REVIEW by Rebecca Otowa

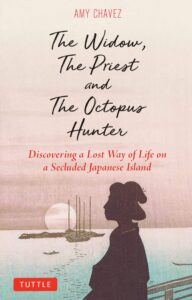

THE WIDOW, THE PRIEST AND THE OCTOPUS HUNTER

By Amy Chavex (Tuttle 2022) Available on Amazon

Amy Chavez has had an unusual life in Japan. Beginning in a teaching position in Okayama, a city between Kobe and Hiroshima, she moved to an island in the nearby Japan Sea known as Shiraishi (White Rock) Island, where she has now lived for a quarter of a century. She is a familiar figure on the island, along with her husband Paul, living near the port and operating the Mooo Bar, a little café right on the beach, with a sandy floor and rough wooden tables, catering to the dwindling tourist-and-beach-lovers’ trade.

This latest book of hers is a labor of love which has been in the making for many years. With a population of only 430 souls (at the time of writing), mostly old folks, Shiraishi is one of those rural communities destined to disappear with this generation. Before that happens, Chavez has made it her mission to record the stories of many of these people. The result is a book that is not only a valuable peek into the lives of Japanese in the last century, but also a very entertaining read. Each story is so different that I won’t pick up individual ones here, but try to convey a general idea of topic and feeling.

The book is redolent of one of Japanese culture’s several ground notes, the ocean. There is a wonderful sea tang in every word. Those of us lucky enough to have experienced at first hand this island, or indeed any slightly down-at-heel Japanese seaside community, will immediately be able to picture the scenes she shows us. These are places of weathered wood buildings facing the sea across a narrow road; plastic buckets, nets, and floats piled up against the sides of houses; ferry boats with chains and ropes, and rust showing through multiple layers of white paint; large geometrical concrete blocks spilled across the beach like a giant child’s toy construction; smells of fish, salt and seaweed from the catch spread out or hung up to dry everywhere. On Shiraishi these images are augmented by the inland communities surrounded by rice fields and vegetable patches, the shrines and local gods immortalized in stone markers, and the seaside quarries on the other side of the island, which provided its name back in the days when the prized “white stone” was cut and carried by boat to build castle walls and other lasting structures far away.

Amy talked to many residents of the island, recorded the conversations, translated them, and worked them up into some thirty vignettes telling their stories. Truly a long and, I imagine, deeply satisfying project. There are some story arcs that span the entire book, but I won’t give these away here, preferring to let readers discover them for themselves.

If you wish to know more of Amy’s own story, the Foreword, Introduction and Epilogue, as well as the penultimate story, “The Foreigner”, talk about how she felt on experiencing such an island community for the first time, and the twists and turns in the road as she gradually accustomed herself to it. And it to her. Her description of the local authority who decides which “people from elsewhere” (yosomono) will be allowed to take up residence here, was striking to me. The culture would definitely be vulnerable to “undesirables”, especially perfect strangers with no relatives or family ties to the place. (The author herself was looked at askance in the early days, as she describes, for loud barbecue parties and blaring music in front of her house.) At the same time, depopulation threatens to put paid to centuries-old traditions. This dichotomy of needs – the economic need for “new blood” versus the need of the residents to exist quietly in familiar, traditional surroundings – is felt in many rural communities throughout Japan, but the very isolation and insularity of this place as she describes it make the situation here particularly precarious and disturbing. The island residents probably see their situation as symbolized by the danger of the giant boulders dotting the hillsides, poised to come rolling down onto their houses, as indeed happened to Amy herself (“The Foreigner”). These people live between a (white) rock and a hard place, neither of the two choices of the dichotomy of needs being feasible for more than a few more years into the future.

Like many of us, she wonders what the next years hold in store. “Those previously dedicated to evening strolls along the road… have gradually bent over like rice heads at harvest time. I’ve watched my neighbors’ flawless skin furrow to deep wrinkles, and I know they must be observing the same in me.” Not only do aging rural people have to contend with the indignities of their years, they also have to cope with the sadness of cultural discontinuity – the neighborhood will not continue when they themselves die, a continuity which used to be the reassuring norm; the future is a blur of unfamiliar sights, customs and materials, with no one to mark and remember their lives of hard work and faithfulness to the old rituals and traditions handed down from time immemorial. It’s really heartbreaking, though probably inevitable. I myself live in such a community and family, I myself am aging and have watched my neighbors age. Our children have escaped to wider horizons and more choice; the continuity of centuries is breaking up. My own house, 350 years old, is one of only two of that vintage left in our area. The structures may endure, but the lifestyle they were built for will not, as they are increasingly demolished outright or at best taken over by people who have no connection to the land that spawned them.

But I digress. For me the value of Amy’s wonderful collection of stories lies here, that these tales of real human beings have been lovingly collected and preserved in this form. We too may enter into their lives and experience what they felt to be important, from carefully maintained octopus pots and fish nets to wedding photos and kimonos in drawers that immediately evoke memories of occasions and dances. The people in these stories aren’t just quaint puppets dancing for our pleasure. Personal idiosyncracies, sufferings, and joys abound; they could be the inhabitants of any human community of the past 300 or so years. At the same time, their world has been even more traditional and slow to change than mainland communities, and each small detail of their lives has been preserved here for us to enjoy, savor, and ultimately, sigh over. It’s a book that breathes of the sea and those who make their living on it, and a unique relationship to the pullulating life of “over there” (the mainland). One comes away happy to have made the acquaintance of these strong, no-nonsense souls. At the same time, one feels the melancholy of inevitable endings.

Thank you, Amy, for writing a book that allows us to feel these things by keeping a vanishing culture safely cupped within these pages as in an octopus pot.

There is a fascinating section with old photographs, and also lovely line drawings by Okae Harada.

Recent Comments