A Short Story by Rebecca Otowa

(Historical note: This story is set in the late 1580s, in the mountains somewhere between Kyoto and Nagoya. At that time, Japan had been for centuries a conglomerate of lots of little strongholds based on clans, much as England was before King Arthur. Three men emerged as “unifiers” of the country in the late 16th century, all from Nagoya. The first was Oda Nobunaga, the second (during whose time of power this story is set) was Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and the third was the ruler during the early Edo period, Tokugawa Ieyasu. Hideyoshi presided over Japan for many years, during which time (late 1580s) he put into practice the law that commoners were not allowed to carry weapons. There were searches of commoners’ dwellings (katana-gari) in those years, with some people being killed. It was not a wholesale bloodbath as in former times, however; Hideyoshi, then in his heyday, was turning his considerable talents away from fighting to political control and social structure. He thought up the precursor of the rigidly defined social strata that was made common practice in the Edo period, where samurai were at the top, followed by farmers. Hideyoshi, a commoner himself by birth, knew the importance of the common worker, especially the farmers, without whose support battles could not be won and campaigns would fail. This is the story of one such farming family.)

Momo ran through the mud of the dooryard with a bundle of dried grass stems. She was helping her father, Shinbei, with repairs to the thatched roof of their farmhouse. Shinbei stood halfway up a handmade ladder leaning against the eaves, waiting for her. “Come on, hurry up, Momo! I have a lot of work to finish by nightfall!”

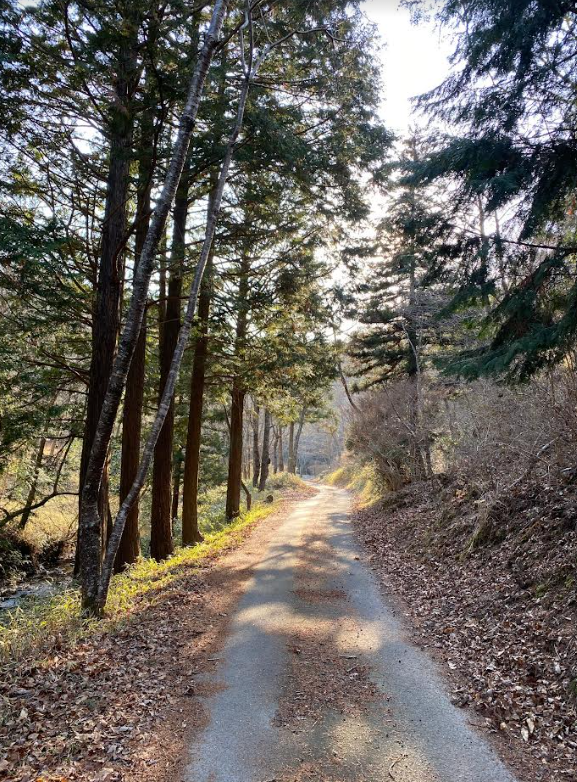

Momo put the bundle into his outstretched arm and as he climbed up the rest of the way, she raised her face to the sunlight and took a deep breath of the clean, piney, foresty scent that always surrounded the house, especially now that summer was almost here. The woods and the steep uphill paths of the mountains began just beyond their back door. She listened for the hammering sounds of woodpeckers looking for their lunch in the trees, and the sounds, which were everywhere, of hundreds of frogs trying to find their mates and fertilize the wobbly masses of eggs that would soon ring the swampy puddles, leftover from the recent rains, that had formed further down the valley.

Momo had just had her twelfth birthday (she was named for the peach blossoms that came out, magenta-colored and breathtaking, in May). She was barefoot in the mud and dressed in a hand-woven earth-colored kimono that came to her knees, a hand-me-down from her mother, with the extra material of the sleeves caught up and sewn at the shoulder, and the hem which flapped against her thighs heavy where it had been turned up and would be let down as she grew. Her long hair was tied at her nape with a spare piece of cloth. She had a flat, pleasant face, like her mother’s, now a little smeared with dirt.

Suddenly, a noise brought her father down the ladder and her mother stepping out of the doorway of the house, wiping her hands on her kimono. It was a noise of horses and shouting men, just within hearing distance, and it came from the mountain. As one, the little family turned toward the sound. From inside the house came the muffled cry of Momo’s youngest brother, two years old, awakened from his nap. The shouts turned to screams as they listened, and then they knew what they were hearing – not another military party come to requisition food, but a minor battle between samurai warriors in the years-long struggle for supremacy of the whole country of Japan. It was whispered that this involved all the high-class fighters in the region. Sometimes they heard the noises of fighting or marching in the mountains nearby, and occasionally a messenger would run through the village, carrying presumably important news from faction to faction. Sometimes they even heard popping noises, and Shinbei had told them, having heard it from someone in the village, that a new kind of weapon had been introduced after being discovered inside a shipwreck from far away – a kind of stick that was filled with black powder and could throw death from a great distance.

