WiK member Ken Rodgers (Managing Editor of Kyoto Journal ) writes…

With the 75th anniversary of D-Day currently in the news, I was reminded of WiK’s Battle of the Somme reading a few years back, where I shared excerpts from my maternal grandfather’s grim war diaries describing trench warfare. Another book that has great personal significance for me was written by my father, completed just a couple of months before he passed on in 1988, about his time as an RAAF Lancaster bomber pilot in England towards the end of WWII. Title: There’s No Future In It.

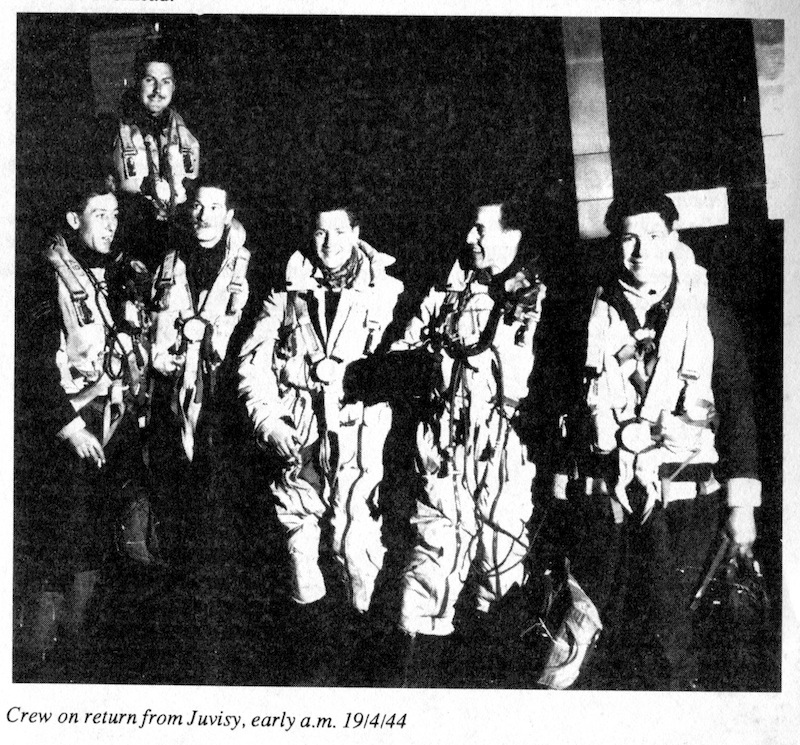

My father flew 32 mostly night bombing operations (a ‘tour’ of ops), from East Kirkby in Lincolnshire. By age 23 this former farming lad was a Flight Commander. After finishing his tour (facing many other perilous situations in addition to those excerpted here), he became a test pilot – another dangerous occupation. From his book it’s clear just how truly fortunate he was to survive, and by extension, how I myself, my two sisters – and our sons and daughters too – might so easily never have existed…

{RAAF – Royal Australian Air Force]

**************

Excerpts from There’s No Future In It

by Wade Rodgers, D.F.C., ex-R.A.A.F.

Dawn on June 6 1944 saw the long-awaited Invasion of Europe in the Caen area of Brittany.

In the early hours a thousand bombers flew carefully in a wide arc around the cross-channel invasion fleet and knocked out all ten coastal defence heavy gun batteries ahead of them, so relieving the incoming boats of a lot of resistance. Of course we were almost certain that This was It and had confirmation when we flew back empty and, still in the dark, had a look at the H2S cathode plan indicator showing the immense spread of shipping on its way south. It was an historic day and we felt we were doing our bit in the monumental task of getting the troops ashore. But we hadn’t finished yet. Late that evening we were back again to bomb rail and road intersections in the Caen area ahead of the invasion, to prevent the arrival of German heavy armoured vehicles and tanks. Our attack was made under cloud from about 2500 feet for accuracy, too low for photos.

Three nights later we went to Etampes, just south of Paris. I can’t remember the target and the photo wasn’t clear. On 24 June we did our eighteenth trip, to Pommereval. This was another railway target in France to prevent the movement of troops and equipment forward from Reserve positions towards the invasion coast. Numerous smallish numbers of aircraft were detailed from our Group and others to cover the network of vital rail and road links over the next month or so.

