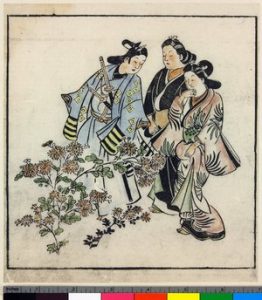

Those familiar with the rich heritage of artwork in Japan will be aware of numerous stories about painted figures which are so life-like that they come alive and step out of their frames, like the characters in Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo. The Kyoto painter Okyo Murayama for instance painted a ghost that was so realistic it floated off from the painting never to be seen again. In ‘The Screen-Maiden’ (part of the miscellany Shadowings, 1900) Lafcadio Hearn writes of a similar phenomenon with regard to the artist Hishigawa Kichibei (aka Moronobu) (1618-94), whose portrait of a young girl captivates a young Kyoto scholar named Tokkei, living in Muromachi Street. Such is the power of his passion that he summons her into existence and ends up happily married to her. As for the painting, “The space that she had occupied upon it remained a blank.” In the piece below, WiK intern Andrew Sokulski uses Hearn’s story as a springboard for reflections upon relationships and the nature of love. (JD)

**********************

Reflections on Hearn’s “The Screen Maiden” by Andrew Sokulski

Oftentimes otherworldly happenings can more precisely explain everyday events in our world. In Lafcadio Hearn’s “The Screen Maiden” an exquisite painting of a beautiful young girl becomes the betrothed of a young man. A most intriguing read indeed, the story seems to hint at three critical aspects of love: patience, humility, and reciprocity.

At the start of the story a description of the miraculous aspects of “Hishigawa’s Portraits” is given. “It is said that the creatures or the persons he painted would separate themselves from the paper or the silk upon which they had been depicted, so that they became, by their own will, really alive.” (Pg. 1) The description makes what would otherwise be seen as absurd into something rational. From this point on, the story tells of how the man and the lady came to be united in love. It starts with him returning home after a day’s work: “One evening, while on his way home after a visit, his attention was attracted by an old single-leaf screen (tsuitaté) exposed for sale before the shop of a dealer in second-hand goods.” (Pg. 2). Intrigued by the portrait, he bought the screen and went home.

After an initial phase of love-at-first-sight, his feelings developed into a more intense relationship. He reached out to her and expressed his amorous feelings. He couldn’t help but think of her day and night, as if her reflection could be seen in the luminous haze of the moon as well as in the radiant glare of the sun. In Hearn’s words: “When he looked again at the screen, in the solitude of his own room, the picture seemed to him much more beautiful than before. Apparently it was a real likeness–the portrait of a girl fifteen or sixteen years old; and every little detail in the painting of the hair, eyes, eyelashes, mouth, had been executed with a delicacy and truth beyond praise.” (Pg. 2). Enraptured by her beauty, the man could not contain his passion, and it seemed the girl too wished to appear to him free of the painting within which she was placed.

Though the man vowed to sacrifice his life if the girl did not become his lover, a friend advised him to be more resolute. Sit before her each day and call her by name, he suggests. Then when she responds, offer her a cup of wine mixed from 100 different wine-shops. Miraculously she does eventually appear, whereupon she acts surprisingly calmly and asks, “Will you not soon get tired of me?” (Pg. 5). He pledges never to leave her and to treat her as kindly as he can. In such humble fashion, their relationship is settled.

Reciprocity is achieved as the two of them come to an agreement to acquiesce in each other’s innermost thoughts. The man overcomes his overzealous emotion in order to have a loving relationship with her. For her part, she agrees to become his partner after making certain that he will not act brashly toward her. It seems they had a smooth relationship: “I suppose that Tokkei was a good boy — for his bride never returned to the screen.”(Pgs. 5-6).

The three aspects of patience, humility, and reciprocity thus enable a crystalized love to be formed. This is underpinned by a play on words, for Hearn mentions the Japanese word 衝立「ついたて」early on in the story, which can be translated as a standing or partitioning screen. In this sense the screen could represent the stages of closeness and distance in love. If one approaches a lover too rapidly, he or she may choose seclusion behind a screen of formalities. If on the other hand one approaches calmly, and if the love is mutual, the couple will come to an understanding of the larger scope of life and a sharing of each other’s stories. Eventually, if their wishes match one another, they may decide to join their circumstances and promise to face the future hand in hand. With love, as with writing, in order to arrive at the point at which one can convey an emotional core to others, one must proceed smoothly, step by step, through screens of understanding and mystery. Only by constant struggle will one achieve calm and clarity in the end. In this way one’s imaginary ideal may well come to life and flourish in actual reality.

*******************

For Andrew’s previous take on a Hearn story, please click here to see his piece on ‘The Sympathy of Benten’.