Tokyo started at 8:00 p.m. Although there were no formal salutations, the guests talked about the scenery in and around Kyoto and exchanged pleasantries in a congenial atmosphere and dispersed after 10:00 p.m.” Stimson left Yokohama on the afternoon of the 5th on the S.S. Franklin Pierce, reaching San Francisco on the 20th.

Why did Stimson remove Kyoto from the target list?

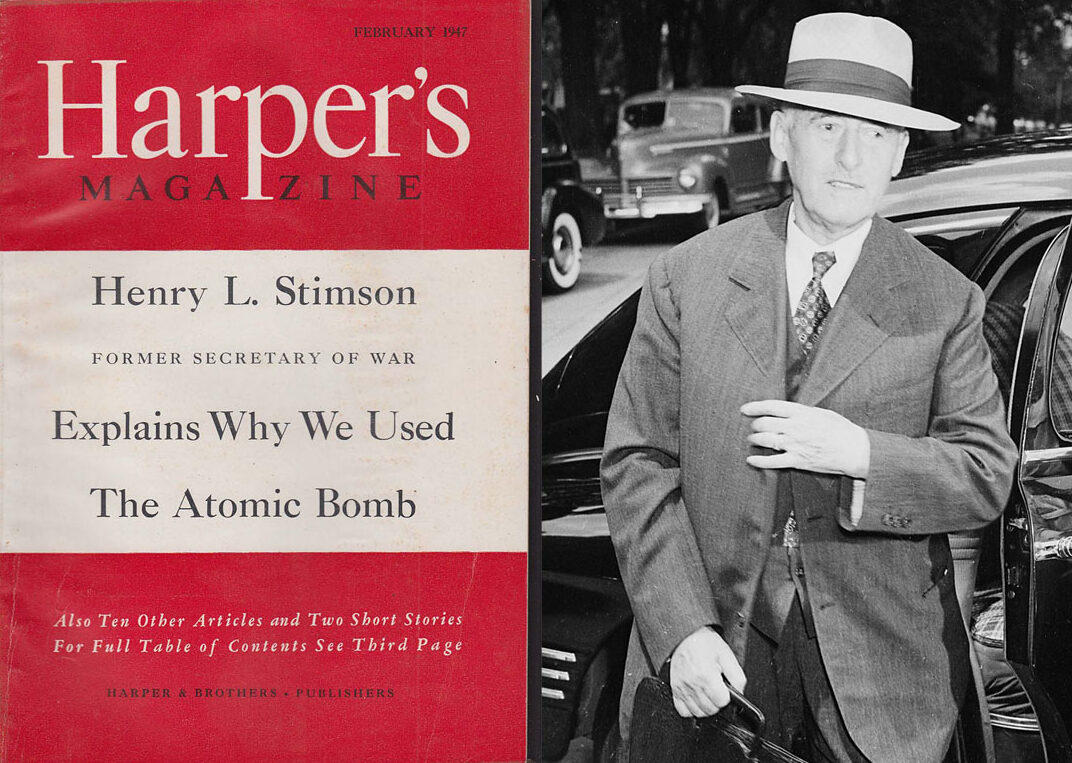

Stimson turned 78 in September 1945 and retired from public life. He suffered a heart attack two months later. In the post-war period a physically weak Stimson worked with McGeorge Bundy to produce an article to justify the decision to use the atomic bomb. The article appeared only after review and input from other important figures desirous to defend the use. It was published under Stimson’s name in Harper’s Magazine in February 1947, headlined ‘The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb.’ In it we read “Because of the importance of the atomic mission against Japan, the detailed plans were brought to me by the military staff for approval. With President Truman’s warm support I struck off the list of suggested targets the city of Kyoto. Although it was a target of considerable military importance, it had been the ancient capital of Japan and was a shrine of Japanese art and culture. We determined that it should be spared.” I don’t think this really explains why Kyoto was spared.

We need to consult Stimson’s diaries from the summer of 1945 and, of course, also the remarks of other important figures involved in the decision, such as General Leslie Groves, the Army officer who oversaw the Manhattan Project. Only then can we understand what was obviously a complicated decision. Scholars Alex Wellerstein and Sean Malloy have usefully discussed the topic.

