By Nicholas Teele

Two of my favorite places in Kyoto are Yoshimine-dera and Sanko-ji. The temples are located partway up Shakadake, one of the mountains on the western side of Kyoto referred to as nishiyama (western mountains, 西山). Yoshimine-dera is famous for its beautiful ancient pine, its many blossoming trees, beautiful flowers, and autumn leaves. It is also the 20th temple on the Saikoku 33-temple Kannon Pilgrimage. Walking around the expansive temple grounds, with its various smaller temples, I always feel the “life force” of the place. Just beyond the north gate of the temple grounds is Sanko-ji. Both temples have a spectacular view of the city of Kyoto below, the hills and mountainsides of the eastern side of the city, and the areas to the south and southwest, but I actually prefer the calm of the smaller temple. And there, for a small fee, you can see some of the temple treasures and then enjoy a bowl of tea and a sweet in a quiet room with a perfect view.

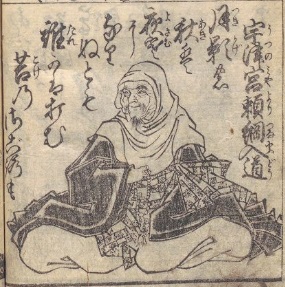

Yoshimine-dera was founded in 1042 by a high priest of the Tendai sect of Buddhism named Gensan. After a while, Gensan decided that he wanted a smaller place where he could concentrate on meditation, and in 1047 had a hermitage built on the north edge of the temple complex. Located within the folds of the mountainside in a small clearing at the edge of a precipice in a narrow valley, it was called Kitao Ōjō-in. Jien (1155-1225), a former Tendai archbishop, popular poet, and historian, was the third priest to live in the hermitage. In 1213, he passed it on to Zennebō Shōkū (1177-1247), an important early disciple of Hōnen’s who, at Hōnen’s request, had studied esoteric Tendai Buddhism with Jien. Shōkū, who is thought to have changed the name of the hermitage to Sanko-ji, is remembered today as the founder of the Seizan branch of the the Jōdo sect of Buddhism. (Seizan is an alternate reading of 西山). After Shōkū died, one of the most devoted of his many disciples, Jisshinbō Renshō, built a mausoleum there for his master, and a small hall for intensive meditation. Renshō’s secular name was Utsunomiya Yoritsuna (宇都宮頼綱), and this is his story.

In 1178 (or 1172), Utsunomiya Yoritsuna was born into a powerful Kanto warrior family from Shimotsuke in today’s Tochigi prefecture. The founder of the Utsunomiya family line was Sōen (1033?-1111). It is said that he was appointed head priest at the Futa’arayama shrine (in today’s Tochigi Prefecture) for service in wars further north. He was a warrior and also both a Shinto and a Buddhist priest. The third head of the family, Tomotsuna, is said to have been an officer in the North Side Guards, the elite military corps in Kyoto set up in the 11th century by Emperor Shirakawa to defend emperors and former emperors and their families in times of need. Tomotsuna is mentioned in that capacity in the Tale of the Heike, at the time of the late twelfth century wars between the Taira and the Minamoto. Tomotsuna’s brother Hatta Shiro was also an officer in the North Side Guards, and served in the Hōgen Disturbance of 1156, which involved two former emperors in a struggle for power.

The Utsunomiya family thus had established roots in Kyoto by the twelfth century. Yoritsuna’s residence in Kyoto was at the juncture of Nishikinokoji and Tominokoji; it is possible that it had been the family home since the days of his grandfather.

Yoritsuna’s father, not often mentioned in official records, is thought to have died when in his twenties. His mother is said to have been the daughter of Taira no Nagamori. He and his father were officers in the North Side Guards, similar to Tomotsuna. They, however, supported the losing side of the Hōgen Disturbance, and were executed by Taira no Kiyomori.

