July 16, 2023 | Irish Pub Gnome, Kyoto

I’ve been thinking about tonight’s theme: Words and Music.

Seems to me we are here basically to listen—and to be gently surprised by what we hear.

Mostly we think of things we do as actions, but even taking a walk may be not so much about a transitive physical activity, but more about simply creating an opportunity to look and listen.

Anyone who noticed my ‘Local News’ piece in the recent WiK nature anthology might know that I am particularly into listening. In this spirit, here’s a short follow-up to ‘Local News,’ from a little collection I put together recently with the non-boundary-pushing title of Reflections.

Please don’t think that I imagine this to be a poem. It’s more like an amateur footnote to the Theory of Relativity, as it applies where I most enjoy spending my time:

Moments at Sakahara

Low hills shield Sakahara from the constant hum of Kyoto city. From the fields that we farm, I hear only the sounds emanating within the valley. Close by, water burbling, crickets trilling; over in the forest, birds calling.

Compared to light, sound travels slowly. A thunderclap lags behind the lightning flash; when a jet plane passes far overhead its sound is heard from empty sky somewhere behind it.

A bird call reverberates from the far end of the valley. In those few milliseconds of aural transit, that small flitting bird may have already left the branch it was perched on when it gave voice to the sound that I perceive.

In April, Yuri and I were fortunate to be able to spend some time visiting temples on the Shikoku 88 circuit. Driving, not tramping the hard roads. Part of visiting each temple (we made it as far #36, in Kochi) is chanting the Heart Sutra.

This is a rather wonderful image from the eaves of Anraku-ji, #6. You may be familiar with the famous fundamentalist monkeys seen at Ieyasu’s garish shrine in Nikko. Here is strong evidence of more enlightened monkeys, deep in Japanese monkey counterculture.

Anraku-ji and monkey mind

Anraku–ji (安楽寺, the “Temple of Peaceful Relief”), is notable for, among many sculptural features, a long frieze wood-carving of detailed scenes from the life of Kūkai (Kobo Daish)i, including this incidental re-envisioning of the traditional image of three wise monkeys, Mizaru, Kikazaru and Iwazaru.

The Heart Sutra says:

Mu gen ni bi zesshin i mu shiki sho ko mi soku ho

—No eye, ear, nose, tongue, body or mind; no form, sound, smell, taste, touch, or mind object.

But what do monkeys know?

Seeking wisdom in the celestial persimmon orchard, these three aging monkeys have found a book, perhaps an exposition of the Dharma. Can they read it?

Who knows?

In some way they have awakened. Eager now to hear more, see more, and to debate more on the nature of wisdom, will they attain full enlightenment?

All things are possible.

The Heart Sutra also says:

Mu chi yaku mu toku i mu sho toku ko

—There is no wisdom, nor is there attainment, for there is nothing to be attained.

Monkey minds (like mine) love enigmatic wordplay.

Maybe the Heart Sutra was written (and translated) by monkeys?

Who knows?

Finally, a further reflection on openness, receptiveness:

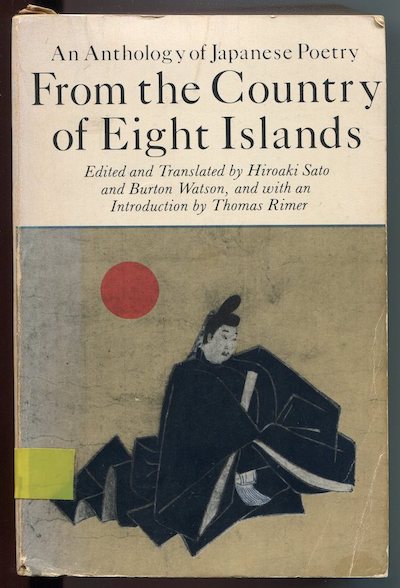

I’ve had this wonderful anthology of Japanese poetry, From the Country of Eight Islands, ever since a blockbuster ‘going out of business’ sale at Friends World College. Somehow, I only recently noticed that it was originally donated to FWC by a Kyoto nature poet, the one-and-only Edith Shiffert, who resided here for over 50 years, from 1963 until her death in 2017, at the age of 101. We recently included several of her poems in the Flora & Kyoto issue of Kyoto Journal, including this opening quote, from The Forest Within the Gate, Heian-kyo Media/White Pine Press, 2014:

With the entire earth

drenched in flowers and fragrance

why not peace and joy?

The book contains a typed postcard dated May 27, 1981, from Burton Watson, one of the translators, and had been sent out as a complimentary copy, in respect. I’ve heard the other translator, Hiroaki Sato, was a former student of Edith’s. I assume Edith had donated this volume when she was forced to dispose of possessions when moving with her elderly husband, Minoru, to a care home.

What makes this collection of translations most deeply meaningful to me, is finding Edith’s annotations, and especially the insertion of a simple bookmark in Thomas Rimer’s introduction. This means we can virtually read over Edith’s shoulder, notably where Rimer discusses the aesthetic of Yūgen, in which “a poem was intended to remain grounded in one level on a directly felt observation of nature, behind or beyond which some intimation of the existence of a different or higher reality was suggested.”

Rimer reminds us that this essential aesthetic embedding of nature in Japanese poetry (and vice versa) has in fact been transmitted through literary history to the present. It is easy to imagine Edith finding particular resonance in discussion of the place of nature in transcendent poetry. Writing was indeed her Buddhist practice. This meditative, essentially timeless and intensely personal embeddedness was evident in most of her work, including this poem, also republished in Flora & Kyoto, originally from her book In the Ninth Decade, White Pine Press, 2005:

Shinnyodo, Yoshidayama, Graveyards

This stone Buddha too

is circled with cherry blossoms.

The sky looks empty.Red camellias and cherry petals have fallen

over all the ground

and on the stone Buddhas.

Petals on my shoulders too.Temple roofs too high

for drifting cherry petals,

clear sky above them.In this vast graveyard

names meaningless, individuals nothing,

all their spent energies gone,

just ashes, of thousands from a thousand years,

quieted under the vast ephemeral space of sky

now knowing that much we fret about

is absolutely inconsequential.

Existence and beloved places, all vanishing.Grace, grace, afloat on that only

we are blown about gently

like these dispersed and vanishing

flower fragments.

Thank you for listening…

Ken Rodgers has been managing editor of Kyoto Journal since 1993, and a member of WiK since it originated in 2013.