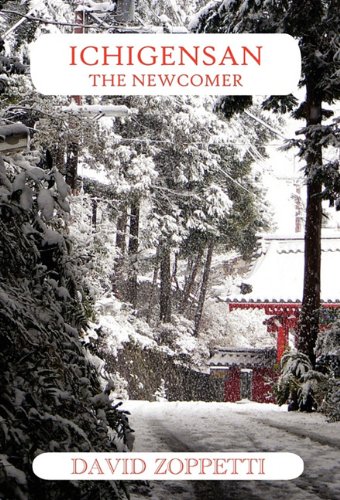

David Zoppetti’s novel Ichigensan was first published in Japanese and won the Subaru Prize for Literature in 1996. Later it was made into a film starring Edward Atterton, and in 2011 the English translation by Takuma Sminkey was published. Set in Kyoto, it concerns an affair between a foreign student of Japanese literature and a blind woman called Kyoko.

***************

Several days later, Kyoko and I were walking up the steep stone steps of the Kibune-jinja shrine, north of Kyoto, in a cold drizzle. Red toro lanterns lined each side of the stairway. As always, I described our surroundings and guided Kyoko’s hand to the wet moss, the massive tree trunks, the stones, and whatever else she wished to touch.

At a kind of viewing platform, we sat down on a bench. Under the same umbrella, we ate the yakiniku lunch that Kyoko had prepared. The arrangement of grilled meat and vegetables reminded me of an abstract modernist painting, but it tasted delicious.

On the train home, Kyoko fell asleep as we were heading towards Demachi-Yanagi, the terminal in Kyoto. I gazed at her sleeping face. I wasn’t thinking of anything particular, when suddenly, it dawned on me why I always felt so at peace with her.

If you thought about it, the explanation was very simple, but it was precisely because it was, that it hadn’t occurred to me for a long time.

She couldn’t see me.

People in Kyoto always stared at me. Their behavior towards someone was always determined by outward appearances, which always made me feel uncomfortable. This is more or less what people do in all countries, but in Kyoto things were somewhat different. The process whereby they looked at someone and based solely on appearance instantly decided something about that person, totally ignoring his or her feelings – to a degree you couldn’t help but admire – was absolutely unique.

This wasn’t a simple matter that could be explained with common words such as ‘discrimination’ or ‘close-mindedness.’ There was a subtle distinction-making mechanism, which at first seemed palpable, but turned out to be invisible and rather creepy. Even if you could feel the mechanism at work physically, it had no clear shape. Whenever I had tried to confront the problem, I had found myself eluded by something I couldn’t define. There was no sound, clash, or pain in the confrontation, but its sheer repetition beat me up both physically and mentally.

And obviously, the source of all this was outward appearances. I guess I was exhausted from always being stared at. I was sick of having to play the role of the gaijin buffoon.

When I was with Kyoko, however, this naturally never occurred. Needless to say, for her outward appearances didn’t exist. From the beginning, our relationship was based on voice, touch, and language – things that bound us beyond outward appearances.

Even if I made a mistake or used an inappropriate turn of phrase, Kyoko focused on the content of what I was trying to communicate. She had transcended nationality and race, and always interacted with me as a fellow human being. That’s how I felt. If Kyoko could see me, our relationship would probably be completely different.

Knowing there was one person in this city that couldn’t see me and could behave in a natural way brought me great peace of mind – more than I could ever express in words. I considered mentioning this to Kyoko, but I feared it might cause some misunderstanding, so I didn’t.

She continued sleeping soundly until the small train reached the final station.