Yoritsuna, the fifth head of the Utsunomiya, is first mentioned in 1189 in the Mirror of the East (Azuma Kagami), the main historical record of the times we are concerned with. The record states he was introduced to the powerful leader Minamoto no Yoritomo following the Battle of Ōshū. He is mentioned again in 1193, when he represented his clan at the trial of Soga Tokimune, charged with the revenge killing of the man who assassinated his father.

In 1194, Tomotsuna was found guilty of appropriating public land. The punishment was exile, and Tomotsuna was ordered to Tosa, in southern Shikoku, Yoritsuna to Bungo, in Kyushu, and Tomonari (Yoritsuna’s brother) to Suo, in southwestern Honshu.

As his father was about to set off on exile, Yoritsuna wrote the following waka, poem number 444 in the Shinwakashū:

ゆく末も おぼつかなきを いかにして しらぬ山路を ひとりこゆらむ yuku sue mo obotsukanaki wo ikanishite shiranu yamaji wo hitori koyuramu With the future so uncertain how will you go on down unknown mountain paths all alone?

The poem contains an allusion to an earlier poem on setting off alone (Man’yōshū 2:106, by Princess Ōku).

二人ゆけど 行き過ぎがたき 秋山を いかにして君が ひとりこゆらむ futari yukedo. yukisugigataki aki yama wo ikanishite kimi ga. hitori koyu ramu Even when there are two people, the going is so hard, How then can you cross the autumn mountains all alone?

In 1199, the Azuma Kagami mentions Yoritsuna again, in a reference that has been taken to indicate both that the period of exile was over, and that he had assumed the role of head of the clan. His grandfather had retired to devote himself to the worship of Amida Buddha.

It is a sign of the wealth, and power of the Utsunomiya family that Yoritsuna’s three wives were the daughters of men who had been important in helping Minamoto no Yoritomo establish the Kamakura shogunate. Perhaps the most important of these was the daughter of Hojo Tokimasa. She was the half-sister of Masako, the wife of Minamoto no Yoritomo, the first Kamakura shogun, and the mother of the second and third shoguns, Yoriie and Sanetomo.

In 1205, in the midst of the unrest after Yoriie’s assassination, Yoritsuna was accused of plotting rebellion against the shogunate. The accusation had no real basis in fact and was probably made because Masako was involved in a power struggle with her father and Yoritsuna was considered by some to be powerful enough to be a threat.

To protest his innocence, Yoritsuna immediately took the tonsure and became a Buddhist priest. It is said that when he did, 60 of his retainers joined him. He wrote a letter refuting the charges and maintaining his allegiance to the shogunate. Charges were dropped. His action both assured the Kamakura government of his loyalty, and enabled him to continue to hold both his family’s lands and the areas then under his control. At that time he was in his late twenties. His his oldest son was too young to take over as head of the family so Yoritsuna kept that role until his son came of age. Yoritsuna’s name as a priest was Jisshinbō Renshō, and I will the refer to him as Renshō from here on.

In 1208 Renshō met and became a disciple of the famous Tendai priest Hōnen (1133-1212) who had been exiled from Kyoto for his advocation of the primacy of reciting the nembutsu (念仏 refers to the phrase “Namu Amida Butsu” which means ”I take refuge in Amida Buddha”). Renshō devoted his life to Pure Land Buddhism while continuing to write poetry, often with Teika or with his friends in Kamakura and Shimosuke, to performing tasks for the Kamakura government, and to looking after his clan until one of his sons was old enough to assume that responsibility.

Renshõ’s home in Kyoto was roughly at the juncture of Nishikinokoji and Tominokoji, not too far from that of the poet Fujiwara Teika, and the two of them became such good friends that Renshō’s daughter married Teika’s son Tameie. In 1222, she gave birth to a boy who was named Tameuji. Tameie later a major poet and took over as head of the family after Teika’s death in 1241. Their child, Tameuji, continued the styles and ideals of that line.

Renshō was living in Kyoto in 1221, when Retired and cloistered Emperor Gotoba reached out to him for support in a war against the Kamakura government. Renshō refused, and returned to Kamakura to join the inner circle of opposition to Gotoba.