Shinbei herded his women into the house, pulled the door shut, and told Momo to make sure that her other two younger brothers, aged eight and six, were safe. They were – she had just seen them making rope from straw inside the house. The family would have to hide until nightfall, because there was a danger that wounded men would come down from the battle site and demand succor. So many military requisition teams had already come past their house, leaving want and destruction in their wake; if they couldn’t find what they wanted, they would push over an outbuilding or piss in the yard. The domestic animals – ducks and a pair of goats – were long gone, vanished down the throats of famished soldiers, and lots of other provender, carefully hoarded since last fall, was gone too. The hole where radishes had slept the long winter through under layers of straw was empty, and the mother and children had been foraging in the forest for ferns and fruits to eke out the time until the summer vegetables would be ready.

And that was not all. Momo’s two elder brothers had been taken as foot-soldiers, and her two elder sisters also taken by the armies, though Momo had no idea why. Those who were left of the family were either too old or too young to be of use to the military men.

The family hunkered down, breath caught and held, in the fragrant darkness pierced with a few lances of sunlight from the holes in the roof, listening for all they were worth as the screams died down and the ordinary sounds of birds and animals returned to the forest.

When the sunlight ceased to pierce the roof and darkness gathered in the corners of the house, Shinbei commanded his wife to light a lantern and took it in his hand, pushing the door open and conning the dooryard for signs of disturbance. There were none. Sighing, he stepped outside, took up a bundle of grass stems that had fallen from the roof, and said to no one in particular, “I hope it doesn’t rain tonight, I have to get that roof fixed tomorrow.” He handed the lantern to his wife and the evening’s tasks began.

* * *

The next day, and a few days after that, dawned bright and clear, and Shinbei, assisted by Momo, was able to fix the roof thatch. But as she ran to and fro with armloads of dried grass stalks, she noticed something new, and finally called up to her father.

“Father, do you smell something?”

“Like what?” he panted.

“Like when the goat’s baby died – something rotten.”

Shinbei sniffed the air, caught the ribbon of decay, and immediately stepped carefully over the straw to the top of the ladder. “That’s the smell of corpses that lie around after a battle,” he said as he climbed down. “Now that that smell has begun, dangerous wild animals have had their fill and won’t come near. Now is our chance!”

“Of what?” asked Momo, appalled by the vision of a whole valley of rotting corpses, lying in various awful poses among the trees.

“To go up there and see what we can take! Get ready to go, and don’t forget your foot covering.” Shinbei ran toward the house, where his wife was sitting on the bench by the door, busy with some task involving separating seeds from dried heads for planting. “Come on, we have to go now before some other villager notices that smell!” She stood up immediately, scooped up the baby from where he was playing in the dirt, and tied him onto her back, yelling for the other children to come as well.

In a few minutes Momo was following her father through the new bracken up the mountain, and the rest of the family were coming along behind. All of them wore hand-woven grass sandals to protect their feet from the brambles which were just starting to grow. They walked quietly, heads down, until they came to a clearing at the side of which a spring freshet bounced and tumbled over rocks. Here, under the morning sun, about twenty dusty and bloody heaps of rags were scattered about. A dead horse bulked next to the stream. The smell was much worse here, and Momo tied a piece of cloth, that she had worn around her neck, over her mouth and nose, which helped a little. She could see, out of the corner of her eye, the rest of the family doing the same. They advanced slowly into the clearing. Several ravens rose up cawing angrily at the intrusion.

Most of the corpses had already provided food for animals. Momo glimpsed an arm, half eaten, lying some distance away in the grass. The faces were not so bad, because the eyes were mostly gone, probably down the gullets of the very same ravens they had disturbed. Insects and worms had not had time to burgeon yet. Momo’s mother began to strip pieces of cloth from the corpses with her short knife. She and Momo collected pieces of cloth, tying them into bundles with other pieces. A few banners, white with indigo-dyed family crests on them, lay here and there. Cloth was mostly all that was left. Helmets, leather straps, metal fittings, and other gear would have been taken by the jackal people that always followed battles, looking for things to sell. But cloth, washed with ash in water and dried in the sun, could be sewn together to make raincoats or bedding. Momo’s mother was a thrifty woman, and woven cloth was valuable in ways that leather and gold weren’t.

Meanwhile Shinbei walked here and there with his sons, looking for something valuable that might have been overlooked by the jackals. He paused, looking sideways across the field to detect the glint of metal. Suddenly he straightened and ran toward the edge of the woods a little way away, where seedling scrub and young trees were just beginning to grow.

He let out an inarticulate cry as he came to a corpse that lay on its belly just where the mature trees began. The cloth that remained was better-quality than that which draped most of the other corpses. The arms and hands reached out toward the forest, as though the man had dragged himself this far in an attempt to escape. Protruding from underneath his body was a glint of gold.

