In the movie Oppenheimer (2023) there is a scene where the U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson is discussing the cities on a list of possible targets for the atomic bomb in Japan. There should be twelve but Stimson says, “Sorry, eleven. I’ve taken Kyoto off the list due to its cultural significance to the Japanese people. Also, my wife and I honeymooned there. It’s a magnificent city.” Apparently this scene regularly provoked a laugh among U.S. movie-theater audiences, presumably at the incongruity between the seriousness of the atomic bomb and the triviality of the fact of Stimson’s having been there on honeymoon.

The director of Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan, told the New York Times that the line wasn’t in the original script. The actor playing Stimson, James Remar, read the honeymoon story while preparing for his role. He enthusiastically relayed the story to Nolan, and Nolan let him add lines about it to the relevant scene.

It’s true that Stimson was responsible for saving Kyoto from the atomic bomb, and also from heavy targeted conventional bombing (there were a few instances of bombing within the city of Kyoto in 1945, leading to the deaths of 92 people, with a further 247 injured). Although he had visited Kyoto, in fact twice, the honeymoon story is false. Remar likely found it in a book, or even perhaps on Wikipedia. Within days of the release of Oppenheimer in the U.S. on 21 July 2023, the main page of the Henry L. Stimson Wikipedia entry was edited—on 25 July 2023, in fact—to remove the story. The Wikipedia editor who made the excision cited the nuclear science historian Alex Wellerstein, whose blog, Restricted Data, had a post—dated 24 July 2023—titled “Henry Stimson didn’t go to Kyoto on his honeymoon.” While Wellerstein’s instincts were right, he didn’t have all the facts. I give them here.

Henry Stimson married Mabel Wellington White on 6 July 1893. Henry’s letters to his bride-to-be discuss their trip to New Brunswick, Canada. The two would go canoeing up the Nepisiguit River, for a journey of a hundred miles. Stimson’s letters talk about buying Mabel a sleeping bag and the kind of clothing she would need (Reel 152). Henry doesn’t use the word ‘honeymoon’ but does say ‘our first trip together after our marriage’ (My Vacations, p. 75). Stimson had a great love of the outdoors. This was his third visit to the Nepisiguit. When he was eighteen, he spent two months of his summer traveling there accompanied solely by a native guide.

Where did the Kyoto honeymoon story come from? Edwin O. Reischauer (1910-1990), a Harvard University professor, served as the U.S. Ambassador to Japan for the years 1961-66. In his memoir My Life between Japan and America (1986), Reischauer wrote: “As has been amply proved by my friend Otis Cary of Doshisha University in Kyoto, the only person deserving credit for saving Kyoto from destruction is Henry L. Stimson, the Secretary of War at the time, who had known and admired Kyoto ever since his honeymoon there several decades earlier.” It’s ironic that Reischauer’s praise of Cary, who had written to correct common misunderstandings about who was responsible for saving Kyoto, came with a sting in its tail introducing yet another misunderstanding. Since 1986 the honeymoon story has appeared in a number of books and essays, though the 1987 Japanese translation of Reischauer’s book omits mention of it.

Otis Cary (1921-2006) was, like Reischauer, an American born in Japan of missionary parents, fluent in Japanese. In 1975 he published an article “The Sparing of Kyoto – Mr. Stimson’s ‘Pet City’” (Japan Quarterly 22 (October-December 1975): p. 337-347). Later that year the article was reprinted in book form, together with a Japanese translation that had first appeared in the September 1975 edition of the Bungei Shunjū magazine. Cary’s article carefully explains why Stimson, and not Langdon Warner, a Harvard professor and the Curator of Oriental Art at Harvard’s Fogg Museum, is the person responsible for the sparing of Kyoto from atomic bombing. Cary however had little knowledge of Stimson’s actual time in Kyoto and made one very unfortunate mistake. I aim to tell a fuller, more accurate version of the story.