On the night of 27 June, we went at high level to a major “Doodlebug” or V1 storage and discharge site at Marquise Mimoyecques. We got a good target photo but heard later that the main dump had a concrete roof of such strength that our one thousand pounders would have had no effect.

Since they first appeared on June 12, the VI flying bombs had proved to be pretty destructive over southern England. They had, I think, solid fuel which was converted and blasted out the back. Thus the monster was “jet-propelled” for the metered amount of fuel, whereupon propulsion stopped and vanes tilted it down, to explode on point of impact. The thing weighed about a ton and flew from sites on the close French coast, aimed and timed to reach London as a primary target. Speed was in the order of 450 m.p.h. and only fast fighters could keep up, so special techniques were evolved. By these, either they were shot down or, in some instances, a fighter pushed a wing tip up under a bug’s wing and upset its gyroscopes, sending the thing into the ground, preferably in open country.

4 July. 20th op. to St Leu d’Esserent. This was a railway complex (with a branch leading off to V2 storage in mushroom caves at Criel, which we visited later.) Aiming point photo yet again. Our photos prove we bombed targets.

On 13 July we had a long trip down the South East of France at a low 5,650 feet, to knock out a great intersection of railway lines at Culmont Chalindrey. On the way down we watched a raid on another target off to port. First flares then markers and then red and green target indicators in a cluster. Right on schedule the main force let go with the lot for fifteen minutes. Real copybook stuff. Ours went off as well and we got the now almost inevitable photo of the centre of the yards.

Two nights later we repeated the performance at Nevers, which I think was in the same area. Another second dickey rode with us and we gave him the usual gen, showed him the pretty lights on the ground and took him through the ugly ones at our own level. P/O Sargeant was impressed. I think that on this night we passed through a long gloomy patch of Nimbostratus cloud, both coming and going. Next to Cu-Nimbs and their thunderheads, this is the worst cloud, being amorphous and dark, with no visible horizon even in daylight. In this lot there was the usual freezing rain and icing, but worst of all was the St. Elmo’s fire which flickered from the edges to the centre of the cockpit canopy and windscreen and also the turrets, blinding us and probably all the other crews in the aircraft stream.

Yes, the weather was often as troublesome as the opposition and the two together made for bad relations! And yes, again, there were far too many collisions than was healthy. Always, aircraft were turning short or overshooting or just drifting through the stream and we were always on the alert for them. At a distance at night there seemed, at first, very little difference between friend or foe. A lot of gunners, trigger-happy and lonely in their turrets hour after hour, shot first and asked questions only if there was anything still in sight.

Here I might mention weaving and banking searches. On the first trip, with Rogers, I was appalled to see him use the auto-pilot for long stretches, even over Germany. Some Squadrons encouraged its use but I always swore I never would, and in fact never did, engage the thing, even on the final long trek to Konigsberg of 10 hours 40 minutes. You see, there were always those two seconds to disengage it and I wanted those two seconds to start evasive action when necessary. Also its use discouraged banking searches which put the aircraft almost on her wingtips so that the gunners and others could look deep down below us, always the dangerous black spot, not normally visible to them.

After the war we were astounded to learn that some bright gun enthusiast of a Luftwaffe mechanic had hatched up a rig for mounting two upward firing cannons, 20mm or larger, in the roof of a JU88 twin-engined night fighter and, ultimately, in the more efficient Messer-schmitt210. With their own radar, and being vectored into a stream of our bombers, they could latch onto one and come up behind and below. They then moved right in under the bomber’s belly and lined up the cannon on the starboard main fuel tank between inner engine and fuselage. One rapid burst and they dropped smartly away to avoid the inevitable fire and explosion or wing burning off. One ace pilot has been credited with some 160 kills in this way and on one night downed six Lancs in 30 minutes. Two PFF [Pathfinder] types were flying along side by side in formation when an Me210 came up and knocked down one of them. The other didn’t seem to notice he was alone and followed his mate to eternity two minutes later. One crew member survived and told the tale.

