About twenty years ago, walking down Teramachi-dori from Shijo, I came across a musty little shop specializing in pre-Meiji wasōbon (books printed and bound in the traditional Japanese manner). Among them, I found a slim rather-worn and weathered book which was titled Kannongyō Hayayomi eshō, which roughly translates “An illustrated ‘fast read’ of the Kannon sutra.” The sutra is part of the Lotus Sutra (the 25th chapter) and has become so popular that it is often printed independently.

Kannon (Chinese: Guan Yin, Sanskrit: Avalokiteśvara) is one of the most loved of Buddhism’s many buddhas and bodhisattvas. A bodhisattva (bosatsu) is a being who has attained enlightenment but refused final entry into nirvana until all sentient beings are saved, and Kannon is a bosatsu who represents the path of compassion to that goal. Kannon can thus be seen to represent an ideal, concept, or Way.

The Heart Sutra (Hannya Shingyō), the sutra more often translated into English than any other, is Kannon’s highly condensed summary of higher Buddhist wisdom (prajna paramita) regarding the nature of existence. At the same time, Kannon is a miracle-working divinity. The Kannon sutra is devoted to a description of the role of Kannon as the one who hears the cries of the world. The sutra encourages devout believers to call out the name of Kannon in times of great need, and includes many examples of ways and forms that Kannon appears to the devout in order to save them. In Japan, stories of miracles performed as a result of such worship of Kannon go back to the ninth century Nihon Ryōiki (Miraculous Stories from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition) and there are hundreds of temples across Japan where Kannon is worshipped.

One of the most well-known, and oldest, pilgrimages in Japan is the Saikoku Sanjūsansho (the name is sometimes expanded to Saikoku Sanjūsansho Kannon reijō junrei). It is a pilgrimage to 33 temples in the Kansai area where the principle religious focus is on Kannon. Believed to date back to the mid-Heian period, the pilgrimage is so influential that it has inspired similar pilgrimages to Kannon in different areas around Japan. The most well-known of these are the Bandō Sanjūsansho and the Chichibu Sanjūsansho, both in the Kanto area. Because at the time I found the book I was in the midst of making the Saikoku 33 pilgrimage, my interest was immediately aroused, and I bought it.

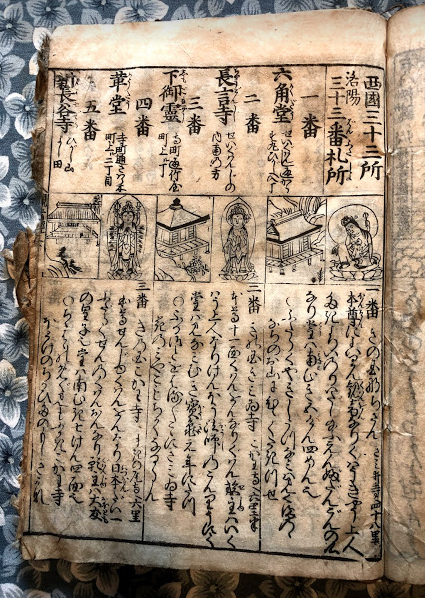

Looking through my newest prized possession when I got home, I saw that it was an undated edition of a book originally published in 1739. Following the condensed and illustrated version of the Kannon sutra was a list of the 33 Saikoku Kannon pilgrimage temples, with little pictures of each temple and its statue of Kannon, along with a bit about the temple, and the poem (goeika) for it. There were also lists of 33 Kannon temples in both Rakuyō (Kyoto) and Osaka. Fascinated by my discovery, I decided that someday I would make the Kyoto pilgrimage. This was my introduction to the Rakuyō Sanjūsansho Kannon Reijō Junrei, or pilgrimage to 33 temples in Kyoto where Kannon is worshiped.

Initially, I was unable to find much information about it, but that didn’t stop me from deciding to make the pilgrimage. For major pilgrimages such as the one to 88 temples on Shikoku and the Saikoku 33 pilgrimage mentioned above, there are books to record the visit to each temple, called nokyōchō. These books are printed with the name of each temple, its Buddhist sect affiliation, the main buddha or bodhisattva, and the poem for the temple. When a serious pilgrim visits one of the temples he or she prays and recites the mantra for the buddha or bodhisattva, the poem for the temple, and perhaps the poetic summary (ge) at the end of the Kannon sutra, or the much shorter Heart sutra and then gets the book stamped and written in by a priest or layman working at the temple.

As there was no nokyōchō for this pilgrimage, I bought a blank book and added the names of each of the temples in numerical order. However, I quickly discovered that some of the temples no longer exist. In the case of Yoshida-dera, for example, the shrine is still there, but the temple is gone, and the statue of Kannon which had been in the temple is on display at the Kyoto National Museum. As a result of lack of information and an increase in administrative duties at the school where I worked, my progress floundered, and simmered on a back burner until I retired several years ago.