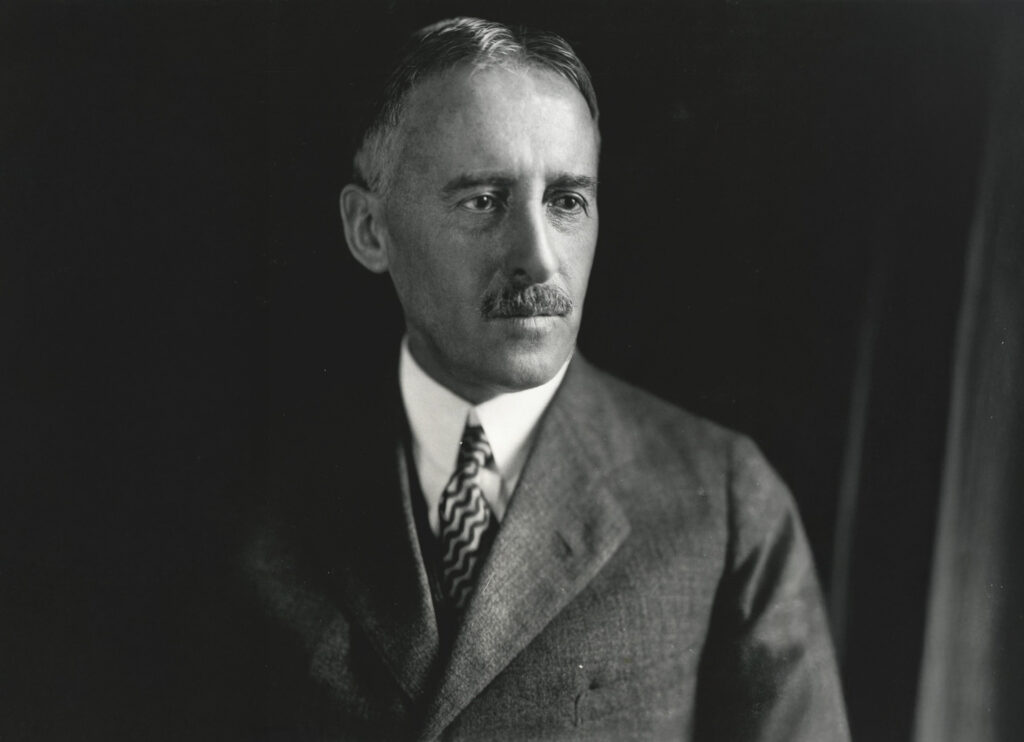

Henry L. Stimson

Henry L. Stimson (1867–1950) was a Harvard graduate. He became a successful lawyer and also served as a high-ranking politician. A Republican, he served as secretary of war (1911–1913) under President William Howard Taft, secretary of state (1929–1933) under President Herbert Hoover, and again secretary of war (1940–1945) under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman, who were both Democrats. Stimson’s visits to Japan occurred in the late 1920s. His friend General Leonard Wood (1860–1927) served as governor-general of the Philippines from 1921 to 1927. In 1926 Stimson spent a little over a month in the Philippines at the invitation of Wood. The purpose in making the trip was to investigate conditions in the country and offer advice as to what American policy should be. With the death of Wood in 1927, Stimson replaced him as Governor-General of the Philippines, a position he held until 1929, when he was appointed secretary of state in the new administration of Herbert Hoover. Stimson’s visits to Japan were, in fact, more or less incidental to his trips to and from the Philippines, which each time involved a voyage by steamship with stops in Yokohama and Kobe (and also in Shanghai).

We know some of the details of the 1926 trips to and from the Philippines from Stimson’s handwritten diary. The Henry Lewis Stimson Diaries are held in the division of Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library, New Haven, Connecticut. But they were microfilmed, many libraries have a copy, and I’ve consulted them. On 21 July Stimson’s ship, the President McKinley, arrived in Yokohama from San Francisco. For two days prior to arrival, Stimson suffered a bad case of lumbago, a complaint of many years’ standing; he didn’t stir from the ship. But his wife Mabel went ashore twice to see the shops and do some errands. Two years later Stimson’s diary notes that the U.S. Consul at Yokohama, Graham Kemper, together with his wife, had been kind to him and to Mabel in 1926. That episode likely dates to the July stopover. But it could also date to the return trip the Stimsons made in October, or indeed to both. In any case, on 23 July 1926 the ship arrived at Kobe. Here the couple went to the steamship company agent’s house and had lunch. The agent, a man by the name of S.A. Stimpson, had Stimson massaged “with great benefit” by a blind masseur. The Stimsons arrived in Manila on August 3rd.

