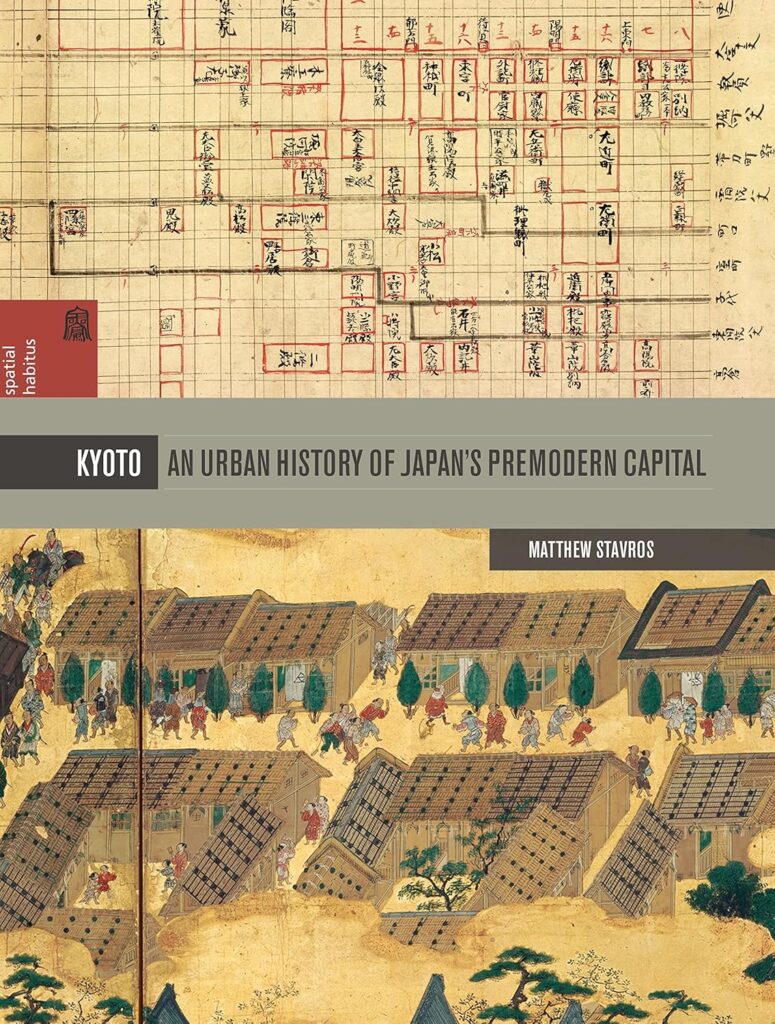

Kyoto: An Urban History of Japan’s Premodern Capital by Matthew Stavros (University of Hawaii Press, 2015)

Book review by Paul Carty, WiK member. This first appeared in the Kyoto Journal.

**************

Kyoto is one of the great centers of culture in the world. We can find many traces of its long history as we explore the ancient capital. Fortunately, we have an excellent new book to help us to read this cityscape, and understand its organization and development. In Kyoto: An Urban History of Japan’s Premodern Capital, Matthew Stavros, a Professor at Sydney University, expertly guides us through the interplay of space and authority. Specifically, how did Kyoto balance its role as imperial capital with being a center of commerce, and later a military headquarters?

The book takes the reader through the first 800 years of the city’s history from the Heian up to the Edo Period, roughly 794 to 1600. In the introduction, Stavros explains that this book is not a comprehensive history of this period. It undertakes to describe the organization and transformations of Kyoto from an imperial city to castle town. The many maps, illustrations and diagrams greatly aid the reader in understanding the dramatic events performed in the urban space. The book is deeply researched and employs primary sources such as letters and diaries to give the reader a great sense of the lived experience of that time. Written in a clear and accessible style, the book covers specific topics with great depth and detail to make larger points on the greater trends that shaped each era.

The first two chapters contrast the ideals of the formation of Heian-kyo with the actual reality. Heian-kyo was established by Emperor Kanmu to support, protect and govern the country. Carefully organized along a grid pattern, Heian-kyo had two market places, a large gate, two temples to the east and west of the gate, and a broad road leading toward the palace. This plan was based on ideas that shaped several Chinese capitals and was meant to reflect the power of the state. Despite this well conceived idea of a capital, the author explains that the residents, both elite and commoners, had their own ideas of how to occupy the space. Most of the original structures of the Heian-kyo slowly disappeared. More importantly, the western part of the original grid was slowly abandoned and the city shifted to the east.

The third and fourth chapters take us into the medieval period where the city develops into two distinct parts, Kamigyo, home to the noble class, and Shimogyo, home to the merchants and a thriving business area. Stavros deftly outlines the profound influence the term rakuchu-rakugai, respectively the inner and outer city, had on the inhabitants of the city. The inner city was roughly from Omiya Street in the west to the Kamo River in the east, Ichijo-ji to the north and Kujo to the south. These were not only geographical terms but also ones that profoundly shaped nobles’ ideas and actions in and about the capital. Basically the imperial court controlled the inner city strictly; therefore, if the elite wanted to build a gorgeous villa complex, they built it outside the inner city during the medieval period.

In the subsequent chapters we learn how the Ashikaga warriors (shoguns from 1333 to 1570) made profound changes to the urban landscape. As the Ashikaga rulers lose power, Kyoto turns into a battleground. After nearly a hundred years of political instability, Oda Nobunaga entered Kyoto (1568) and soon thereafter built Nijo Castle. Stavros explains how Kyoto at this point becomes the prototype of the castle town, which spread throughout Japan. This castle was soon destroyed. Roughly twenty years later (1600) the present day Nijo Castle would be built, but in another location. We can, however, see traces of the first castle in the names of the neighborhoods in that area: Hori no uchi cho means area within the moat.

Hideyoshi follows Nobunaga into power and we learn that he wanted to move the capital to Osaka. Lacking the political and institutional support to control the country, he kept his operation in Kyoto to get imperial and noble support. He followed the traditional route of building important imperial structures in which the ancient rituals could take place. Hideayoshi made the most profound changes to Kyoto including a wall around the city, having most temples moved to a few special locations and the construction of the most fabulous castle and largest Buddhist statue. In chapter seven, Stavros masterfully explains the reasoning behind those changes.

There is also a brief epilogue explaining some major developments during the Edo and Meiji Periods, including Nijo Castle, Takase Canal, and the Imperial Palace.

Anyone with interest in understanding how present day Kyoto took its shape, will be interested in this deeply researched urban history of Kyoto. To those who love Kyoto, this is a great gift.