Returning to it, I discovered to my delight that the Rakuyō pilgrimage had been ‘reborn.’ An internet search turned up a joint guide to the Saikoku 33 pilgrimage and the Rakuyō 33 which had been originally published in 1687, and had been republished in 1986, using modern type. There was a paragraph or so about each of the Rakuyō temples (those that were also on the Saikoku pilgrimage were directed to the entry for the temple in that commentary). The contents made it clear that in the seventeenth century some changes had been made in the original pilgrimage. I further learned that in 2004, the pilgrimage had been revised once again, omitting those temples no longer in existence and adding others to bring the number back to 33. In 2019, the pilgrimage celebrated the 15th anniversary of its second “rebirth,” and 355 years since its first.

The origin of the Rakuyō 33 pilgrimage may date back to the emperor Goshirakawa (1127-1192). He loved pilgrimage and is said to have gone to the major Kumano shrines in Wakayama over thirty times. He ordered that soil and foilage be brought from three of them and founded three Kumano shrines in Kyoto, for those who could not go all the way to Wakayama. Goshirakawa is also said to have had 33 temples in Kyoto designated as a pilgrimage circuit to Kannon, for those who could not make the Saikoku pilgrimage: the Rakuyō 33. This is the standard story of the origin of the pilgrimage; however, the introduction to the 1687 guide to the temples gives the date of 1431 for the start of the pilgrimage, during the reign of the emperor Gohanazono.

Over the last year and a half, I finally made the Rakuyō 33 pilgrimage, going once a month or so to three or four of the temples. I made the walks with a good friend, also retired, as part of a plan to get out and visit historical and religious places in and around Kyoto. (Our wives were happy to have us out of the house.) For the Rakuyō pilgrimage, we usually adapted one of the recommended walks in the two current guidebooks. These books list four walks, grouped by geographical proximity rather than numerical sequence. One of the guidebooks, Kyoto Kotokoto Kannon Meguri, Rakuyō Sanjūsansho Kannon Junrei, includes the names of nearby restaurants.

A majority of the 33 temples are located in the central and eastern half of the city, but other parts of Kyoto are also included. For example, one of the temples is at Mibu-dera, another is a temple originally part of Kitano Tenmangu and located near the torii for that Shinto shrine, and the Kannon-dō at Tō-ji is also on the list. Considered in numerical order, they make a very rough circle, starting with the Rokkakuō, heading east, then north, then south, west, and north.

Some of the temples are well known, such as the Sanjūsangendō. Some are sub-temples within the precincts of larger temples. For example, Kiyomizu-dera has several, and Shin Hasedera is part of the Shinnyō-dō. Some appear to be rather well off, but the majority do not show any sign of opulence. Some are not open to the public, although it is possible to get one’s nokyōchō stamped and signed. Others are open and friendly, and may even give you a cup of tea. Nearly all appear to be active in their communities. We often saw one or two other people making the pilgrimage, and were told that the number of people the Rakuyō pilgrimage is increasing. We met one young lady who was making the pilgrimage for the third time. In addition to being a good way to see the city of Kyoto, the pilgrimage provides a fascinating picture of urban Buddhism, and of Kannon.

I had already visited quite a few of the Rakuyō 33 temples, but there were some delightful surprises. One was Chōraku-ji. Located up past Gion and Maruyama park, it is a quiet temple, with a garden created by Sōami (who also designed the garden at Ginkakuji) that is exquisite and reverberates with the aura of past centuries. It is the temple where Taira no Tokuko (1155-1213) the daughter of Taira no Kiyomori, empress to the emperor Takakura, and mother of the emperor Antoku, took nun’s vows following the fall of the Taira and death of Antoku, still a young boy, who drowned at Dan no Ura in 1185. Known as Kenreimonin, she later went to live at Jakkō-in. Whereas most of the temples are clearly in the city, Chōraku-ji is just far enough away to provide a pervading atmosphere of beauty and calm. (The picture of a stamp and sign below are for this temple.)

Links

- The URL for the Rakuyō pilgrimage is http://rakuyo33.jp

- The URL for a page in English which lists the temples and has two maps is: https://rakuyo33.info

- The URL for the Saikoku pilgrimage is: https://saikoku33.gr.jp

- For an interview with Nick Teele about his life, see https://writersinkyoto.com/2018/07/nicholas-teele-interview/

References

- 観音霊験記研究会,「西国洛陽三十三所観音霊験記」『駒沢短大国文』Vol. 16, Nr. 35 (March 1986) pp. 35-83.

- 『京都ことこと観音めぐり 洛陽三十三所観音巡』京都新聞出版センター,

2006. - Nakamura Kyoko, tr. Miraculous Stories from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition, The Nihon Ryōiki of the monk Kyōkai. Harvard, 1973.

- 『洛陽三十三所観音霊場巡礼』平成洛陽三十三所観音霊場巡礼会, 2017.

- —-. 『観音経早読絵抄』Undated edition, originally published in 元文四年(1739).