I was always wary of this blank spot underneath, even though I didn’t know of this enemy invention, which they called Schrage Muzik — Jazz Music.

“Weaving” was officially frowned upon, in fact, forbidden. There was increased danger of collisions in the Stream, obviously, and it was not conducive to orderly navigation. Jimmy and I talked this over and experimented with gentle weaving over a given distance, noting the slightly longer travel time from A to B. I did a weave that evened out over a distance, being neither regular nor pronounced. The result was a variation of directional flying, by which radar predictors for flak batteries might be foxed. Also, as we saw later, fighters would come up, have a look from well back and, deciding that this bloke was awake, slide off in search of an easier victim. We’ve actually seen this happen and a stream of tracer putting paid to an adjacent Lanc.

18 July. D-Dog to Caen with 13,000 lb. at 12,000 feet. This was a famous raid in which a thousand Lancs and Halifaxes dropped the load at daylight on the German troops preventing the Allied breakout from the beach-head. It was a most intensive raid and we got no photos through the pall of dust and smoke that arose.

After our bombing run, we came around to starboard and spent some time having a grandstand view of the landing operations, the “Mulberry” harbour and the mass of shipping pouring in materials to the shore.

The next day we did a second daylight raid, to Criel Thiverny at 14,300 feet, too low for a daylight, we all agreed. This was the mushroom cave complex in which were stored the V2 rocket bombs, fiendish things which were launched almost vertically and reached a speed of some 3000 m.p.h. on the downward path. I had had experience of these in London one early morning, after travelling up from Plymouth. I’d gone into the station, bought a cup of tea and was just about to sip it when there was a resounding bang somewhere nearby, followed by the whistle of this V2, which had travelled faster than sound. I didn’t stop to enquire but took the next train North out of London.

On this fine afternoon in July, we arrived over Criel Thiverny and everything was laid out below. Somehow Fred was not happy with our run-up, even though we were in the Stream, and I was horrified to hear him say, “Dummy run, go around again.” Instead of grabbing the emergency bomb release and letting them go, I did just that, went round again.

There, completely on our own, we made another run-up on the tunnel entrance. The 88mm guns had gone silent and all was peaceful as we dropped the load. Seconds later, and I wonder now why the gunners waited so long till the bombs had gone, a box barrage of 88mm shells burst all around us. From the upper turret, Frank shouted, “We’re hit!” over the intercom. No thought of the camera run, now half over, was in anyone’s mind. I slammed the wheel and rudder hard over and went into a screaming dive to starboard. Even in the heat of the moment it was instinctive to go starboard, as I’d drilled myself for such an occasion — the Germans thought all British pilots turned port, as in a circuit of an English airfield. The next box barrage, which took twelve seconds from the ground at this height, arrived just where we would have been, but we were now screeching back around to the west and all taps were open in our hurry to get out of that place.

The Stream of Lancs were mere specks in the distance and we had no hope of catching them. The fighter escort covering the operation at 30,000 feet would be on their way back as well and we were on our Pat Malone. There was little conversation till we reached the coast in record time. By luck we went over no more flak batteries and not one fighter appeared — a flight of Messerschmitts could have made mincemeat of us. I still have the last camera photo — oblique to the left

There was one flak hole through the fuselage wall and the chunk of hot metal was imbedded in the ammunition trays to Frank’s turret, below his feet. How lucky we were — I hope even Fred the Atheist said a little prayer of thanks to Someone.

These daylight ops. were frightening things. One felt so exposed — we could see the ground and the gunners down there could see us no doubt, if they weren’t glued to their radar predictor screens. Certainly they would have been aware, in this case, of an aircraft doing a run over the target alone and our height of 14,000 feet was in very easy range. They could, in fact, fire accurately at well over 20,000 feet, tracking us with radar and with fuses set to our height. At night we felt hidden in the dark and even the flak bursts were a quick flash and the smoke merged with the background. In daylight the bursts left small black “mushrooms” of smoke writhing and curling in the air; a barrage from six to eighteen guns at close range around us, as we flew in on the bombing run, gave the impression of an inescapable barrier. With multiple “boxes” stretching ahead there was a strong natural urge to swing away, away anywhere except the place where they expected us to be. But, as gaggle leaders, we couldn’t be seen to waver and we just had to plough on through it, with a prayer wrung from the heart…

“… Lord help us… we can’t help ourselves…”

On the night of 24/7, we went to Donges, St. Nazaire, in S.W. France, to do something about U-boats, I think. Oil storages? That wasn’t our worry.