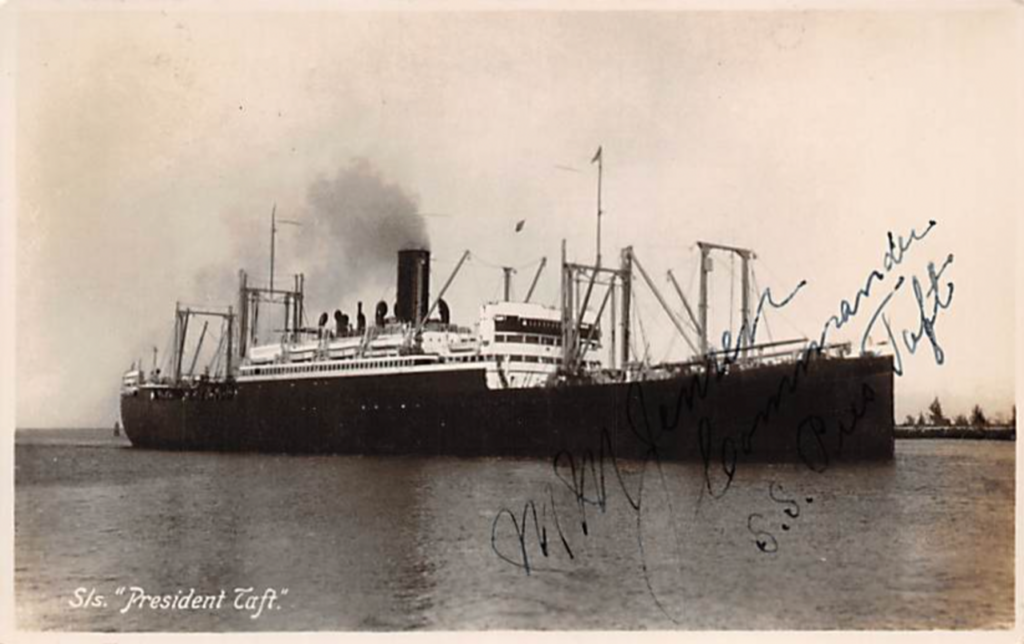

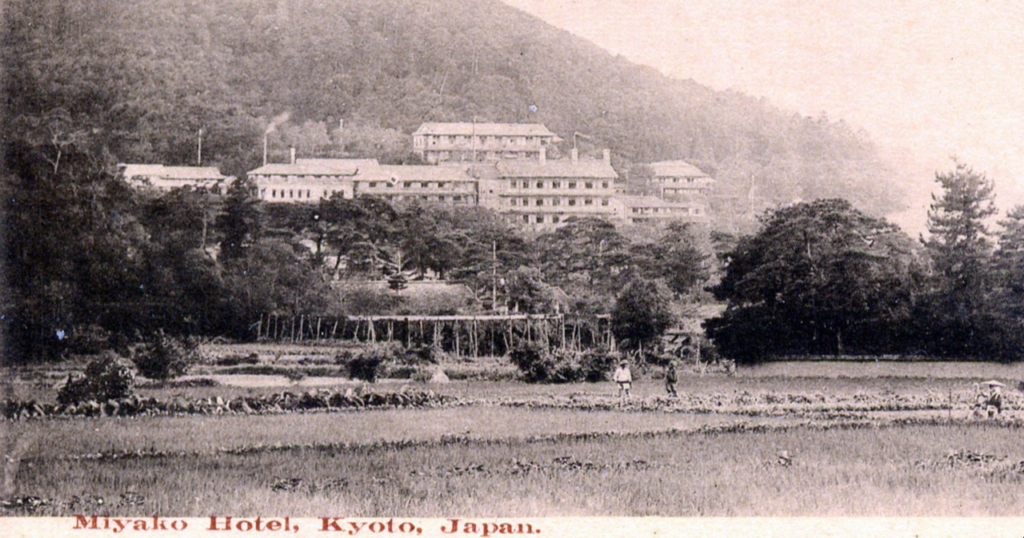

After just over a month in the Philippines the Stimsons departed on the long trip that would ultimately take them back to New York. On this voyage transpired what we might best call ‘Henry Stimson’s trip to Kyoto’. The couple first went to China: Hong Kong, Shanghai, Tientsin (now called Tianjin), and then up by river to Peking. After coming back to Tianjin a week later they took a boat for Kobe, arriving there on 2 October, delayed two hours by a broken pin in the steering gear. They were met at Kobe by the U.S. Consul and Vice-Consul. They transferred most of their baggage onto the S.S. Taft, and then packed lightly for the trip to Kyoto, arriving by train at 6 p.m. (also on the 2nd). For the evening they had a comfortable room and enjoyed a delicious dinner at the Miyako Hotel. Terry’s Guide to the Japanese Empire, widely used at the time, praises the Miyako, “a celebrated and popular hostelry” situated “high above the city” and possessing “the advantage of pure air, wide views, proximity to the chief temples, a charming situation and many home comforts.” “Some of the finest of Kyoto’s private landscape gardens are near the Miyako,” says the Guide. And “the scholarly manager of the hotel” was, by reputation, “a mine of information regarding Buddhist art, landscape gardening, etc.” (p. 400).

Sunday October 3rd was a beautiful day. The Stimsons went sightseeing, using the services of a rickshaw man recommended by friends. In the morning they went to Chion-in Temple, Maruyama Park, and Kiyomizu Temple. They also went to a Shinto shrine in Gion, which must mean Yasaka Shrine, and did some shopping. After taking lunch they headed north, going to a beautiful private garden; this will have been in the Nanzenji Temple area. Finally they went to the Silver Pavilion (Ginkakuji) a little further north. The diary ends here. The Stimsons’ sightseeing route that day, all in the eastern part of central Kyoto, is one I might recommend to visitors today who only had one day to see the city. In the late afternoon the Stimsons took the train back to Kobe. Their ship left that evening for Tokyo.

