by Rebecca Copeland

Sometimes it’s the unexpected detours that provide the greatest pleasure.

Last week, I spent the afternoon with PhD student Ran Wei, who has been in Osaka on a Japan Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship. We had planned to meet at Kyoto’s Kitano Tenmangu Shrine, tour the garden, and then enjoy a long and luxurious meal discussing her dissertation on Japanese prose fiction set in the city of Osaka.

I checked on the garden schedule, she searched for good restaurants near Kitano Tenmangu and made a reservation at the Sakurai-ya. We arranged to meet at the shrine entrance at 10:30, walk around the garden, and then head to the restaurant by 1:00.

Kitano Tenmangu Shrine June 23, 2023. Credit: Ran Wei

Ran and I met right on schedule and enjoyed working our way through the shrine grounds to the garden. We stopped to rub the noses of the bronze oxen statues and to pay our respects to Tenjin-sama, the God of Learning, his spirit resting augustly in the shrine depths. We both were looking for some divine intervention, Ran for her dissertation, me for my second novel.

It was the season to celebrate the summer maple leaves, ao momiji. We purchased our tickets and entered the garden expectantly.

At every turn we walked deeper and deeper into a tunnel of green—of many greens: emerald, cyan, fern, moss, and malachite. The maple leaves, glistening with the morning dew, were splendid, but they were not alone in their lush glory. Standing in small clumps here and there, tall stalks of bamboo rivaled the maples for attention, the newest shoots were a rich Persian green, nearly teal. A vermillion bridge and ornamental balustrade stood in stark contrast to the greens making both colors all the more vibrant. The graveled pathways were surprisingly unkempt, with vines and brambles stretching out to snatch at passersby, who were few—a small blessing in the normally crowded Kyoto. We agreed that the tangled atmosphere of the garden only enhanced its charm.

Vermillion Balustrade. Credit: Rebecca Copeland

After we had bathed in the eddies of green for what felt an extraordinary amount of time, we emerged to discover we still had nearly two hours before our lunch reservations.

We decided to stroll to my lodgings in the middle of the Nishijin area, famous for its production of exquisite brocades. Occasionally when I walk through the streets on this or that errand, I’ll hear the sounds of weaving, the click, clack of the looms, the soft thud of the shuttle.

“What’s this?” Ran asked, pointing to a sign on an old machiya row house we were passing. It read in English:

Soushitsuzure-en

Textile Studio

Off to the side another sign announced in Japanese kengaku, which means “observation” but literally reads “look and learn.”

“Let’s try?” Ran suggested.

We followed a long, covered walkway that opened into a sunny courtyard. We were not sure what to expect. We noticed another kengaku sign and followed it to what looked like the door to the studio.

We rang the bell and within minutes a young woman appeared. When we asked if we might kengaku, she pulled two pairs of slippers from the shelf to her left and placed them on the floor before us.

We stepped out of our shoes and entered a very cluttered space full of seven or more looms, walls of thread, and lots of papers with illustrations stacked upon almost every flat surface.

“Irrasshai.”

A thin, bespectacled elderly man with kind eyes emerged from one of the looms to greet us. The young woman disappeared. The man introduced himself as Mr. Hirano.

