A traditional Japanese neighbourhood is a lot like a small fiefdom; it rolls with its own rules and rosters, elects its own committees, demands that its denizens perform seasonal duties such as river cleaning and shouldering a portable Shinto shrine at festival time, and is usually presided over by a big kahuna and his/her sidekick, a treasurer.

Acceptance to the ‘fief’ requires of newcomers only two things: that they don’t behave strangely and that they abide by the rules. This means paying your annual festival fees, taking your turn with the orange flag at the school crosswalk, supervising the garbage corner, not playing Meatloaf up loud on hot summer nights or UB40 (with a woofer) when the red wine goes to your head.

Having lived in Himeji for over two decades now, I’ve come to realise the value of rules and systems; not only do they create a clean and secure environment in which to live, but they encourage neighbours to connect with one another.

When I first arrived in the Good Hood, I knew not a soul. Now, eighteen months later, I have this to report:

To the south of me lives the Truckie: a small, bow legged man with a smoky baritone voice who trots his two shitsu dogs around the block each morning at dawn; then, at seven a.m., revs his four-tonne Hino with its rice harvester mounted on the back, bids me a gravelly good morning and departs for the paddylands upcountry. His wife is nice too; she comes and goes on her 50cc Honda scooter, tends to her azaleas, and passes over the fence seasonal goodies such as bamboo shoots in autumn, leeks in winter, and bitter melon (goya) in summer.

Next to the Truckie resides the Tinkerer, a man who believes seven a.m. on a Sunday is the best time to fix something—anything! Then, as the morning eases into lunch hour, the whine of his power tools fades into the sounds of SuperTramp, Janis Joplin, David Bowie et al, and he steps from his shed to ponder his fig trees for as long as it takes to smoke a cigarette. He gave me a clump of moss as a welcome present.

Behind my house lives the Gardener, an elderly man whose bonsai scissors snip back and forth across vines of jasmine and clematis all summer long. Around dinner time, when I’m still looking out my rear window for writing inspiration, I glimpse an arm reach from his window to pluck a few fingers of red okra. He has inspired me to turn my own front yard into a kitchen garden, to weed it and reap!

To the north, facing the rice field at the end of the street, lives the Launderer, an elderly woman whose house has withstood many a typhoon and earthquake—but only just. Through its cracks and gaps waft the aromas of sandalwood incense and mosquito coil. She appears in the mornings to hang out her laundry, then retreats to a darkened living room from behind whose curtains will come jolly laughter and the white noise of the TV variety shows for the rest of the day. I gave her a bagful of tomatoes from my garden this summer, and the next day she delivered a dozen onsen-tamago (hot spring boiled eggs) to my door.

Across the road live the Spinsters, two elderly sisters who sleep upstairs with their lights on–or perhaps they don’t sleep. A Black Cat delivery truck stops outside their house every afternoon and the driver passes a mysterious package to waiting hands inside. It all seems very Hitchcockian, but I’m sure there’s a logical reason—medicine, foodstuffs, bandsaws, bleach, chisels … I might borrow my son’s binoculars, wait till midnight.

Every neighbourhood has its teachers; mine has an abacus teacher, an ikebana (flower arrangement) teacher and an English tutor. But by far the busiest sensei on the block is the woman (also the neighbourhood big kahuna) who teaches violin and piano. She lives in an expansive wood and tiled-roof house on the corner of my street. Throughout the hot summer months, I have watched the moon rise over her rooftop, hoping to hear Flight of the Valkyries or something from Carmen, but getting off-key Debussy or a little wobbly Chopin to go with my Kirin lager. Unlike the Spinsters, her deliveries are not suspicious—mostly kids with Coke bottle glasses in private school uniforms, packing violin cases and satchels of sheet music who are delivered in Mercedes 4WDs and black Lexus town cars.

When they’ve gone, and the evening calm has crept back, a tall, knobby-kneed white man might be seen standing outside her door. He holds a small bag of cherry tomatoes in his hand—a peace offering for the previous night’s Meatloaf up loud—because, he says apologetically, the red wine went to his head again.

**************

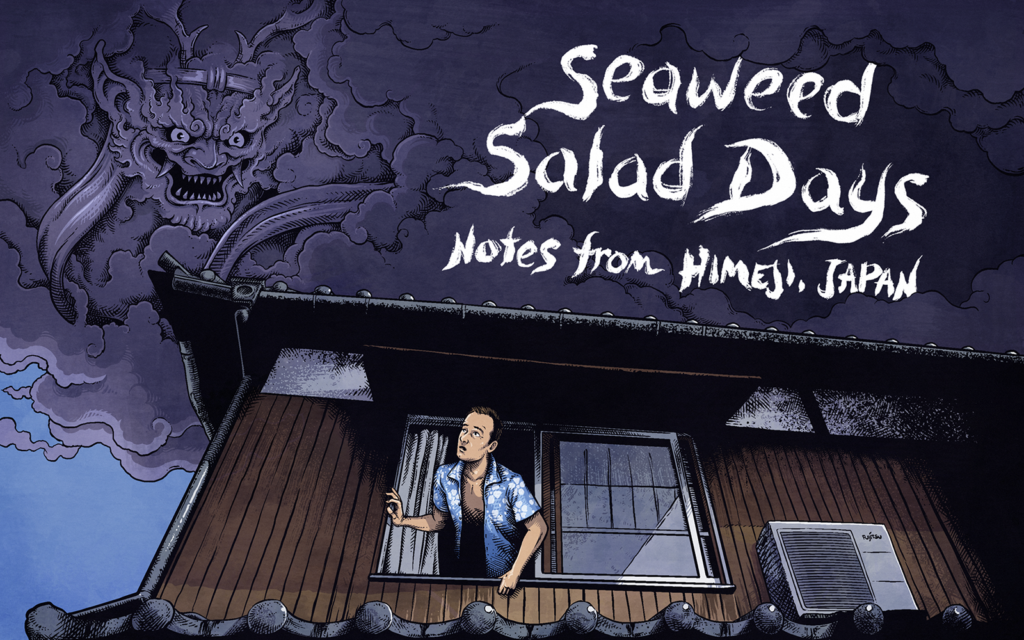

Read more Seaweed Salad Days posts from the Good Hood.

Read Simon on marketing, or a piece about Greenhouse Blues. Also see Oysters to Die For or Hyogo Vignette.