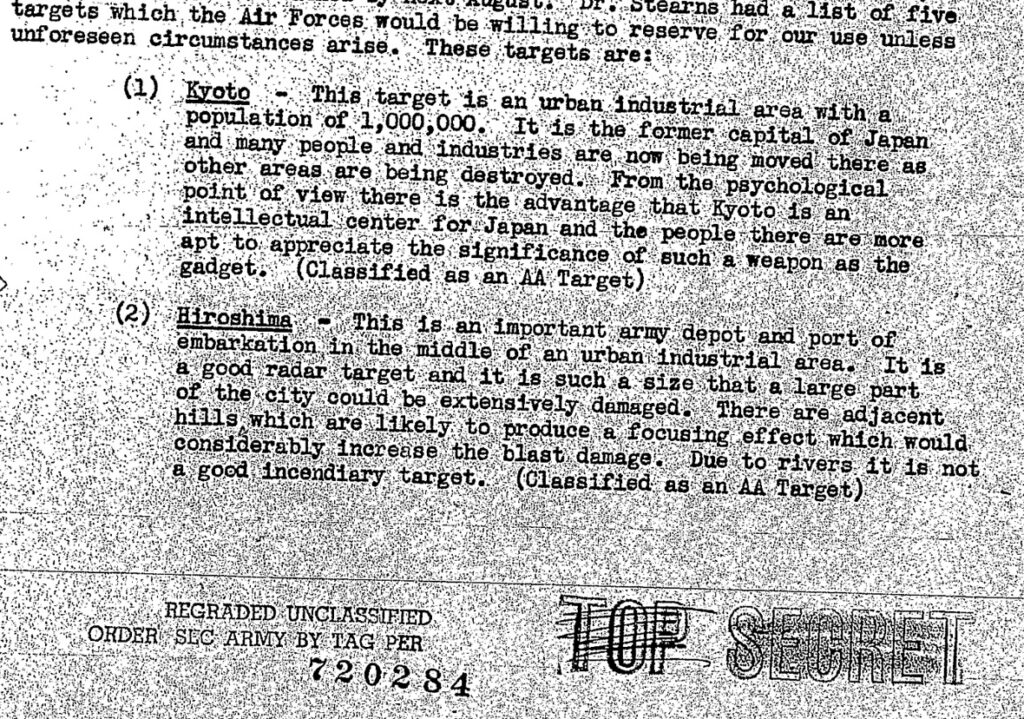

On 30 May 1945 Stimson found out from Groves what cities were on the target list for the atomic bombing. They were Kyoto, Hiroshima, and Niigata; of which Kyoto was the preferred target: “It was the first one because it was of such size that we would have no question about the effects of the bomb.” According to Groves, Stimson wanted Kyoto struck from the list: “[Stimson] went on to tell me about [Kyoto’s] long history as the cultural center of Japan, the former ancient capital, and a great many reasons why he didn’t want to see it bombed. When the [targeting] report came over and I handed it to him, his mind was made up as soon as he heard the word Kyoto. There’s no question about that. … He read it over then he walked to the door separating his office from General [George] Marshall’s, opened it and said: ‘General Marshall, if you’re not busy I wish you’d come in.’ And then the Secretary really double-crossed me because without any explanation he said to General Marshall: ‘Marshall, General Groves has just brought me his report on the proposed targets.’ He said: ‘I don’t like it.’” In reality Stimson rejected all three cities as targets at this time.

We can tease out three main reasons for Stimson’s protection of Kyoto. One reason, but surely not the most important, was that Stimson had been to Kyoto, was impressed with the city, and thought it would be a shame to see it destroyed. A second, and surely more important, reason was that he wanted to place the American bombing campaign on a moral footing. The Harper’s essay omits discussion of this and speaks of Kyoto’s ‘considerable military importance’. But his summer 1945 diaries show that Stimson persisted in the belief that Kyoto was a ‘civilian city’, and, as such, should be spared, whereas a ‘military target’ like Hiroshima might reasonably be attacked. Reality complicates this idea; we might conclude that Stimson was deceiving himself. By 1945 Kyoto was, in fact, producing war materiel, and the atomic bomb targeted central Hiroshima, the population of which was decidedly civilian. Perhaps 90% of victims were civilians. Wellerstein writes: “Stimson could not spare Japan, for many reasons, but he could spare Kyoto.” Stimson, while expressing his disapproval, had failed to make any effective objection to the firebombing of Japan. Part of the reason for the saving of Kyoto, I feel sure, was Stimson’s guilt over the firebombing.

In a diary entry dated 24 July 1945 Stimson said President Truman agreed that, if Kyoto were to be bombed, “the bitterness which would be caused by such a wanton act might make it impossible during the long post-war period to reconcile the Japanese to us in that area rather than to the Russians.” This third reason—the desire to have the Japanese aligned with the West, not the Soviet East—was surely the most important. President Truman and Secretary of State James Byrnes wouldn’t have seconded Stimson’s wishes but for this reason. The goodwill engendered by the sparing of Kyoto was one factor which made the post-war occupation of Japan a little easier to administer. As it happened, many Japanese mistakenly attributed the sparing of Kyoto not to Stimson, but to a general U.S. policy brought about largely by the actions of Langdon Warner, the art historian. This error makes for an interesting story, which I will tell on another occasion.

