Leading Shinto scholar Mark Teeuwen, has written several influential books on matters related to Japan’s indigenous faith. He’s known in particular for disputing the idea that there was such a thing as ‘Shinto’ in Japan’s ancient past, but that it was a later construct. His new publication, A Social History of the Ise Shrines, co-written with John Breen, has proved ground-breaking in terms of English language works on the subject. It was a great delight therefore for WiK to host him last Sunday for an informal talk on the changes Ise has been through in its long history.

Leading Shinto scholar Mark Teeuwen, has written several influential books on matters related to Japan’s indigenous faith. He’s known in particular for disputing the idea that there was such a thing as ‘Shinto’ in Japan’s ancient past, but that it was a later construct. His new publication, A Social History of the Ise Shrines, co-written with John Breen, has proved ground-breaking in terms of English language works on the subject. It was a great delight therefore for WiK to host him last Sunday for an informal talk on the changes Ise has been through in its long history.

First some interesting statistics. The Ise complex comprises 125 shrines. There are 120 priests (nearly ten times more than at other major shrines) and 500 auxiliary staff. The shrine owns forests as far away as Kyushu, has four museums as well as offices, educational facilities and residences, in addition to which it hosts facilities to produce rice, salt, timber etc. In short, this is a major enterprise, which moreover is committed to a twenty-year rebuilding cycle estimated to cost 57 billion yen. Small wonder that it needs substantial income, for since the end of World War Two it has been stripped of state support. It comes as little surprise then to learn that the Association of Ise Worshippers is headed by the ex-president of Toyota and that the top ranks are filled with big business magnates.Visitors to Ise may think it’s all about trees and wood, but money is a major concern!

The twenty year rebuilding cycle brings with it renewed focus and a surge of tourism. A comparison of 1993 and 2013 is instructive in this respect. Given that 9 million visitors in 2014 descended on a town of only 130,000, the management of shrine visitors and tourism is a consideration for local residents, and in 1993 much attention was given to a new motorway to the area. At the same time there were protests and even bombs against the imperial trappings and reenforcement of state ties. These were much more evident in 2013, when prime minister Shinzo Abe and eight of his cabinet ministers attended the sengyo no gi rite, in which the sacred mirror of Amaterasu is transferred from the old shrine to the new. The last time a prime minister had attended was in 1929 during the time of State Shinto, yet this won almost no attention in the mass media or from the populace at large. One wonders if it reflects political apathy, or perhaps it is simply an illustration of the drift to the right which has happened under Abe.

A Jinja Honcho campaign to go and worship at Ise

Standard descriptions of Ise like to suggest it has always been supreme and a centre of imperial worship. Mark T. however showed that this was far from the truth, and he identified six major historical periods with quite different values and business models. The shrine dates back to the late seventh century when an angry deity named Amateru (sic) disrupted the imperial household and was ejected, ending up at Ise. Mark T. believes that at this time the deity was male, and that it was only under the influence of Empress Jito (r.686-697) that the deity was feminised by Kojiki mythologisers in her honour (there are parallels between Amaterasu’s son and grandson with those of Jito).

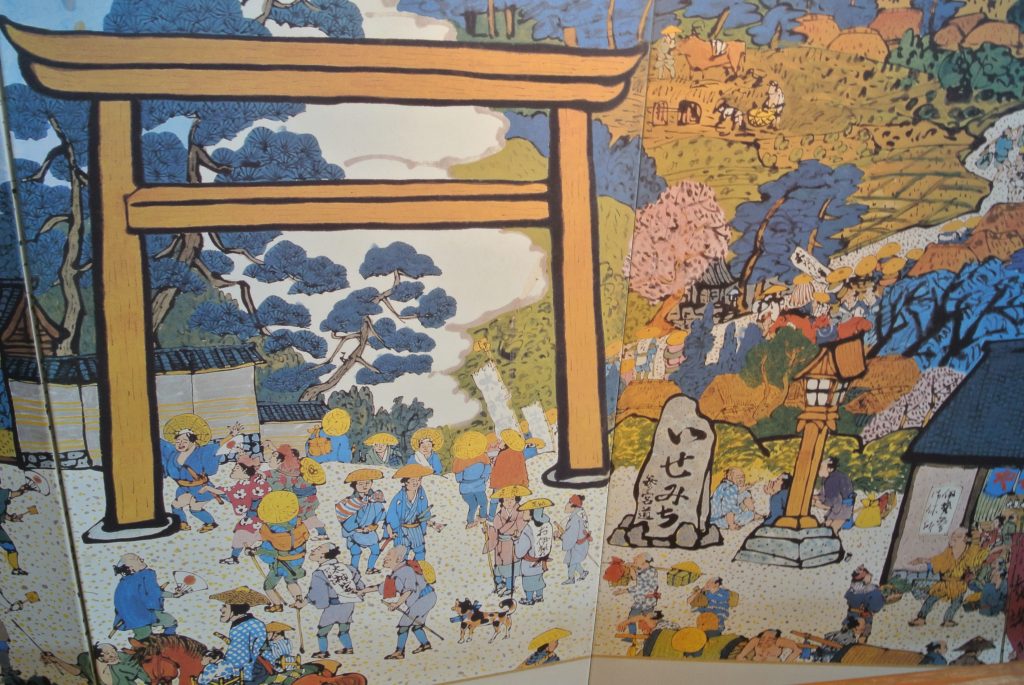

During its subsequent history Ise took many guises. It came as a surprise to learn that at one time it was the seat of Enma, lord of the underworld, and indulgences were sold so as to avoid going to hell. At another time it was closely associated with the samurai (the court made pilgrimages to Kumano instead). Shop councils and inn keepers promoted the pilgrimage business through prayer masters called oshi, and the millions of Edo-era pilgrims who headed for the Outer Shrine were concerned with enjoyment and praying for agricultural success. There was little if any awareness of the emperor at the time, for the Tokugawa were all-powerful (and Ieyasu deified). Only with the development of the Kokugaku movement in the later Edo Period was there a revival in sentiment for the emperor.

It was the Meiji Period which brought major changes to Ise. The era is associated now with ‘the invention of tradition’, and Ise provides a striking example as it was transformed into the ancestral shrine of the emperor and given primacy in religious terms. For a start the oshi business, which had long sustained Ise, was banned. Hereditary priests were ousted and appointees installed. Fences were put up and shrines rearranged in a more rational and imperial manner. The Outer Shrine, for example whose deity was Amenonakanushi, lord of creation, was recast as sanctuary of a food deity serving Amaterasu, In this way the shrine came to take its present form as head of an emperor-centred ideology, and despite the change from nationalised institution to private institution after WW2, essentially nothing has changed. Still today most of the resources of the Association of Shrines (Jinja Honcho) go into supporting Ise’s primacy, even to the extent of using money from poorer shrines (some close to bankrupt).

There is no dogma in Shinto, noted Mark, though Jinja Honcho asserts one dogmatic axiom: Ise is supreme.

In contrast to the solemnity nowadays, Edo-era pilgrims were bent on enjoying themselves and even took a pet dog along, if this officially sanctioned picture is to be believed

Recent Comments