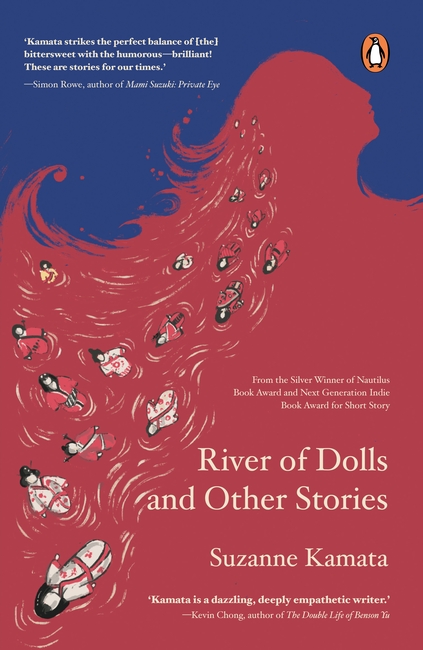

Written in eloquent vibrant prose, River of Dolls is a splendid collection of stories about mothers and daughters, girls and women, wives and ex-wives. Above all, this is a book about good mothers, bad mothers and those unable to be mothers.

Even the stories not overtly about mother and child have to do with familial obligations and resonate with tales of characters seeking fulfillment outside their responsibilities.

Kamata’s writing is visceral and vivid, her characters complex. The settings are various—urban and rural—but all are a slice of life. They leave us in the middle of a person’s journey, with no real resolution but often at an important juncture.

The book starts with what I thought was a memorable opening sentence, but turned out to be a perfect opening paragraph.

Every time Savannah speaks, a thousand magnolias bloom in my head. Her voice is liquid and sweet, like honey drizzled in the ear. There is none of the redneck twang that fills up the pool halls and laundromats. Her voice is worth imitating, and as I drive home after my shift at the restaurant, the smell of grease clinging to my hair and polyester, I sugar my syllables and speak into the night. (p. 8)

A lyrical paragraph, it works our imagination with its rich descriptions and contrasts, and takes us from the ethereal and heavenly to the greasy polyester realities of this waitress.

“Day Pass” tells the story of a woman who befriends a resident of the Women’s Correctional Institute on a work release program. The narrator is obsessed with the young enigmatic convict, but the story goes sideways when our narrator realizes that she may be in for more than she bargained for. This is a gentle yet riveting tale.

But “Day Pass” is only one of many beautiful stories. Some of my other favorites include “Blue Murder” about a farmer who falls in love with a kingfisher. He is a husband and father who feels unnecessary in his household and unappreciated. When he discovers this bird, he finds joy and purpose. He is mesmerized by it and believes “…that this bird had been sent to him in this moment of difficulty to ease his pain.” (p. 32)

“Down the Mountain” is written like an epistle or perhaps even a story told around a hearth to a daughter, warning her to leave her mountain village and pursue life in the larger world.

An American woman teaching English in rural Japan is the subject of “Lessons.” She is successful with the businessmen and children, but the housewives are challenging. In the end the lessons are reversed and it is the women who make their mark on the teacher.

In “The Snow Woman” we have a legend blended with a story of a Japanese mother obsessed with her mountain climbing. It is about a daughter who tries to understand why her mother would “… love mountains more than her daughter?” (p. 102)

In “Julia in the Desert,” a woman on vacation in Las Vegas with her family wonders, “What if I drove off the road, into the desert?” (p. 122) The title of the story, “The Lump,” is self-explanatory, and is enough to scare a woman into re-evaluating her marriage.

I have highlighted just a few, but all of the stories are worthy and should not be missed. They are thought-provoking and artfully written. All the characters are memorable including a rock-climbing violist from Prague named Greg Samsa, and a woman who prefers her ant farm to the Girls’ Day display. These two teach us that desire is transformative.

There is a mental patient in love with all things French, as well as an anthropologist fascinated with maiden sacrifices. And there is a family who feuds over everything, from meals to the atomic bomb, but it is in an A&W fast-food restaurant where they finally find a temporary peace.

I mustn’t forget the titular story. “River of Dolls” is a poignant tale about a woman struggling with infertility against the backdrop of the Girls’ Day Festival and the dolls central to that holiday.

These stories are set mostly in Japan, and are written with a deep understanding and appreciation for Japanese culture, and yet they are saturated with American sensibilities as well. It is a fascinating blend.

River of Dolls is ultimately a social commentary about how women’s identities are forged and about how difficult it can be for a woman to be just a person and not a mother, a daughter or a wife. It speaks to the responsibilities and the compelling needs of others as they compete against a women’s own needs and desires. Both touching and unsettling, River of Dolls will stay with you long after you close the book.