Renshō the Priest

As mentioned above, in 1208 Yoritsuna met Hōnen, the founder of the Pure Land sect of Buddhism. At that time, Hōnen was living at Katsuoji, a temple located on a hill outside of Osaka, not far from the beautiful Minō waterfall. He had been exiled because of his religious activities, and was there waiting for permission to return to the capital.

The story is told that the first time Hōnen met Renshō he explained all four parts of the Sutra of Meditation on the Buddha of Infinite Life (Kanmuryōjukyō) [1] to the young priest rather than just the first part as he usually did when interviewing prospective disciples. Realizing Renshō’s seriousness, Hōnen accepted him as a disciple. However, in light of his own age, Hōnen soon introduced Renshō to one of his key early disciples, Zennebō Shōkū (1177-1247), with the request that Shōkū take over as Renshō’s teacher after his own death (which occurred in 1212).

From 1212 on, for over thirty years, Renshō served Shōkū. He was a serious student, and filled volumes of notes from Shōkū’s sermons. Unfortunately, it appears that only two of Renshō works are extant today: one is the Shakugakushō which is a record of part of Shōkū’s interpretation of the 7th century Chinese master Zendō’s Commentary on the Sutra of Meditation on the Buddha of Infinite Life (Kanmuryōjukyōsho). The other is Jutsujō, a record of Shōkū’s answers to questions posed by Renshō. Renshō often travelled with Shōkū, and actively supported the spread of the recitation of the nembutsu as the path to a pure active life and rebirth in the Pure Land after death. One notable trip took place in 1229, when they went to Taimadera, in Nara Prefecture. There, Shōkū identified the scenes illustrated in the Taima mandala [2] as being based on Zendō’s Commentary. Both Shōkū and Renshō had copies made of the mandala for use in the study the sutra and its meditations, and then distributed them to various temples.

In a moment of high drama, in 1227 Renshō and his brother (who had become a priest) joined a group which secretly moved Hōnen’s body to keep it from being destroyed by forces opposed to the new Pure Land sect of Buddhism with its central emphasis on reciting the nembutsu. Honen’s body was taken from Chion-in first to Nison-in in the Saga area of Kyoto and then on to a temple in Nagaokakyō later called Komyo-ji, where it was cremated. In the persecution of those who preached the primacy of the way of the nembutsu that followed, Shōkū escaped exile thanks to the efforts of Fujiwara Teika and others.

Renshō also participated both in founding and supporting temples. For example, he made large donation for the rebuilding of a gate at Mii-dera, in Otsu, and assured a supply of votive candles for the huge statue of Kannon Bosatsu at Todai-ji in Nara, a statue which had originally been commissioned by his grandfather.

After Shōkū’s death in 1247, Renshō built a mausoleum for his master and a hall for intense nembutsu recitation and meditation at Sanko-ji.

Renshō the Poet

Although focusing on Buddhism, Renshō’s was also an active poet who had studied poetry and written waka as a youth, and who continued writing poetry throughout his life. The depth of his interest in poetry is seen in his relationship

with his teacher, Fujiwara Teika (1162-1147) who, it is reported, mentions him again and again in his dairy, the Meigetsuki. It is not clear when Renshō’s friendship with Teika began, but probably it was at least by 1207.

In 1233, Renshō began construction on a home close to Teika’s in the Saga, roughly between Nisonin, and Seiryōji. Although the location is not certain, Teika’s villa was close by, and may have been at the site of the Enrian, which may also be the location of Tameie’s grave. In 1235, Renshō asked Teika to select and copy poems to put on the sliding doors in the new villa. The poems selected formed the basis for one of the most famous anthologies of classical Japanese poetry, the Hyakunin Isshu.

Renshō studied waka and wrote renga both with Teika in Kyoto, and with a circle of friends in the Kanto area. The latter group was known as the Utsunomiya Kadan. In Kyoto, he was part of a group of poets who gathered with Teika to compose waka and renga and he became acquainted with other poets such as Saionji Kintsune, Kujo Michie, and Fujiwara Ietaka. The latter joined Teika in writing poems for the family temple and shrine in Shimotsuke, Utsunomiya Jingū-ji.