Shinbei used his foot to roll the corpse over, and disclosed a short sword, scabbarded, with a golden hilt. It now lay on the ground half hidden in mud. Perhaps the man, who was obviously a high-ranking general, had had some idea of cutting his stomach in suicide if the battle didn’t go his way. But everybody had died in this battle, including this proud samurai. Nothing remained to show what clan he had belonged to. His face was almost unblemished except for a broad smudge of dirt down one cheek, and his fatal wound was in the belly, which had bled and stained the ground for a good distance around. His eyes, still intact, looked up at the sky. Shinbei bent and clutched the short sword as if in a dream. His family, attracted by his cry, gathered round.

“Look!” said the father. “We will be able to eat again!” He tucked the sword into his sash and looked off into the distance as his wife and Momo rapidly cut the trailing cloth from the body and rolled it up into a bundle. The family instinctively knew that the foraging was over, and they started down through the forest toward their house at the foot of the mountain.

As they walked, Shinbei thought long and hard about where to stash the sword until he could sell it to an itinerant peddler. He had no idea of using the weapon himself; it was so high-class that everyone would know he had stolen it. Best to get rid of it quickly, turning it into something that his family could use. We can’t eat gold and steel, he thought with a grin. He decided to hide the sword under a pile of trash, old moldy mats and straw, in the barn. When they arrived at home, he immediately went and did so, without a word to anyone.

* * * *

It took about a week for the smell of the decaying corpses to subside and for the breeze down the mountain to blow sweet again. It was a week of nightmares for Momo, but she knew better than to mention it to her parents. They resumed their spartan life. Shinbei asked discreetly among the villagers if a peddler was due any time soon. No one knew.

On a cloudy, humid morning a little while later, the sound of shouts came up from the village. A little while later, horses’ hooves sounded on the well-worn path that led to the little family’s dwelling. Shinbei looked up, startled, from his work of fixing a handle to a carved wooden hoe, and saw several men approaching. He put his hand behind his back and with it, motioned for his family to hide. He saw Momo move rapidly toward the house, but didn’t dare call out to give the alarm. The house door closed silently.

In a twinkling Shinbei was surrounded by three or four heavily armed men. One of them knocked him to the ground and put his foot on his back as he sprawled in the dirt. Another stood to one side and unfurled a piece of paper – it looked very white to Shinbei as he saw it from below, even though the sky was obscured by clouds. This man began to speak in a measured tone – he seemed to be reading from the paper, but Shinbei had never learned to read and didn’t know.

“By order of the supreme Shogun, all commoners are ordered to relinquish weapons! No commoner is permitted to possess a weapon from now on. If you have any weapons, get them out and give them to us!”

Shinbei thought quickly. Whether he gave them the short sword or not, he would probably be killed. They might not find it if they searched. His only chance was to lie. If he died, his wife might find the sword and sell it to save the remaining children.

“I have no weapons! I am just a simple farmer!” he shouted as best he could into the dust.

The man above him ground his heel savagely into Shinbei’s back. “Shut up! How dare you speak! We will search.” He jerked his head toward the others, who moved right away toward the outbuildings. Shinbei swallowed and closed his eyes.

In what seemed like a very short time, one of the men returned brandishing the short sword. “Look what I found!” He gave it to the leader with the paper, then turned to the others. “Anything else? Knives, anything?”

They said no. One of them picked up the hoe Shinbei had been working on and held it aloft. “What about farm tools? They could be weapons!”

“Our orders are not to leave the commoners, especially farmers, with nothing to continue their lives,” said the leader. He thrust the short sword into his belt on the right side. “However, this man must be punished – it’s clear that he stole this sword from someone much superior to him, and he lied about it! Off with his head!”

One of the men drew his long sword from his hip scabbard and swiftly brought it down on Shinbei’s exposed neck. He had no time to feel any pain – his head rolled under a nearby cart and his body shuddered and relaxed. The executioner wiped his shining blade on a tuft of grass and returned it to its scabbard. The men mounted and rode away.

Momo and her mother watched them go through a chink in the house wall, and when they were well away, opened the house door and rushed to the body of the father. Momo recoiled when she saw her father’s eyes looking at her from underneath the cart. The mother took her husband’s feet in both hands and dragged his body out of the dooryard. “I’m going to bury this in the radish hole,” she said over her shoulder. “That way the smell won’t give it away. Don’t worry, we will manage somehow.”

Momo took a deep breath and plucked her father’s head from the dust, closing the eyes and cradling it as she followed her mother around the side of the house.

It began to rain.

* * *

Rebecca Otowa is the author of The Mad Kyoto Shoe Swapper, At Home in Japan, My Awesome Japan Adventure, and the creator of 100 Objects in My Japanese House. Her many valuable contributions to Writers in Kyoto, including stories, interviews, and reviews, can be found throughout our website. Rebecca provided all of the photos for this story.

Recent Comments