LE-D for Dog was far ahead of the Stream this time, far ahead of the Pathfinders, thirty minutes ahead in fact. Jim Campnett had been detailed to get a three-drift wind and get it radioed back to Command pronto so that it could be passed back to PFF and Main Stream for bombing. To do this we fixed our starting point by Gee, one of the Nav aids in use in short range of transmitters in England. Then I flew a smooth triangle of equal length and Jim found the wind drift from our old to the new ground position. “Right, whizz this off, Tommy”.

Thank goodness we got that done for, a matter of minutes later, searchlights stabbed out of the darkness and pinned us against overhead cloud. Up, too, came the flak to our 8,300 foot level and there was a twang as something hit us. At this height the searchlight cone was very broad and escape sideways would have been long and dangerous. Suddenly I stuffed the wheel forwards and LE-D screamed earthwards.

Too sudden for the searchlight boys, we shot into darkness and I tried to pull out of the near vertical dive. Nothing doing. Heavy with bombs, she reached 420 m.p.h. — that is, 60 m.p.h. above safe speed empty. Jack lent his weight to the wheel and I used trim tabs to ease her slowly back and upstairs again. In the nose, Fred swore he saw the ground rushing up at him and we were all shaken by the scrape with death. (Years later, a boffin worked it out for me and estimated that we were 2,000 feet underground on our pull-out!)

Nothing loth, we then had to nip smartly out and swing into the Stream as they followed a known track over Donges. I did this merging back into a bomber stream at other times through the tour and believe me, it’s not a pleasant thing to do with “kites” whizzing past you on the turn. However, we bombed and got our photo. Jimmy got a Mention in Despatches for his wind, which was spot-on and made the raid a success.

The homeward run was not a happy one. Something was wrong with our main hydraulics and we soon found out what it was — there was no oil pressure to the system — no brakes, no flaps, no undercarriage, etc. We found afterwards that a chunk of flak (it’s now in the drawer of my desk) had entered the leading edge of the starboard wing between my cockpit and the inner engine and had torn through three of the six hydraulic lines, to become embedded in the main wing spar.

Landing in no-wind conditions and without flaps and brakes, (Jack had lowered the wheels with the emergency air system), I ran on through the boundary fence and came to rest in a paddock of hay stooks! The Group Captain came charging out in his car, demanding to know the Captain’s name, but he changed his tune when Bert leaned out of his turret and told him who it was and the circumstances. We all had a laugh about it when we got in to de-briefing.

The Lancaster

A total of

7,377 Lancasters were built and 3,345 were lost in action. They flew 156,318

sorties and dropped 608,613 tons of

bombs.

Vital statistics: Wingspan 102 ft. Length 69 ft. Height 20 ft. Engines 4 x 1,460 h.p. Rolls Royce “Merlin”. Weight empty 36,900 lbs. Fully loaded 68,000 lbs.

Cruising speed full loaded — normally kept at 160 m.p.h. indicated airspeed for optimum performance, which seemed slow when the enemy were shooting at us! Actually the 160 m.p.h. at 20,000 feet with allowance for atmospheric temperature and pressure, could be 210 m.p.h. true airspeed and, with a following wind of 60 m.p.h., real speed over the ground would be 270 m.p.h.

The Bottom Line

From 1939 to 1945 Bomber Command lost 8,325 aircraft all told with about 330 others lost on minelaying and secret operations. Of these 2,573 were lost in 1944.

55,573 aircrew, out of a total of approximately 100,000, plus 1,363 male ground staff and 91 WAAFs died while serving with Bomber Command. Of these, 4,050 aircrew were in the RAAF.

Recent Comments