Renshō’s standing as a poet was such that Fujiwara Teika included three of his poems in the Shinchokusenwakashū, an imperial anthology completed (1235), and over 30 of Renshō’s poems are included in later imperial anthologies. Further, his efforts as a poet and leader of the Utsunomiya poetry circle are seen in an anthology of poetry by members of the group, the Shinwakashū. The anthology contains 875 poems arranged in the order of the poems in an imperial anthology (poems by season, poems of love and longing, travel, etc.), and over 150 poets, including 18 women, represented. Renshō has the largest number of poems followed by those of his brother, Shinshō (Tomonari), who was an active member of the group and author of a poetic travel diary, The Diary of Priest Shinshō. [3]

The years between 1237 and 1247 brought Renshō much grief and pain. His brother died on the road, probably in 1237, and Fujiwara Teika, who was his brother-in-law and teacher of waka and renga, died in 1241. Then in 1245 his granddaughter died at the age of 15. As if that were not enough, in 1247 two of his sons found themselves on opposite sides of a violent power struggle. His eldest son, Tokitsuna, was on the losing side and committed suicide, along with two of his sons. Renshō’s other son, Yasutuna, fought on the side of the victorious Kujō. Then, finally, in the twelfth month of that year, Shōkū, passed away.

After 10 years of such loss, Renshō sought peace and quiet at Sanko-ji, and devoted the rest of his life to chanting the nembutsu, praying for the souls of the dead, and meditating. The following poem was perhaps written at that time. It is included in the 18th imperial anthology the Shinsenzaishu 『新千載集』poem nr. 507?) with the headnote “Written at his grass hut on Nishiyama.” It is the poem that was selected to represent him in the Hero’s Hyakunin Isshu (英雄百人一首) compiled in 1844.)

西山の草の庵にてよめる 月影の 秋は夜寒に なりぬとも 誰かは打む 苔のさごろも tsukigage no aki wa yosamu ni narinutomo tare ga wa utamu koke no sagoromo though autumn’s moonlit nights have become cold, who is there to pound & soften my moss-patterned robes?

A party was held for Renshō when he turned eighty, and the contributions of waka by guests are recorded in the Shinwakashū.

Renshō died in 1259; some of his ashes were buried in a small cemetery at Yoshimine-dera beside those of Shōkū, and some were interred in the family temple in Shimotsuke. His son Yasutsuna had years earlier assumed the role of the 6th clan head, maintained the family position in society and passed it on. The power and influence of the Utsunomiya was to last for over two centuries.

Note: Among the many materials that I have used for researching this piece, especially useful has been Kajimura Noboru’s Utsunomiya Ichizoku (梶村昇『宇都宮一族』東方出版, 1992).

Footnotes

1 観無量寿経. The character ‘kan’ (観) in the title has also been

translated as ‘contemplation’ and ‘visualization.’ It refers to

intense concentration on an object or scene. The sutra contains

thirteen meditations, followed by three more categories which are

usually included as meditations, for a total of sixteen.

2 当麻曼荼羅. An excellent discussion of the Taima mandala,

including an account of Shōkū first seeing it, and his and Renshō’s

efforts to have copies made and distribute them, is in Elizabeth ten

Grotenhuis, Japanese Mandalas: Representations of Sacred

Geography (U of Hawaii P, 1999.) Renshō is referred to as Jissōbō,

on p.128.

3 Translated by Herbert Plutschow and Hideichi Fukuda in Four

Japanese Travel Diaries of the Middle Ages (Cornell University East

Asia Papers No. 25, 1981) pp. 45-59.

*********************************

For an interview with Nicholas Teele about his unusual past, see here. You can also view his writing about Emperor Sutoku in Kyoto, or the 13 Temple Kyoto Pilgrimage, or a ‘reborn’ Kyoto Pilgrimage. For a list of his publications, see here.

Recent Comments