When writing his 1975 essay Otis Cary did not have access to Stimson’s 1926 diary and could not say exactly where the Stimsons had been while in Kyoto. He had, to be sure, suspected that Stimson visited the city. And, on searching records at the Miyako Hotel, he found what he was hoping to find: “Sure enough, ‘Mr and Mrs. H. L. Stimson’ had paid ¥30 ($15.00 at the time) for room #18 on October 2 and proceeded on to Kobe and returned October 30, to stay until November 4 in room #56, while #57 was occupied by ‘Miss Stimson’ for $14 a day.”

However, a 1987 reprint of the same essay silently alters one detail—an important one. The section just quoted now reads: “Sure enough, ‘Mr and Mrs. H. L. Stimson’ had paid ¥30 ($15.00 at the time) for room #18 on October 2 and proceeded on to Kobe and wrote to a friend, ‘I feel that we have duly sacrificed to the Goddess of Sightseeing!’” What has happened here? In the intervening years Cary had realized that the second group of Stimsons—in rooms 56 and 57—was another family altogether. In fact the Stimsons who checked in on October 30th were Mr. and Mrs. Charles Willard Stimson and their daughter, Miss Jane Stimson. No relation. The Japan Times of October 29th has them arriving at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo on October 27th. The error in Cary’s article means that to this day some people will imagine that Henry Stimson and his wife spent a lot more time in Kyoto than they did, presumably visiting such storied places as Nijo Castle and the Imperial Palace. Henry and Mabel spent one day in the city (2-3 October) and departed. Though three years had passed since the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, the damage was still obvious in Tokyo and Yokohama. Kyoto was, in 1926, much more of a highlight for visitors to Japan.

Stimson’s letter about sightseeing was in fact addressed to General Wood in Manila. The letter mainly consisted of very considered advice concerning U.S. policy in the Philippines, but it began with a private note: “We had a very interesting week in Pekin and afterward a day each in Kyoto and Tokio. So I feel that we have duly sacrificed to the Goddess of Sightseeing!” On the evidence of a memoir published late in his life, Stimson’s own taste in vacations was more for the wilderness, and for activities such as fishing and hunting. His personal interest in cities like Kyoto, though sincere, did not run especially deep.

From Kobe, the Stimsons went up by ship to Yokohama, checked in to the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, and did some sightseeing. The next day, October 5th, the S.S. Taft set sail at 3 p.m., with the Stimsons aboard. They reached San Francisco on October 20th.

In 1927 General Wood died and Stimson succeeded to the position of Governor-General of the Philippines. He departed from San Francisco on 3 February 1928 on the steamship President McKinley. At 6:30 on the morning of Monday, February 20th, Stimson arrived in Yokohama. He went to Tokyo where Prime Minister Baron Tanaka Giichi had arranged a special gosankai (luncheon) for him. There he met powerful political and economic figures, including Shibusawa Eiichi and Kaneko Kentaro. In an interview reported in the Japan Advertiser of the next day Stimson remarked: “I have known many Japanese Ambassadors at Washington and my firm has represented Japanese interests in law cases. My knowledge of the Japanese people and Japanese affairs extends over 20 years.” Concerning the ‘many’ ambassadors Stimson mentions, I might point out that this is almost certainly an exaggeration. On 2 February 1928 he told a Japan Times representative that “he was quite well acquainted with the former Ambassadors Shidehara and Chinda whom he met while they were stationed at Washington.” This was reported in the newspaper of the following day.

General elections were being held in Japan on this day—the first after the introduction of universal male suffrage. Despite the situation Tanaka seemed unconcerned. There was “an entire absence of electoral preoccupation,” says Stimson in his diary. “No telegrams were being received and the Baron seemed to be entirely detached from any anxiety.” Tanaka’s party won 217 seats, the opposition 216. On account of this one extra seat Tanaka kept his position as Prime Minister.

The ship left Yokohama at 6 p.m. The next morning everybody in Stimson’s group got up early for a spectacular view of Mount Fuji. The diary makes no mention of Kobe, so I suspect Stimson was extremely busy with preparations for the Philippines and mainly stayed on the ship.

On March 1st Stimson arrived in Manila and was immediately inaugurated as governor. For nearly a year he worked in the Philippines, loving his work. Stimson’s younger sister Candace Stimson came out to Manila later in the year. The Japan Advertiser of 29 November 1928 reports that, en route, she and a friend had arrived in Yokohama and would take the overland trip to Kyoto. They would then reboard the ship in Kobe.

(End of Part 1. Continue to Part 2.)