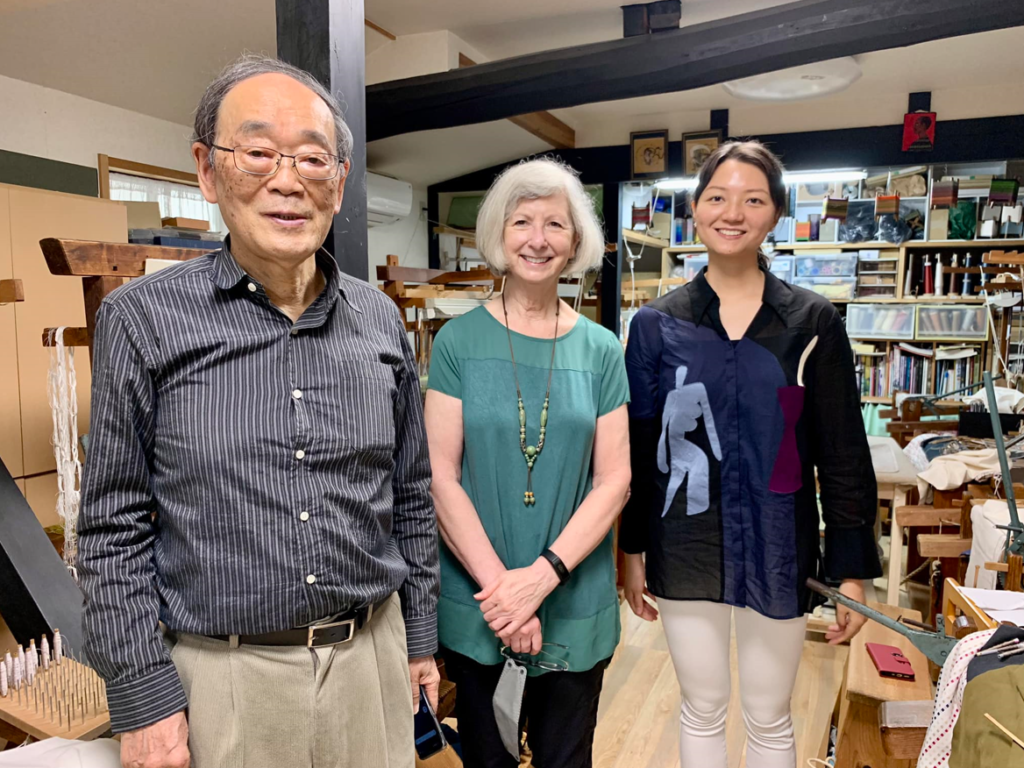

Image of Mr. Hirano, Rebecca Copeland, Ran Wei

For the next hour Mr. Hirano told us about the weaving process. He showed us a short video narrated in English that explained each step. Mr. Hirano stopped the video regularly to explain the processes himself, in Japanese, elaborating and allowing us to ask questions.

We watched the way the weaver prepares the loom, first selecting the thread, twisting two different colors of threads together to make elaborate hues, spinning the thread onto spools, different spools for different colors. It can take weeks just to load the thread, depending on the pattern to be woven.

Mr. Hirano, we learned was born into a weaving family.

“I’ve been weaving for 70 years,” he told us.

Later, when we learned he was 78, we imagined him as an eight-year-old boy twisting threads onto spools.

“It takes at least 40 years before you’re really a full-fledged weaver.”

Ran turned to me and quipped with a smile, “I guess writing a dissertation isn’t as bad as I thought!”

When the video ended, Mr. Hirano spread a beautiful museum catalogue before us and pointed to the photograph of an elegant Buddhist figure. We thought it was a painting until he revealed it was Nishijin brocade. He had led a team of six weavers, all over the age of 50, in the project. It took them over three years to complete the weaving, which unfurled at over three by six feet. The piece is now in a museum in Shiga Prefecture.

“We keep these covered, you know,” Mr. Hirano explained as he led us to a wall of spooled and bundled threads. He turned on the overhead light, allowing us to appreciate the amazing array of hues.

Image of threads: Credit: Rebecca Copeland

“Excessive light can fade the dyes.”

Next, Mr. Hirano showed us the piece he was currently working on and the way the weaving is done “backwards,” that is to say, the front of the piece is face down as the weaver works the loom. They need to carry a mirror to check the underside of the loom.

Tall but limber, Ran crouched down under the loom to photograph the underside, then held her camera out for me to see.

So much of the craft is done by instinct and inspiration.

“Tsuzure-ori,” he explained, “is the oldest of the Nishijin weaves. Weavers use their bodies in harmony with the loom—their feet to move the heddle, their hands to set the loom and pull the shuttle, and especially their fingernails to slide the threads tightly in place. Nowadays so much of this weaving is done by machine, so this studio was founded to help preserve the old techniques.”

Image of workspace with papers and looms. Credit: Rebecca Copeland

In addition to the young woman we met at the door—who retired to a corner of the studio to work on a computer, perhaps keeping the accounts—there was only one other person in the studio, a woman working quietly at her loom in the other corner.

“We cater to local artists and to people who weave as a hobby.”

Aside from the large museum piece, most of the other items Mr. Hirano showed us were small.

“Hardly anyone orders obi sashes and kimonos anymore,” Mr. Hirano explained. These had been the mainstay of the Nishijin industry. A few businesses still produce the sumptuous robes used on the Noh stage, but smaller operations like Mr. Hirano’s have had to become more industrious to stay in business.

Not that Mr. Hirano was much in business anymore. His interests now were mainly in preserving the art form.

For a small fee, visitors could make their own accessory: a lampshade, a coaster, or a small item like a keyring.

We decided not to. Our restaurant awaited us.

But we did purchase a small piece of jewelry each, to commemorate our visit, and took a few photos with Mr. Hirano.

We thanked Mr. Hirano, slipped into our shoes, and off we went to our lunch reservations.

Over a delicious meal of seasonal vegetables and fish we reflected on what we had learned—Mr. Hirano’s patience, his focus and diligence. Good lessons for both of us as we face down our various writing projects.

Our impromptu kengaku was the high point of our very wonderful Kitano Tenmangu adventure. Tenjin-sama clearly heard our prayers.

Image of Author and Ran Wei enjoying lunch at Sakurai-ya, June 23, 2023.

Credit: Sakurai-ya staff member using Ran Wei’s phone.

* * * *

Rebecca Copeland is a writer of fiction and literary criticism and a translator of Japanese literature. Her stories travel between Japan and the American South and touch on questions of identity, belonging, and self-discovery. Her academic writings have focused almost exclusively on modern Japanese women writers, and she has translated the works of writer Uno Chiyo and novelist Kirino Natsuo. Copeland was born to missionary parents in a Japan still recovering from the aftermath of war. As a junior in college, Copeland had the opportunity to spend a year in Japan, where she studied traditional dance, learned to wear a kimono, and traveled. Afterwards she earned a PhD in Japanese literature at Columbia University, and she is now a professor at Washington University in St. Louis. The present work, The Kimono Tattoo, is her debut work of fiction. More information may be found on her website, rebecca-copeland.com.

Recent Comments