There are a couple more things to discuss. In 1953 Charles W. Cole, President of Amherst College, visited Japan. Otis Cary served as his interpreter. Cole relayed to him an anecdote he’d heard from John J. McCloy, assistant secretary of war under Stimson. This is how Cary remembered it:

“On a spring day in 1945, Stimson caught McCloy with a question in which he described Kyoto, her charms and heritage, ending with, ‘Would you consider me a sentimental old man if I removed Kyoto from the target city of bombers?’ After a little thought, McCloy encouraged Stimson to do so.”

I suspect this story and its mention of sentimentalism somehow misled Reischauer into thinking of honeymoons. In fact McCloy himself had been responsible for sparing the medieval town of Rothenburg ob der Tauber in Germany. Allied planes bombed it on 31 March 1945, toward the close of the war. But McCloy successfully arranged for the city to be surrendered, on 17 April, without being shelled.

In his book Japan Subdued (1961), historian and economist Herbert Feis speaks of “the chance events which fostered Stimson’s determination not to permit the bombing of Kyoto.” Feis’ error-riddled treatment of the affair continues:

“The Secretary [Stimson] had not known of the distinction of Kyoto as a former capital of Japan. But one evening during the early spring of 1945, a young man in uniform, son of an old friend, who was a devoted student of Oriental history, came to dinner with the Stimsons. The young man fell to talking about the past glories of Kyoto, and of the loveliness of the old imperial residences which remained. Stimson was moved to consult a history which told of the time when Kyoto was the capital and to look through a collection of photographs of scenes and sites in the city. Thereupon he decided that this one Japanese city should be preserved from the holocaust. To what anonymous young man may each of the rest of us owe our lives?”

Otis Cary quoted this story and made strenuous efforts to identify the ‘anonymous young man’—a feat he in due course achieved. The Stimsons had no children of their own, and doted on their younger relatives. Stimson was particularly close to Alfred Lee Loomis (1887–1975), a young cousin whom he treated like a son. And Alfred’s son Henry Loomis (1919–2008) proved to be the “anonymous young man” in uniform. The meeting in question took place in February or March 1945. Some readers have misunderstood Cary’s point. Cary wants to show that Feis is grossly inaccurate and that Henry Loomis was not, in fact, the impetus for Stimson’s decision. Firstly, Stimson knew of Kyoto’s long history from his visits there in the 1920s, a fact of which Cary was well aware. Underscoring the matter, as he understood it, Cary writes: “Loomis’ clear recollection that Kyoto was not discussed adds further weight to the idea that the sparing of Kyoto was Stimson’s own personal decision” (p. 17).

If there be any doubt, Cary also quotes McGeorge Bundy’s letter of 18 September 1974:

“[Bundy] recalled that at one point in [his] long collaboration [with Stimson] ‘the old gentleman explicitly denied to me that his attention had been directed to Kyoto by Langdon Warner and … he gave me to understand that he did not need instruction about the cultural significance of Kyoto from anyone’” (p. 17-18).

To finish, I offer remarks from two books. The first, Atomic Quest: A Personal Narrative (1956), is by Arthur Holly Compton, a Nobel Prize laureate in physics, and a key figure in the Manhattan Project. He says this of Stimson’s thoughts about Kyoto:

“The objective was military damage … not civilian lives. To illustrate his point [Stimson] noted that Kyoto was a city that must not be bombed. It lies in the form of a cup and thus would be exceptionally vulnerable. It is exclusively a place of homes and art and shrines.”

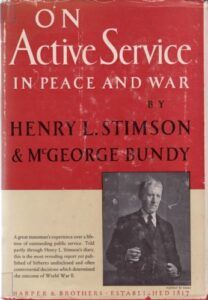

I would next highlight a remark by McGeorge Bundy. Bundy assisted Stimson in writing his memoir, On Active Service in Peace and War (1948), and became intimately acquainted with the matters at hand here. Stimson’s diaries dating to summer 1945 show that he hoped that the Japanese might be persuaded to surrender without the deployment of the atomic bomb. (This was a view he shared with Joseph Grew, former Ambassador to Japan.) In Danger and Survival (1988), the second book I’d cite in closing, Bundy wrote:

“After the war Colonel Stimson, with the fervor of a great advocate and with me as his scribe, wrote an article intended to demonstrate that the bomb was not used without a searching consideration of alternatives. That some effort was made, and that Stimson was its linchpin, is clear. That it was as long or wide or deep as the subject deserved now seems to me most doubtful” (p. 92-93).

I’d like to thank Mark Richardson for his invaluable help in writing this essay.

— Joseph Cronin